Arthur Rubinstein—”The Complete Album Collection”

Media Overview

2014-04-27 — Original posting (on Blogger)

2014-05-03 — Started listing related blog posts (addendum)

2014-05-10 — Added table of related blog posts by CD number (addendum)

2014-11-12 — Re-posting (WordPress), addendum moved into a separate page

2016-07-20 — Brushed up for better readability

2019-01-20 — Correction of an error pointed out by Alex Leach (thanks for the note!)

Table of Contents

Introduction

As mentioned in my Listening Diary 2014-04-13, I have recently received the “Arthur Rubinstein, The Complete Album Collection“. This was a generous gift from colleagues in my former job:

General Observations

First, some general observations:

- As mentioned in my previous post, the album collection uses the original “packaging”. Except for the unreleased recordings and the tracks that were transferred from 78’s, the CDs are meant to be LP replicas. Rubinstein did of course not produce “genuine” CDs. The sleeves are replicas of the original LP sleeves. So, rather than featuring the typical 70 minutes of music per CD as in new releases, the CDs in this collection feature an average duration of around 46.5 minutes, a total of 110 hours overall.

- The two DVDs in the package are not accounted for in the analysis below. One of these features the live recording of Rubinstein’s Benefit Recital for Israel, in 1975, which is also included on the CDs #136 and 137.

- CD #139 has no music, but three interviews (73’40”). This was also excluded from the analysis below.

- One single recording (Beethoven’s piano sonata #18 in E♭ major, op.31/3, “The Hunt”, recorded 1976-04-21:23) is present on two CDs. On the original LPs these were likely identical. Here, the two instances were created from two different “matrices”. The durations are exactly identical, the sound in the second one may be a tad brighter, clearer. In any case, only one instance of this recording was accounted for in the analysis below. The two CDs are

- #125 (along with Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestücke op.12), probably from the original tapes, and

- #133 (together with Beethoven’s piano concerto in B♭ major, op.18, with Daniel Barenboim conducting), probably from the LP.

Statistical Views on Arthur Rubinstein’s Recordings

I have given a brief content overview in the Listening Diary 2014-04-13. In the meantime, I have “ripped” all 142 audio CDs. This way, I can enjoy their contents more systematically, rather than just picking individual CDs for casual listening. For example: with all tracks in my computer, I can easily pick all recordings of a given piece and play them along with recordings by other artists in my collection. Plus, with contents of these 142 CDs now at my fingertips, I can try getting an idea about Arthur Rubinstein’s recording repertoire, his preferences and (deliberate) limitations / restrictions, as in this post.

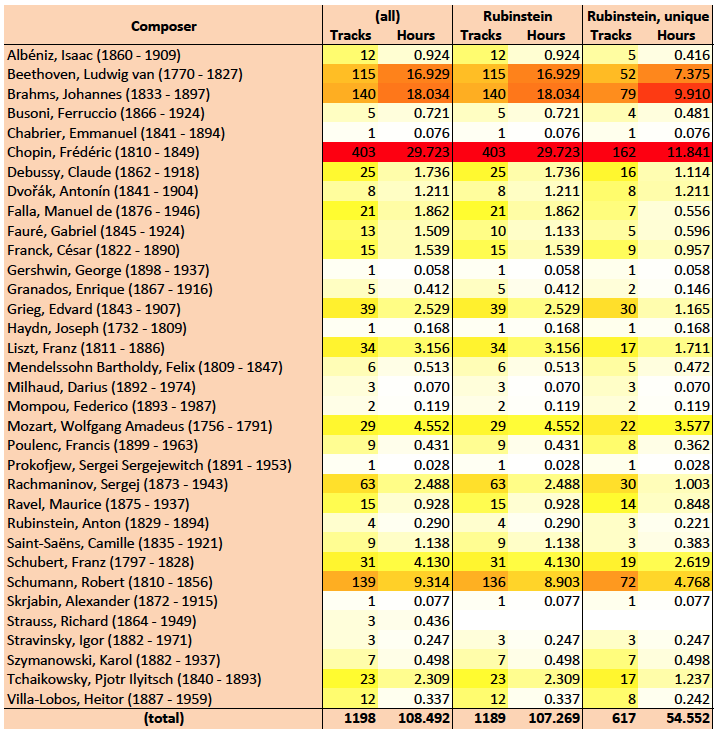

Contents by Composer, Alphabetic

So, what’s in the box in terms of music (tracks, duration) per composer?

I have used cell coloring to indicate dominating composers. The coloring (white = 0 -> yellow -> red = maximum value) tries to imitate a logarithmic scale, such as to retain some color differentiation also at the bottom end.

Explanations on the Table Columns

“(all)”

The columns labeled “(all)” reflect the complete Album Collection. The original LPs featured three recordings (9 tracks) with compositions played by artists not including Arthur Rubinstein, including

- Schumann’s Cello Concerto played by Gregor Piatigorsky (CD #45, featuring also Brahms’ cello sonata #1, op.38, with Rubinstein & Piatigorsky),

- Richard Strauss’ violin sonata played by Jasha Haifetz and Arpád Sándor (CD #46, featuring also the Franck violin sonata, with Rubinstein & Haifetz),

- Fauré’s string quartet op.121 played by the Guarneri String Quartet (CD #121, featuring also Fauré’s piano quartet #1, op.15, with Rubinstein & members of the Guarneri String Quartet)

“Rubinstein”

The columns “Rubinstein” exclude these 9 tracks not featuring Arthur Rubinstein.

“Rubinstein, unique”

The columns “Rubinstein, unique” only accounts for a single recording per composition. Some composition were recorded up to five times between 1928 and 1976 (e.g., Beethoven’s piano concertos). In terms of duration and number of tracks, this shows that about half of the recording time is spent on re-recordings of Rubinstein’s favorite compositions. The timing in these columns is approximate, as the durations changed over all these years. I do not suggest that only one (e.g., the earliest, or the latest one) out of several recordings ought to be considered worth listening to — quite to the contrary:

- These repeat recordings show how Rubinstein’s interpretation evolved over the years.

- These also are Rubinstein’s all-time favorites, music where he was most critical about his recordings. In the interviews, he mentions that to him, the biggest deficiency of any recording is that it freezes a given interpretation, while his view of a given piece continues to evolve over the years.

- Within such a recording series, one can often not declare any given instance “the best”. The early recordings may indicate the artist’s (relative) youth. The last recordings likely show a more mature, more reflected view, but may also indicate technical limitations due to the artist’s age.

What Can we Take from This?

What does the above table tell us, then?

- Not unexpectedly, Rubinstein’s repertoire focuses on Chopin, a composer that he felt a “natural affinity” for, and of which he recorded a very wide range of compositions. Note that even with Chopin, he did not try providing complete coverage. He recorded all Mazurkas, Préludes, Scherzi, Nocturnes and Polonaises, but only very few of the Etudes op.10 and op.25.

- Next is Brahms, with fairly good coverage,

- followed by Beethoven (the five piano concertos, all several times, but only 7 out of 32 piano sonatas, the trio op.97, and 3 of the 10 sonatas for piano and violin),

- then Schumann (with already fairly spotty coverage).

- These four composers already account for over 60% of the unique compositions, or almost 70% of the total recordings (time & tracks) in this collection.

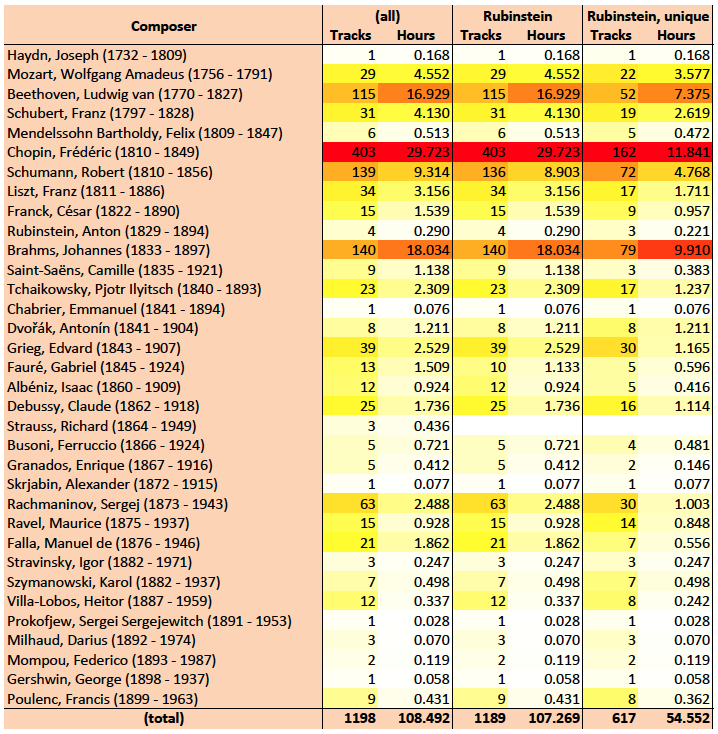

Contents by Composer, Chronologic

The picture gets even clearer if we sort the composers chronologically (by birth date):

Conclusions from the Chronologic View

- In his recordings, Rubinstein clearly focused on the late classical and early romantic periods. There is almost no Haydn, select Mozart only (5 out of 27 piano concertos, two piano quartets, the Rondo K.511), select Beethoven, some Schubert, good coverage of Chopin (whom he regarded a classical rather than a romantic composer!), Schumann and Brahms (both in some ways still with close ties to the classical period);

- there is limited focus on Grieg (mainly four recordings of the piano concerto) and Rachmaninoff (3 recordings of the piano concerto #2, two recordings of the Rhapsody op.43);

- the rest can essentially be summarized as a broad, but limited, spotty selection of pieces by Spanish and French composers.

- The highly virtuosic repertoire by composers such as Prokofiev, Scriabin is virtually absent, as is any music from the early and pre-classical periods, and

- also coverage of music from the 20th century is rather thin.

- Relative to Chopin and Beethoven, Brahms has a stronger focus among the “unique recordings” than in the entire collection. With the former two composers there are proportionally more repeat recordings.

Final Notes

Important: in the collection, only 8 out of 141 CDs (with music) are live concert recordings (#78, #131, #136 – #138, #140 – #142). The collection essentially reflects Rubinstein’s recording repertoire only. The artist only recorded compositions where he felt that he was able to reproduce the composer’s intent. There is

- no original Bach (“the composer did not know the piano as an instrument”),

- very limited Mozart and virtually no Haydn (“the piano was in very early stages of its development during the lifetime of these composers”), and

- with other compositions he probably felt that he was not in a position to produce a rendition that is worth preserving for the future. It must be for this reason that with Stravinsky’s Trois mouvements de “Pétrouchka” (which the composer wrote upon suggestion by Arthur Rubinstein), there is a live recording from 1961, but no studio recording from earlier years.

His concert repertoire must have been substantially wider than the one he recorded.

All this is not meant to be rating comment. I’m just trying to illustrate “what’s in the box”, and, in fact, I’m looking forward to exploring all this music over the coming months and years!

Links, Related Posts

Relating blog posts to compositions and CD numbers in the above collection

You’re missing some Bach that Rubenstein recorded. The Chaconne and the Toccata, Adagio and Fugue arranged by Busoni.

Hi Regel, thanks for your comment. No, I did not miss these — it’s just that I listed them under “Busoni”. Under “Final Notes” I explicitly mention “no original Bach” (along with Rubinstein’s own argumentation), and I have briefly discussed the exact pieces you mention in a separate post.