Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Sonatas Nos.8 & 14

Media Review / Listening Diary 2012-12-31

2012-12-31 — Original posting (on Blogger)

2013-08-07 — New standard layout applied

2014-11-08 — Re-posting as is (WordPress)

2015-08-20 — Added references to Brautigam’s complete sonata recording

2016-07-10 — Brushed up for better readability

Table of Contents

- Beethoven, Piano Sonata No.8 in C minor, op.13, “Pathétique”

- Beethoven, Piano Sonata No.14 in C♯ minor, op.27/2

- The CDs

- Comments by András Schiff

- Comments on the Recordings

- Paul Badura-Skoda (1969,Bösendorfer 290 Imperial)

- Daniel Barenboim (1984)

- Wilhelm Backhaus (1958)

- Friedrich Gulda (1967)

- Artur Schnabel (1935)

- Mikhail Pletnev (1988)

- Emil Gilels (1980)

- Jos van Immerseel (1983, fortepiano by Conrad Graf, 1824)

- Ronald Brautigam (2003, fortepiano by Paul McNulty, 2001, after Walter & Sohn, 1802)

- Timing Comparison Table

- András Schiff, Lectures on the Beethoven Piano Sonatas

- Addendum

Beethoven, Piano Sonata No.8 in C minor, op.13, “Pathétique”

I just added one new recording of this piano sonata to my collection, with Jos van Immerseel — but as I had already listened through all Beethoven piano sonatas (in 2010, before I started blogging), I only did a comparison with a small collection. Here are the recordings in my short comparison (I did not re-evaluate all recordings, see below):

The CDs

Friedrich Gulda

Beethoven: The 32 Piano Sonatas, The 5 Piano Concerts

Friedrich Gulda (Horst Stein, Vienna Philharmonic)

Universal 476 8761 (12 CD, stereo); ℗ / © 2005

Emil Gilels

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas

DG 00289 477 6360 (9 CD, stereo); ℗ 1972 / © 1996

Jos van Immerseel

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas opp.13, 27/2, 6 Bagatelles op.126, Andante favori WoO 57

Jos van Immerseel (Fortepiano by Conrad Graf, 1824)

Accent ACC 78332 (CD, stereo)

Ronald Brautigam

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas opp.13, 14/1, 14/2, 22

Ronald Brautigam (Fortepiano by Paul McNulty, 2001, after Walter & Sohn, 1802)

BIS-SACD-1362 (SACD/CD); ℗ / © 2004

Beethoven: The Complete Piano Sonatas

Ronald Brautigam (Fortepiani by Paul McNulty)

BIS-SACD-2000 (9 SACD/CD); ℗ 2004 – 2010 / © 2014

Booklet: en/de/fr

Ratings

And here are my findings (the five recordings with ratings below 3.0 were not re-evaluated):

- Wilhelm Backhaus (1958): rating 1.3 (1 / 2 / 1)

- Daniel Barenboim (1984): rating 2.0 (2 / 2 / 2)

- Paul Badura-Skoda (1969, Bösendorfer 290 Imperial): rating 2.0 (2 / 2 / 2)

- Artur Schnabel (1935): rating 2.3 (2 / 3 / 2)

- Edwin Fischer (1952): rating 2.7 (3 / 3 / 2)

- Friedrich Gulda (1967): rating 3.0 (3 / 3 / 3)

- Jos van Immerseel(1983): rating 3.0 (3 / 3 / 3)

- Emil Gilels (1980): rating 4.0 (4 / 4 / 4)

- Ronald Brautigam (2003): rating 5.0 (5 / 5 / 5)

Note that in the above ratings I merely tried exploiting the range 1 – 5 given by iTunes. Backhaus’ interpretation is not “bad” — it just felt like the weakest recording in this selection.

Comments on the Recordings

Jos van Immerseel

I must say, I was somewhat disappointed by Jos van Immerseel‘s interpretation. Not that it is bad at all — but I had higher expectations. I expected it to be at the same level as Ronald Brautigam‘s recording. Here’s where Jos van Immerseel‘s interpretation fell slightly short:

- In the fast movements, the artist shows a tendency to underplay (rush over) small note values / ornaments.

- In the Adagio cantabile, he carefully keeps both hands synchronous at all times. This causes the accompaniment to follow any agogics in the melody, and this again causes substantial disruptions in the musical flow. Yet, he still appears to lack time for some of the ornaments / figures in the slow movement.

- From the liner notes I take that this is a historic fortepiano by Conrad Graf, Vienna, from 1824, which definitely makes this an interesting recording. However, for the early piano sonatas, the lighter fortepianos by Walter would have been a better choice, see below. The Graf fortepiano sounds rather somber, even without the moderator, and it can’t match the singing tone of the Walter models. On the other hand, van Immerseel does use the moderator (a piece of felt that could be pulled between the hammers and the strings). This adds some nice colors to sections of the slow movement.

- One should keep in mind, though, that this dates back 20 years before Ronald Brautigam’s recording. It therefore is closer to early “HIP” performances such as by Jörg Demus or Paul Badura-Skoda (prominent fortepiano players in the 70’s) than to current “HIP” performances by artists such as Ronald Brautigam or Kristian Bezuidenhout. The latter certainly have taken up many newer findings from the “HIP scene” about musical interpretation, articulation and expression at Beethoven’s time.

Ronald Brautigam

On the other hand, Ronald Brautigam convinced me more than in 2010, when I listened to these interpretations last time: I originally had given him a rating of 4.0 (without direct “competition” I hesitated giving a 5.0 rating initially) — now I could not resist giving him an “upgrade”:

- For me, his fast movements (in this sonata) are vastly more dramatic, more compelling, and feature much better articulation. Every detail is there, there’s no rushed ornament, not a single superficial passage.

- The slow movement maintains the musical flow, even though he uses just as much agogics as van Immerseel (if not even more); but he does not try to stay strictly synchronous with both hands: where appropriate, he gives the melody some additional “play”, sometimes use moderate “arpeggiando” (slight asynchrony) — which also enhances the transparency.

- He is in the fortunate position to play an excellent replica of a Walter fortepiano from 1802, which is hard to beat in its singing tone, the clarity, the agility in articulation. And it is the better choice here because it simply is what fortepiani were like at the time of this composition.

Among the “classic” / traditional interpretations, Emil Gilels for me is clearly the most convincing one in the above selection, outperforming the restrictions / limitations (!) of playing early Beethoven on a modern concert grand.

Beethoven, Piano Sonata No.14 in C♯ minor, op.27/2

The newly acquired CD also included an interpretation of the Beethoven piano sonata in C♯ minor, op.27/2, the so-called “Moonlight Sonata”. I knew that the “Moonlight” attribute was not Beethoven’s — but it wasn’t till after listening to the lecture series on the Beethoven piano sonatas that András Schiff has given in recent years at Wigmore Hall (all of which can be downloaded) that I now listened with the score. And I must say: Schiff’s explanations were extremely helpful in listening to this music with “fresh / new / unbiased ears” — I can only recommend listening to these presentations!

The review below is somewhat cursory, but did include all recordings. The CD collections with the recordings by Friedrich Gulda,Emil Gilels, and Jos van Immerseel were presented above — here are the other recordings in this brief comparison:

The CDs

Paul Badura-Skoda

Beethoven: The 32 Piano Sonatas

Paul Badura-Skoda (Bösendorfer 290 Imperial)

Gramola 987 42/50 (9 CDs, stereo)

Daniel Barenboim

Beethoven: The Piano Sonatas Nos.1 – 15

DG 413 759-2 (6 CDs, stereo); ℗ 1984

Wilhelm Backhaus

Beethoven: The 32 Piano Sonatas

Decca 473 7198 (8 CDs, mono / stereo); ℗ 1953 – 1969 / © 2006

Artur Schnabel

Beethoven: The 32 Piano Sonatas

Artur Schnabel (recorded in London, 1932 – 1935)

Regis / Forum FRC 6801 (8 CDs, mono)

Mikhail Pletnev

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas opp.27/2, 53, 57

Virgin Classics 0946 363280 2 7 (CD, stereo); ℗ 1989 / © 2006

Ronald Brautigam

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas opp.26, 27, 28

Ronald Brautigam (Fortepiano by Paul McNulty, 2001, after Walter & Sohn, 1802)

BIS-SACD-1473 (SACD/CD); ℗ / © 2006

Beethoven: The Complete Piano Sonatas

Ronald Brautigam (Fortepiani by Paul McNulty)

BIS-SACD-2000 (9 SACD/CD); ℗ 2004 – 2010 / © 2014

Booklet: en/de/fr

Comments by András Schiff

András Schiff’s comments turned out to be instrumental for judging these recordings! Overall, I could not agree more with his findings. Schiff obviously went back to the originals (Beethoven’s manuscript is available for this sonata) and did thorough research, so they are clearly more than just a matter of opinion of taste. The points to take home in particular from Schiff’s comments:

- The first movement (Adagio sostenuto) is written as alla breve, not as 4/4. This implies a faster tempo than commonly expected, as there are only two beats per bar. Within this comparison, all artists but Artur Schnabel fell short on this point.

- The first movement is not only has an annotation Adagio sostenuto and “sempre pp e senza sordini”, but in addition carries the statement “Si deve suonare tutti questo pezzo delicatissimamente e senza sordini“, i.e., all of this piece must be played with utmost delicacy and without dampers. This implies a “blurring effect” due to the mixing of the harmonies — especially when really played alla breve. In my opinion, none of the recordings really fulfills this requirement — mainly because most of them play this far too slow for this effect to work — and most even clearly disregard the spelled out pedaling instruction.

- The last movement again has explicit, accurate and critical pedaling instructions (the closing staccato beats at the end of each phrase in the main theme must be performed with pedal). Most pianists do indeed observe these, though.

Comments on the Recordings

Finally, my comments on the interpretations listed above:

Paul Badura-Skoda (1969,Bösendorfer 290 Imperial)

- [1]: 6’03” — played as 4/4: too slow; worse than that: this sounds like a commercial for the Bösendorfer 290 Imperial: Badura-Skoda transposes the left hand down by an octave (into the extra keys on that piano), which clearly violates the composer’s intent (Beethoven could not even have dreamed of such a tonal range). Yes, the depth sounds impressive — but it’s not even nice in this piece. Maybe the idea was to enhance the blurring effect (see above) — however, for one, at this tempo the blurring is hardly noticeable anyway, plus, I actually doubt that the pedal is kept down throughout the movement, as indicated in the score.

- [2]: 2’23” — there’s this very slight arpeggiando / soft articulation that to me looks merely sloppy, and in the Trio the left hand is again transposed down: no, thanks!

- [3]: 6’45” — some rushed parts, articulation often superficial, rhythmically inaccurate at times, and often the bass notes sound over-enhanced (sound management to demonstrate the piano’s depth, or transposing again??). It’s at least questionable whether the last chords should be played with the pedal down — the score has no indications to that effect.

- Rating 1.3 (1 / 1 / 2)

- Recommendation: no!

Daniel Barenboim (1984)

- [1]: 6’35” — played as 4/4, and much too slow, pedal not kept down

- [2]: 2’12” — slightly superficial?

- [3]: 7’50” — again, some slight superficialities.

- Rating 2.0 (2 / 2 / 2)

- Recommendation: no

Wilhelm Backhaus (1958)

- [1]: 5’43” — played as 4/4: too slow, but at least singing in the melody. Is this a Bösendorfer 290 Imperial — and is he transposing the left hand down as well?? I suspect at least the former, given the dominating bass sonority.

- [2]: 2’19” — some odd accelerations, and some arpeggiandi that I dislike

- [3]: 7’29” — dynamic not always accurate, some rushed passages

- Rating 2.3 (3 / 2 / 2)

- Recommendation: not my favorite, clearly.

Friedrich Gulda (1967)

- [1]: 6’30” — played as 4/4, and much too slow, pedal not kept down. At least there’s singing in the melody, and one can feel the big phrases despite the slow tempo.

- [2]: 2’31” — more neutral than Gilels, with accurate, careful articulation

- [3]: 6’54” — in favor of the presto agitato, Gulda hammers away, ignoring the severe distortions (beyond any aesthetics!), but — as expected with this artist — it’s rhythmically well controlled and accurate. The pedaling on the staccati is done as prescribed, though I suspect some extra pedaling in other parts of the movement.

- Rating 3.0 (3 / 3 / 3)

- Recommendation: not the worst of the traditional interpretations,but — in my opinion — quite far away from Beethoven’s intent

Artur Schnabel (1935)

- [1]: 4’55” — this interpretation— albeit rather slow — is the only one where one can sense the alla breve notation. The melody is singing. There is noticeable blurring in various parts of the movement. Although Schnabel is known as having been among the most meticulous ones in reading a score, I doubt that the pedal is really kept down at all times. There was of course the unwritten “rule” that one ought to use the dampers whenever mixing of “incompatible harmonies” might occur!

- [2]: 2’13” — a good Allegretto.

- [3]: 6’30” — a fast, dramatic, even explosive interpretation with a clear concept — the fastest one in this comparison, even so with dramatic stringendi! At this tempo, the pedaling around the closing staccati at the end of the phrases in the main theme are hardly audible. The Coda (including the extensive cadenzas) has no pedaling instructions. Schnabel is keeping the pedal down for the two long scales at the end of the cadenza, and the broken falling scale is fast, without ritardando. Given that cadenzas in classic times were generally meant to be “con alcune licenze“, this artistic freedom is legitimate, I think.

- Rating 3.3 (3 / 3 / 4)

- Recommendation: an impressive interpretation, of more than just historic value!

Mikhail Pletnev (1988)

- [1]: 7’16” — much, much too slow, even so it’s played as 4/4! It’s singing — sort of, as the melodies in the outer voices run “out of sight”, i.e., are hard to keep track of. The pedaling instructions are ignored, of course. For me, this is a complete misconception of this movement (more than just eccentric).

- [2]: 2’15” — excellent phrasing and articulation, expressive

- [3]: 8’05” —Pletnev clearly ignores the pedaling instructions around the staccati, and the articulation sometimes appears sloppy (though it’s likely a deliberate decision of the pianist to use soft articulation, or to play some chords as arpeggio).

- Rating 3.3 (2 / 5 / 3)

- Recommendation: no, I can’t really recommend this — too eccentric / off the track, overall.

Emil Gilels (1980)

- [1]: 6’06” — played as 4/4: too slow, and the pedaling instructions are not observed. That’s too bad, as otherwise it is a very expressive, singing interpretation with good phrasing and excellent articulation!

- [2]: 2’32” — excellent phrasing and articulation (minor exception: the use of sustain pedal covers a few staccati and rests), very expressive!

- [3]: 7’16” — very dramatic and expressive — a bit too forceful (“too much modern concert grand”) in my opinion, especially when considering the dynamic limitations of the fortepiano at the time of creation of this composition.

- Rating 3.7 (3 / 4 / 4)

- Recommendation: Impressive, especially in the second and third movement!

Jos van Immerseel (1983, fortepiano by Conrad Graf, 1824)

- [1]: 5’39” — played as 4/4: too slow. Jos van Immerseel may be keeping the pedal down (I don’t think he does from beginning to end) — but as he is using the moderator at the same time (throughout this movement — why?), the harmonics are very much dampened, almost suppressed. The blurring effect is virtually absent — both by this and due to the slow tempo.

- [2]: 2’26” — nicely singing (the advantage of the fortepiano!); the articulation is a bit on the soft side (arpeggiandi), which to me defeats the Allegretto character of the movement.

- [3]: 7’17” — unfortunately, van Immerseel does not observe the pedaling notation (if not even completely reversed!). There are some rushed / superficial passages, almost giving the impression of incomplete tempo control.

- Rating 3.7 (4 / 4 / 3)

- Recommendation: Among the fortepiani, the Walter models are the better choice for this period in Beethoven’s oeuvre (see below). I have the slight suspicion that van Immerseel mainly wanted to demonstrate the scope of possibilities of the historic Graf fortepiano, and hence may not always have used the settings / playing manners that would have been adequate / appropriate for this sonata. Among the historically informed interpretations, I prefer Brautigam’s recording below.

Ronald Brautigam (2003, fortepiano by Paul McNulty, 2001, after Walter & Sohn, 1802)

- [1]: 5’49” — played as 4/4: too slow! The pedaling is better than with most others (though I don’t think he keeps it down at all times). However, due to the slow tempo, the blurring effect is limited to the duration of a bar, at most. Too bad, as otherwise Brautigam’s playing is very expressive, differentiated, careful. To me, it’s clearly the best interpretation, apart from the 4/4 & the tempo flaws!

- [2]: 2’05” — I’d prefer the Allegretto part without the arpeggiando playing — but the singing tone of the Walter fortepiano is marvelous!

- [3]: 6’52” — excellent: this really is Presto agitato! Dramatic, with accurate dynamics, pedaling / articulation and transparency, and without losing control. What more does one need to demonstrate the superiority of a fortepiano over the modern concert grand?

- Rating 4.3 (4 / 4 / 5)

- Recommendation: My clear favorite, overall! If you dislike historically informed performances, I can recommend Gilels instead.

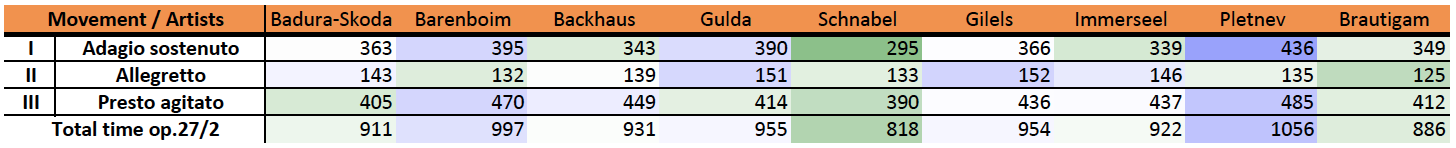

Timing Comparison Table

Finally, a table with the times (in seconds) for the individual movements and the total time for the sonata, with color coding, where green indicates fast(er) playing (shorter time), and blue indicates slow(er) playing:

András Schiff, Lectures on the Beethoven Piano Sonatas

I have mentioned this above: the Hungarian pianist András Schiff has given a series of presentations / introductions to all of Beethoven’s piano sonatas; in each of these events he was presenting 3 or 4 piano sonatas that he was going to play the following day(s), and he was doing this for the entire cycle. I know of art least two such lecture series (none of which unfortunately I was able to attend): one series (presumably in German) he was giving in Zurich. For the early sonatas he was using a Bösendorfer grand (presumably not the 290 Imperial!), for the late(r) sonatas he was using a Steinway grand. The same cycle he was also giving (in English, of course) at Wigmore Hall in London in 2004 – 2006.

Fortunately, his entire Wigmore hall series is now available for download, nicely split into one track (20 – 40 minutes typically) per sonata. I put all of this onto my iPod and listened to the entire cycle in planes, airports, and at the hotel earlier this month, when I was asked to spend a week in California — and I can only recommend this series: it’s extremely instructive, insightful — and at the same time witty, entertaining, and full of excerpts & examples played on the piano (including pieces from other composers, from Bach to Brahms). As mentioned before: Schiff has done his research, his statements are well-founded cod conclusive — and even if you don’t agree with 100% of what he states, this will change your perception of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, guaranteed!

Addendum

For the non-pianists: I use pocket scores (typically Lea Pocket Scores or Kalmus) to follow this music:

- Sonata No.8 op.13, “Pathétique”: —Find pocket score on amazon.com (#ad) —

- Sonata No.14 op.27/2, “Moonlight”: —Find pocket score on amazon.com (#ad) —

Listening Diary Posts, Overview