Arthur Rubinstein with Piano Music by

Stravinsky / Scriabin / Mompou / Rubinstein / Gershwin

Media Review / Listening Diary 2014-05-07

2014-05-07 — Original posting (on Blogger)

2014-11-12 — Re-posting as is (WordPress)

2016-07-21 — Brushed up for better readability

Table of Contents

Exploring the Fringes of Rubinstein’s Recording Repertoire…

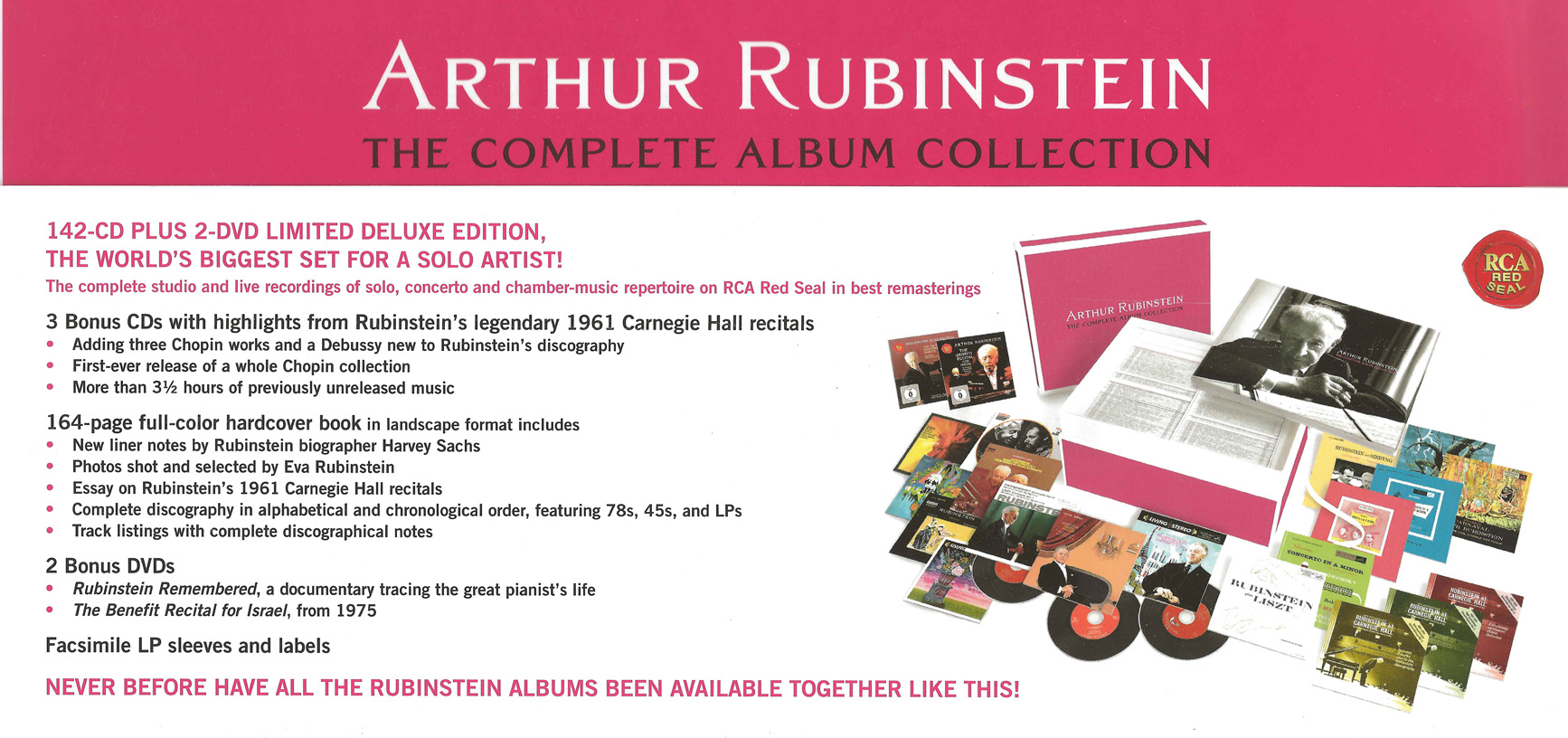

This posting is about compositions by Stravinsky, Scriabin, Mompou, Anton Rubinstein and Gershwin. It’s another, very small portion in Arthur Rubinstein’s recording history, more accidental than systematic, included in the recently released “Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection“:

Piano Music by Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971)

The CDs

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CD #140

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CD #140: New Highlights from Rubinstein at Carnegie Hall, from 10 historic recitals, 1961

Compositions by Debussy, Albéniz, de Falla, Granados, Liszt, Scriabin, and Stravinsky

Arthur Rubinstein

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., track listing on CD sleeve

Maurizio Pollini

Stravinsky: Pétrouchka; Prokofiev: Sonata No.7; Webern: Variations op.27; Boulez: 12th Sonata

DG 447 431-2 (CD, stereo); ℗ 1972/78 / © 1995

The Composition

Stravinsky completed the “Trois Movements de Pétrouchka” in 1921. The composition is not meant to be a transcription, but merely a composition based on themes / material from the ballet “Pétrouchka”. Stravinsky dedicated it to his friend Arthur Rubinstein. He apparently wanted to make the three movements musically appealing and yet technically challenging. He certainly achieved that latter point, as these movements are extremely difficult to play. Rubinstein performed the composition in concerts, but he never made an official recording. However, we do have a recording with Rubinstein playing this piece in a concert at Carnegie Hall, in 1961 (first CD shown above).

I do have another CD with the “Trois Movements de Pétrouchka“, played by Maurizio Pollini (1942 – 2024), who recorded this in 1971, at the top of his technical abilities. I think the recording (second CD shown above) is one of Pollini’s top highlights from that time.

The three movements from “Petrushka” for piano consist of

- Danse russe (Russian Dance) — ca. 2.5′

- Chez Pétrouchka (Petrushka’s Room) — ca. 4′

- La semaine grasse (The Shrovetide Fair) — ca. 8′

Comparing Recordings

In a first round, I was comparing the above two recordings, and especially in the first movement it seemed hared to believe that the two artists are playing the same music! Rubinstein always pointed out that he sincerely tries being a faithful mediator to the music of a (any) composer (which is also why he refused to record early classical or baroque music) so I assume he was playing what he had in his score, hence I believe that Rubinstein must have been playing a different version of this piece (and be it only for the added bass tremoli at the end of the first two movements).

To verify this, I checked a number of recordings on YouTube. The artists that I heard & watched all play the score that Maurizio Pollini is playing. Here are some quick, personal remarks on several recordings:

Alexis Weissenberg

An older YouTube recording (based on a film recording) with Alexis Weissenberg (1929 – 2012): extremely virtuosic, fast, unfortunately with limited sound quality (and mono only), and with an odd cut within the third movement; overall, it’s a bit breathless, pushed, as if there was a deadline, sometimes almost machine-like, obsessed (an aspect that is in Stravinsky’s music, too, but not exclusively). The interpretation lacks the time for poetic moments, but still it is fascinating to watch!

2’18” / 3’22” / 7’12”

Michel Béroff

A YouTube recording (score tracking) with Michel Béroff (*1950): Most interesting for the score tracking (in case you don’t have a score at hand), stereo, but also with limitations in the sound quality. It lacks transparency: sometimes it sounds as if the recording had been done with two pianos, or two consecutive recordings mixed together. I’m not suggesting anything here, I’m just reporting what I sense from listening to the audio track. The artist’s performance is not bad overall, but does not reach Weissenberg’s virtuosity, nor Pollini’s transparency & clarity, nor Yuja Wang’s expressivity. Also, sometimes it is slightly lacking the ultimate precision and conciseness, occasionally losing the drive / flow.

2’27” / 4’22” / 8’27”

Yuja Wang

A recent live recording (YouTube, from the Verbier Festival, probably 2012) with Yuja Wang (*1987): Yuja’s technical skills, the power, flexibility and precision in her hands & fingers are astounding. But even more amazing is how she uses her talents in this music! The piece is never mechanic, nor does she turn out the super virtuoso (like Weissenberg). Instead, the music is joy- and playful, she enjoys the jazzy aspects, and — most important — she adds emotion, expression, through agogics, and she leaves time to listen into the pieces, and she pays attention to secondary voices and melodies.

It’s a live performance, so not everything is perfect, polished, and the sound could be a little better, too. But it remains a very impressive performance, nevertheless. To my feeling, the one minor thing to criticize may be that the musical flow in the third movement (which definitely is not intended to be as mechanic as with Weissenberg!) is perhaps slightly less harmonic than with other pianists, such as Maurizio Pollini.

2’28” / 4’20” / 8’27”

Maurizio Pollini

The above CD, recorded 1971, with Maurizio Pollini (1942 – 2024): It may be a bit unfair to compare a studio recording with live performances. Clearly, this recording has the best sound of all those discussed. Of course, I can only compare what I have at hand. To me, this still is the reference recording for these three movements (as well as for other pieces on that CD). His technique, his playing are perfect, appear absolutely effortless, his rhythmic precision and agility, the transparency and clarity are unmatched, his dynamics are differentiated, and he maintains a compelling musical flow, without ever being mechanic like Weissenberg.

The one area where I think Yuja Wang beats him is in expressiveness and emotionality. Though I would by no means want to claim that Pollini’s interpretation is cold or sterile: it’s just that he takes a more “objective” approach.

2’32” / 4’17” / 8’35”

Arthur Rubinstein

Finally, Arthur Rubinstein‘s live recording from Carnegie Hall, 1961 (the first CD above): let me start with stating that I have yet to hear another pianist who can still play this composition at the age of 74 — and with that much power! Unfortunately, that’s about the one positive thing that I can mention here. Maybe the microphone was vastly overdriven, but for the most part (with the exception of a few p passages, especially in the second movement), Rubinstein’s performance appears to be fff … fffff, driving the concert grand to its limits. The musical flow is best in the third movement, in the first movement there are some odd tempo changes.

I have the impression that Rubinstein was playing a different version than the other pianists mentioned here, see also the note above. Yes, there are extremely virtuosic passages, but I have a hard time enjoying these here. Overall, I sense that Rubinstein’s performance follows a tradition similar to Weissenberg’s (although he never really is as mechanic or obsessive). But Stravinsky’s music is more than that, I think.

2’38” / 4’11” / 7’42”

Conclusion

Clearly, my favorites here are Yuja Wang and Maurizio Pollini.

Piano Music by Alexander Scriabin (1872 – 1915)

The above live recording from Carnegie Hall (1961) contains a rare gem: Rubinstein’s only recorded piece by Alexander Scriabin, the Nocturne in D♭ major for the left hand, from Scriabin’s “Prélude and Nocturne for the left hand”, op.9. The piece lasts 4’15” (without Rubinstein’s encore announcement and the applause). It’s a very nice piece, indeed! It’s a piece somehow in line with Godowsky’s famous Studies on Chopin’s Etudes (where 22 out of 54 Studies are for the left hand alone), certainly difficult to play, though not quite with Godowsky’s extreme technical demands. Still, it’s astounding what a pianist’s left hand can do: fascinating, and the public seems to like it!

I don’t know how much Scriabin Rubinstein played in his life. The fact that this is the only recorded piece, and that it is not from a regular recording, indicates that Rubinstein probably felt that he was not in a position to deliver an authoritative interpretation of Scriabin’s oeuvre that he would approve of for a “real” recording. This is probably more a matter of familiarity with that music, rather than Rubinstein not being able to play these compositions. In any case, that’s all the Scriabin that we appear to have from Rubinstein’s hand(s)!

Piano Music by Federico Mompou (1893 – 1987)

The CDs

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CD #55

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CD #55: Falla: Nights in the Gardens of Spain; music of Granados, Albéniz, Falla, Mompou

Arthur Rubinstein

Enrique Jorda, San Francisco Symphony Orchestra

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp.; LP liner notes on back of CD sleeve

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CDs #134/135

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CDs #134/#135: Arthur Rubinstein — Unreleased Recordings

Music by Saint-Saëns, Debussy, Granados, Albéniz, Schumann, Anton Rubinstein, Mompou, Chopin, and Schubert

Arthur Rubinstein

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., track listing on CD sleeve

About the Composer

Federico Mompou i Dencausse (1893 – 1987) was a Catalan composer who spent parts of his life in Paris and was well-known in that town in the early 20th century; most of his oeuvre consists of piano miniatures and of songs. It is largely forgotten today. In his officially released discography, Rubinstein recorded one such miniature (No.1) from a collection of 15 (on the CD #55 above, “Falla: Nights in the Gardens of Spain”), which were published under the title “Cançons i Danses” — short pieces consisting of a slow, introductory Cançó (Song), followed by a Dansa (Dance). The “Complete Album Collection” includes another example (No.6), under “Unreleased Recordings”, shown above.

What Rubinstein Selected

The two pieces are

- F♯ major: Cançó: Quasi moderato (based on La hija de Crimson) — Dansa: Allegro non troppo (based on Dansa de Castelltercol) [3’58”]

- E♭ minor: Cançó: Cantabile espressivo — Dansa: Ritmado [3’13”]

Both pieces are typical encores, which is likely how the first piece found its way onto the CD with Manuel de Falla’s “Noches en los Jardines de España“. The second one (#6) was even dedicated to Arthur Rubinstein by the composer, but strangely got never officially released as a recording in his lifetime. Maybe because the piano tone in this track is a bit harsh? Apparently, this #6 was one of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli’s favorite encores: a nice piece with its Latin American rhythms! Not very heavy music, of course, but well played by Rubinstein, and the piano sound limitations really aren’t a major concern here!

Piano Music by Anton Rubinstein (1829 – 1894)

The CD

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CDs #6 – 10

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CDs #6 – 10: The Early Recordings 1931 – 1939

Arthur Rubinstein

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., track listing on CD sleeve

About the Composer

Arthur Rubinstein would never have played music by Tchaikovsky’s friend and mentor Nikolai Rubinstein (1835 – 1881); up to his late years he was still utterly upset by Nikolai’s initial, harsh rejection of Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto in B♭ minor, even though Nikolai later changed his mind, performed it in Paris and helped making that composition the huge success that it later became (and remained, to this very day). Nikolai did not compose much music (and some claim it to be “irrelevant”).

However, Nikolai’s brother Anton Rubinstein (1829 – 1894) was an (almost?) equally good pianist and a prolific composer, and Arthur Rubinstein occasionally played a very small selection of his oeuvre.

Rubinstein’s Repertoire Selection

Most of what still remains of this in recordings falls under “Unreleased Recordings” and is included in the corresponding 2-CD subset “Arthur Rubinstein — Unreleased Recordings” above (under “Piano Music by Federico Mompou”), all recorded in 1953 (mono, of course), plus one track that was recorded back in 1935, for 78’s:

- Valse-Caprice in E♭ major (Vivace):

- early recording from 1935: duration 4’11”

- recording from 1953: duration 5’11”

- Barcarolle No.3 in G minor from “6 Pièces caractéristiques for 4 hands“, op.50, in a version for two hands (by the composer), recorded 1953: duration 3’47”

- Barcarolle No.4 in G major (Allegretto con moto), recorded 1953: duration 4’19”

Barcarolle No.4

This is a rather harmless piece, an encore at best. It’s well played, but not something one would (probably) listen to very often.

Barcarolle No.3

That’s a different “beast”: originally written for four hands, here played in the composer’s own reduction for two hands. Harmonically it may be harmless, but even in this version the piece features some of the inherent complexity of a piece for four hands, while retaining the calm, swinging character of a Barcarolle, not trying to impress with virtuosity — I like this much more than No.4.

Valse-Caprice in E♭ major

The Valse-Caprice in E♭ major is a lively waltz, like some of the Strauss family, but for the piano, and fairly virtuosic. It’s a nice, entertaining, short piece, ideal as encore. Arthur Rubinstein recorded this “officially” a first time, back in 1935 (aged 48): swinging, joyful, often boisterous music — with focus on the entertainment value, so to say.

In 1953 he took another go at this piece, maybe with the idea to provide a more thoughtful, more detailed / careful, less “superficial” interpretation? Though I would not call the early recording superficial — Arthur Rubinstein’s playing is perfectly adequate for that piece, I think. Maybe he also meant to be more faithful towards the composer? That second recording is substantially slower than the first one, and indeed more careful and detailed: all scales are played out clearly, the entire piece is played with high virtuosity. It may indeed be a closer representation of the score, however, that version also loses some of the drive, the swing and joy of the earlier recording. Yes, the playing is more impressive, the clarity and virtuosity are astounding. But overall I like the older recording just as much!

Maybe it’s because of the upcoming stereo technique that these pieces were never released, or the artist somehow changed his mind / view? We don’t know: in the interviews in the Album Collection, he states that he would typically not stop a recording session until the recording represented the (momentarily) best, most appropriate performance. But invariably, after a year or so, he would find that his interpretation / opinion had moved on; and so, there may have been delays in the production, up to a point where he could no longer stand behind these unreleased recordings?

Piano Music by George Gershwin (1898 – 1937)

The CD

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CD #11 – 14

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CDs #11 – 14: The Early Recordings 1938 – 1949

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., track listing on CD sleeve

Comments

I’m not a huge fan of George Gershwin’s music in general. But this piece, the Prelude No.2 (Andante con moto, duration 3’29”), an encore that Rubinstein recorded back in 1946 (the one and only Gershwin in this entire collection), is indeed a nice, melancholic little composition. The sound is mono, but perfectly OK (consider its age of nearly 70 years!). Apparently, Rubinstein did not feel a need to re-record this with newer technique. I can see that the mono recording is perfectly adequate for capturing the essence of this calm, slow piece. Maybe Rubinstein stopped playing it in his later years?

Listening Diary Posts, Overview