Arthur Rubinstein playing Piano Music by

Franz Joseph Haydn & Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Media Review / Listening Diary 2014-05-09

2014-05-09 — Original posting (on Blogger)

2014-11-12 — Re-posting as is (WordPress)

2016-07-21 — Brushed up for better readability

Table of Contents

Exploring the Fringes of Rubinstein’s Recording Repertoire…

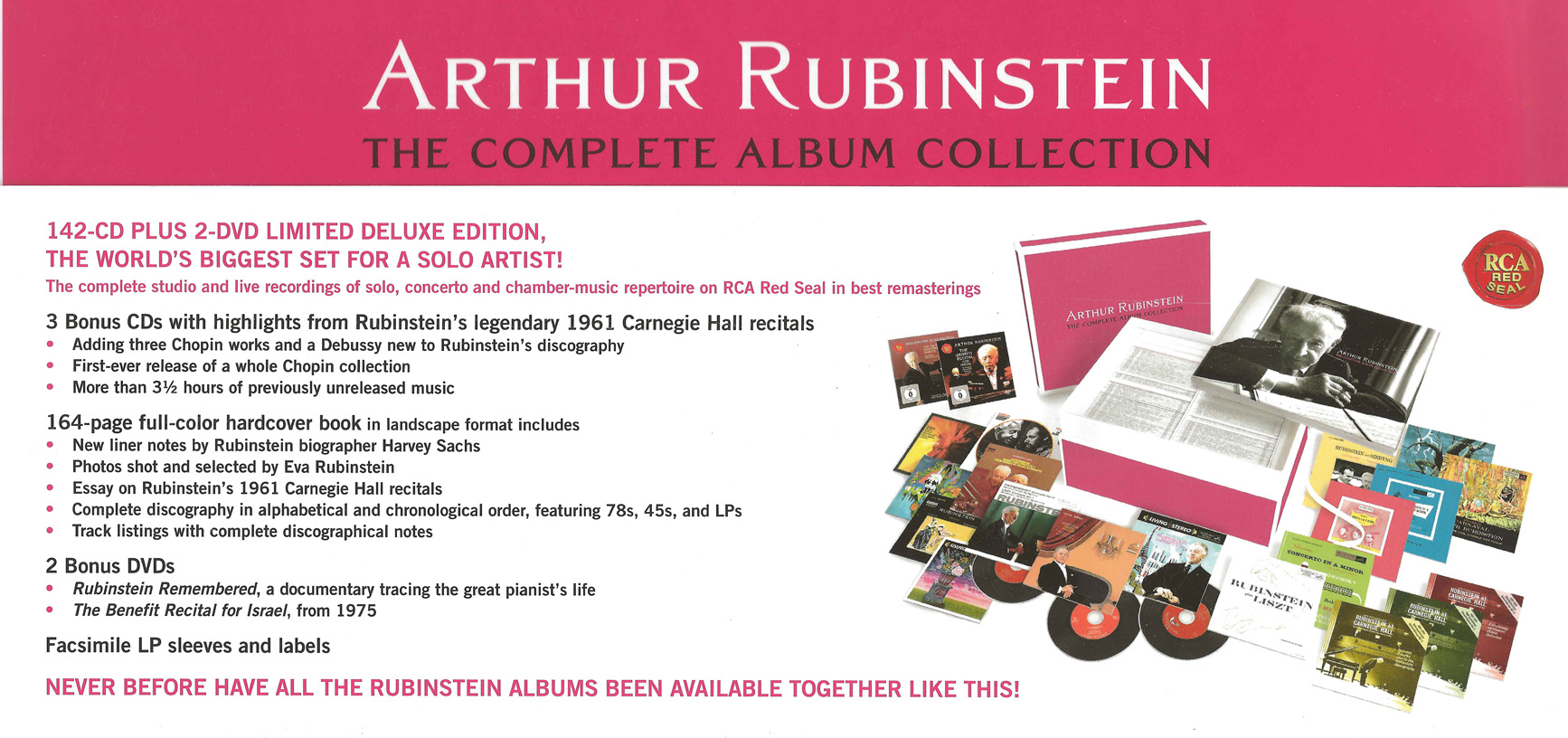

This posting is about compositions by Haydn and Mendelssohn Bartholdy. It’s another, very small portion in Arthur Rubinstein’s recording history, more accidental than systematic, included in the recently released “Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection“:

Piano Music by Franz Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809)

The CDs

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CD #85

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CD #85: Mozart: Concerto No.20 in D minor, K.466; Haydn: Andante con Variazioni

Arthur Rubinstein

Alfred Wallenstein, RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., Information on Mozart concerto on back of CD sleeve

Rudolf Buchbinder

Haydn: Complete Piano Sonatas

Warner Classics 2564 63782-2 (10 CDs, stereo); ℗ 1974/75 / © 2006

Booklet 31 pp., e/f/d

Christine Schornsheim

Haydn: Die Klaviersonaten / Piano Sonatas

Capriccio 49 404 (14 CDs, stereo); © 2005

Booklet 79 pp., d/e/f

Andreas Staier

Haydn: Piano Sonatas and Variations

deutsche harmonia mundi 82876 67376-2 (3 CDs, stereo); ℗ 1990/1993 / © 2005

Booklet 20 pp., d/e/f

Andante con Variazioni in F minor, Hob.XVII:6

Arthur Rubinstein recorded one single composition by Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809), the Andante con Variazioni in F minor, Hob.XVII:6, also titled “Un piccolo divertimento“. Why only one composition by Haydn? Rubinstein explicitly refers to this in interviews. He felt that Haydn only encountered early stages of the piano and couldn’t have an idea of the modern concert grand played today. The artist would have played more Haydn if he had been playing the harpsichord or the fortepiano, which he didn’t, nor ever aspired to. Rubinstein left this music to the specialists for that period. The same he did with the music by Bach and all other baroque composers. Even Mozart’s music largely fell under that spell.

About the composition:

The “Andante con Variazioni” was composed in 1793. It isn’t just a little, casual composition as the subtitle suggests, but a mature, thoughtful, emotional composition, anything but superficial, and fairly virtuosic. In that sense, Rubinstein’s selection certainly was a careful, conscious one!

This is actually a set of double variations:

- A first theme in F minor (Andante) in two parts (2/4, 12 + 17 bars), each repeated (AABB)

- A second theme (Trio) in F major, again in two parts (10 + 10 bars) and each part repeated (CCDD)

- Variation I with the same structure, number of bars, and tonality (AABB-CCDD)

- Variation II — like variation I, but more virtuosic, the Trio (F major) part is altered to 8 + 11 bars)

- A free Coda (“Finale“, 82 bars) without repetition marks.

No tempo annotations are present after the initial Andante.

About the Recordings / Interpretations:

It may seem unfair to compare interpretations on a modern concert grand with historically informed recordings using a period instrument (or a replica thereof). However, I think this is still justified here. The metronome numbers reported below were determined (estimated) during the initial Andante.

Arthur Rubinstein (1960):

1/4 = 44 (Andante) / 1/4 = 50 (Trio); duration: 10’55”

Instrument: Steinway

Unfortunately, Rubinstein does not play any of the repeats. But that is my only (minor) criticism: it’s a care- and thoughtful interpretation, with detailed dynamics, faithfully following the score. Rubinstein uses careful articulation (also in the ornaments) and agogics. Nothing is superficial, every bar has its internal rhythmic tension. The maggiore (Trio) parts are taken a tad faster, just a little outside the agogic “bandwidth” in the minore part. The one other thing I noted: Rubinstein omits the two quaver chords in the right hand, 12 bars from the end—an omission in his score? Hard to believe that this was Rubinstein’s deliberate omission! Overall, an excellent interpretation: as good as it can be on a modern concert grand!

Rating: 4

Rudolf Buchbinder (1975):

1/4 = 45 (approx.), duration: 16’59”

Instrument: modern concert grand

Buchbinder was my first encounter with Haydn’s piano sonatas and variations, on LP. The reacquisition of this interpretation on CD was mostly done for nostalgic reasons. I knew full well that my taste / preferences have moved on over the past 20 years. Indeed, I’m no longer happy with this. It’s good that I also have Rubinstein’s interpretation (see above). This way I know that I’m not (just) blaming the modern instrument, but the artist! It’s a rather boring interpretation, especially in comparison with Rubinstein’s. There’s very limited local agogics & phrasing, mainly large-scale phrases (between the repeat signs). Buchbinder adds a distinct ritardando at the end of every such phrase. Dynamic annotations are often not observed (playing f in lieu of p, i.e., exaggerating crescendi).

Buchbinder plays the repeats — oddly with the exception of the first one in the Trio part of variation I. Within that one part, the triplets following the trills in bars 6 and 7 are not performed properly. Overall, the entire piece is essentially played in the same mood. It’s all a bit harmless and — as stated — boring, and lacking emotional / expressive depth. Finally: in bars 11 and 10 from the end, the two triplets are played essentially the same, even though the second one is meant to be twice as fast.

Rating: 2

Christine Schornsheim (2004):

1/4 = 42 (Andante) / 1/4 = 54 (Trio), duration: 16’34”

Instrument: fortepiano by John Broadwood & Son, London, 1804

The Instrument

Christine Schornsheim is playing a historic fortepiano by Broadwood, from 1804. My first thought now was that given the composition in 1793, an instrument by Walter would have more appropriate. Broadwood was built (and is supposed) to have more power / dynamic bandwidth than the instruments that were available at the time of the composition. In any case, it seemed interesting to compare this instrument to the Walter replica that Andreas Staier is playing (see below). To my amazement, the Broadwood sounds more fragile, often thinner, “glassier”. I don’t think that’s due to microphone placement / recording technique.

The key point one needs to bear in mind that this is not a replica, but a historic instrument. This typically precludes “touching up” the mechanics, etc. (the best one might be able to do is to build a replica based on a careful analysis of the “hardware”). While the strings and the soundboard may be OK, the “coating” (leather or felt) of the hammers (probably the most crucial part ion the sound generation) is certainly not in the original state. Hence, the sound in this recording may be pretty far from what it used to be when the instrument was built. In any case, in its present state, that Broadwood instrument may indeed be close in sound to a Walter fortepiano from the late 18th century!

The Interpretation

Christine Schornsheim starts with a slower tempo than the others. Her articulation and phrasing are detailed, with careful rhythmic elaboration in every bar, with occasional jeu inégal. The Broadwood piano is really singing in the Trio, where she picks up some tempo. The tempo concept in the variations is the same as in the initial presentation of the two themes: slower for the minore parts, faster for the Trio / maggiore section. The Variation II (Andante part, up to the f / ff section leading to the Trio) is played una corda — a nice, ethereal touch. The Trio in that variation is again slightly faster (tre corde), but mostly retains its lovely, gentle character, rather than trying to be virtuosic.

A short, 5-bar cadenza (the same as also played by Andreas Staier) concludes the maggiore section before the mood swings back to the seriousness of the Finale, which goes through some emotional turmoil. An excellent interpretation, overall, internally consistent, rich in expression and emotion!

Rating: 4

Andreas Staier (1993)

1/4 = 48 – 52 (approx.); duration: 15’44”

Instrument: fortepiano by Christopher Clarke, Véron, 1986, after Anton Walter, Vienna, ca. 1792

Here, the Trio is played at the same tempo as the Andante, but Staier uses lots of agogics to support his phrasing. In the exposition and the first variation, the overall tempo is markedly faster than the others: slightly slower in the Trio, compared to Christine Schornsheim. The character of the entire piece is much more dramatic and reminds me of C.P.E. Bach, or composers such as Dussek, or the Mannheim school of composers. This is definitely not the lovely Haydn that some people seem to see in this piece! While the Trio is not differentiated in tempo (there is no tempo annotation), the first variation is taken slightly faster (1/4 = 54 – 60). Variation II is even more dramatic and very virtuosic (especially in the Trio) at 1/4 = 68.

After that second variation, Staier plays a 5-bar cadenza (the same that is also played by Christine Schornsheim, though fairly different in style / emotionality). After a marked, short break, the Finale returns with the original tempo and a more earnest first 24 bars, ending in hesitation and a fermata. But with the following punctuated f chords, Staier suddenly picks up a fast, dramatic pace, then hesitates again for a couple of bars (up to bar 34 of the Finale). Then, the punctuated ff chords start a lengthy, dramatic and virtuosic outburst.

The Influence of the Instrument

After another, more pensive section, 17 bars from the end, there are three sforzati, after which the sustain pedal is to be held for almost 5 bars. Despite claims that the sound of a fortepiano is much shorter than the one of a modern concert grand, this Walter replica has no problem letting the chord from the last sforzato sound, sing for more than 3 bars! 12 bars from the end (still with the sustain pedal held down), Staier shifts the two chords (which Rubinstein omits) down by two octaves, using them to “refresh” the sound from the last sforzato: a very nice effect & idea! For the final p and calando bars, Staier uses the moderator to allow for a whispered ending.

To me, this is clearly the best interpretation among these four. Compared to Christine Schornsheimer’s, it is entirely different in character. But both are valid approaches, I think. Overall, Staier’s interpretation is much more dramatic, more expansive in the dynamics. The piece has drive (without ever sounding pushed) and is much more vivid and expressive than any of the others. Needless to say: the sound of the instrument is excellent. Who would (for this music) ever want to go back to a modern concert grand after hearing this?!

Rating: 5

Piano Music by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809 – 1847)

The CDs

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CD #32

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CD #32: Rubinstein Encores

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp.; LP liner notes on back of CD sleeve

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CDs #136/137

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CDs #136/137: Rubinstein — The Benefit Recital for Israel

Music by Beethoven, Schumann, Debussy, Chopin, Mendelssohn

Arthur Rubinstein

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., track listing on CD sleeve

Rubinstein and Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809 – 1847) has produced quite a number of compositions for the piano. Today, unfortunately, his oeuvre for piano solo shows very limited presence in concert halls and in the music market in general. Among the compositions which are still played in concert halls, the “Lieder ohne Worte” (songs without words) are the most popular ones. That’s a genre that Mendelssohn created for himself. Very few other composers later picked up this concept / idea.

I don’t know how much solo music by Mendelssohn Arthur Rubinstein really played in his life. But among the almost 110 hours of music in the “Complete Album Collection”, only one single, 2-minute piece has survived: No.4 from volume 6 of Mendelssohn’s “Lieder ohne Worte”, op.67: the “Spinnerlied” (Spinner’s Song), played as an encore. Apart from that, the only Mendelssohn in Rubinstein’s repertoire is a recording of the piano trio No.1 in D minor, op.49.

The collection includes two instances of the “Spinning Song”:

- as a part of a collection of encores, recorded in 1950 (CD #32), and

- as an actual encore in his Recital for Israel, given on January 15, 1975 in Pasadena (CDs #136/#137). After that encore, Rubinstein only made one more live recording, in 1976 (Brahms piano concerto No.1, with Zubin Mehta and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra).

The “Spinning Song”

The 1950 recording is of course not an encore, but a studio recording of a piece that often served as encore. Rubinstein wanted to present the pieces he uses as encores in an official recording. This is inevitably done under the regime of Rubinstein’s “recording standards”: he focused on being faithful to the piece and the composer, making sure the result is a recording that he can stand behind (for a while!). I do not imply that he wouldn’t aim to be faithful in his concerts, but a live interpretation always adds an element of spontaneity that is lacking from studio recordings. This can be exemplified in the two recordings above.

In addition, there is of course the element of time. At the time of the the studio recording, Rubinstein was 63, while in the Benefit Recital for Israel he was 88 and close to the end of his active career:

- The studio recording (1’44”) is virtuosic, clear / transparent, with constant drive forward, despite some agogics / slight rubato: a very good interpretation!

- The concert recording is slightly slower overall (1’55” without the announcement and the applause). It starts at nearly the same tempo, but Rubinstein occasionally slows down or holds the flow in order to maintain precision and clarity. Still, one can hear the effect of age and (maybe even more so) of a long concert of more than 1.5 hours. The coordination, the clarity and precision in the earlier recording are definitely better. Also, here, the sustain pedal occasionally remains held down for too long. But despite these shortcomings it remains an interpretation that is worth hearing, apart from the fact that it is the last recording of a solo piece played by Rubinstein!

Listening Diary Posts, Overview