Piano Recital: Grigory Sokolov

Beethoven / Schubert

KKL Lucerne, 2018-11-22

2018-12-01 — Original posting

Auf der abgedunkelten Bühne mit dem Fokus ganz auf der Musik — Zusammenfassung

Das Programm eröffnete mit Beethovens Klaviersonate in C-dur, op.2/3 und dem 11 Bagatellen, op.119. Aber war das wirklich Beethoven? Entsprach die Interpretation Beethovens Vorstellung? Grigory Sokolov präsentierte die beiden Werke ganz nach seiner Manier: über-sorgfältig in Anschlag und Dynamik, über-akzentuiert in der Artikulation, speziell im Staccato. Das Zeitmass bewegte sich praktisch ständig im moderaten Bereich. Sein Spiel war perfekt kontrolliert, über-kontrolliert. Der Musik fehlte die Aussagekraft. Wo war das Feuer im Allegro con brio? Wo der Scherzo-Charakter im dritten Satz?

Die 11 Bagatellen kamen etwas lebendiger, eher den Vorgaben Beethovens entsprechend daher, vor allem die Nr.6-10. Jedoch Beethovens humoristische, kleine Einschübe blieben meistens “auf der Strecke”.

Ich kann nicht verleugnen, dass ich mich während Schuberts posthumen 4 Impromptus, op.142 (D.935) gelegentlich langweilte. Mir fehlten die Aspekte der Verzweiflung, der Verlorenheit in Schuberts Spätwerk beinahe völlig.

Erst mit Schuberts Impromptu Nr.4 in As-dur, als erste von insgesamt sechs Zugaben, gelang dem Pianisten der Höhepunkt des Abends: eine absolut beeindruckende Wiedergabe! Singende Kantilenen, dramatische Momente, lange Phrasierungsbögen, sowie natürlich sorgfältigste Dynamik und Artikulation in exzellenter Balance—warum nicht mehr von dieser Art?

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Concert & Review

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.3 in C major, op.2/3

- Beethoven: 11 Bagatellen , op.119

- The Performance

- No.1 in G minor: Allegretto

- No.2 in C major: Andante con moto

- No.3 in D major: A l’Allemande

- No.4 in A major: Andante cantabile

- No.5 in C minor: Risoluto

- No.6 in G major: Andante — Allegretto

- No.7 in C major: Allegro, ma non troppo

- No.8 in C major: Moderato cantabile

- No.9 in A minor: Vivace moderato

- No.10 in A major: Allegramente

- No.11 in B♭ major: Andante, ma non troppo

- The Performance

- Schubert: Four Impromptus, op.posth.142, D.935

- First Conclusions

- Encores

- Final Conclusion

Introduction

This year’s Lucerne Piano Festival offered a chance for me to experience a live performance of the Russian pianist Grigory Sokolov (*1950, see also Wikipedia) in Lucerne’s KKL (Culture and Convention Center Lucerne).

The Artist

Sokolov has a big fan community—there is actually pretty much of a cult around him. He cultivates this (purposefully or not?) by not doing studio recordings, by giving a very limited number of concerts (solo recitals only) at selected venues.

Sokolov is carefully composing and preparing his programs, and he tours the stages with one program only for six months, before switching to the next set of works. And he is meticulous in his preparations, about the stage setup, the instrument (which must not be older than five years), the lighting…

Grigory Sokolov has of course long been a familiar name to me. In fact, he is so well-known that I don’t need to spend more words on introducing the artist. I have, however, discussed selected of his few recordings in earlier blog posts.

Expectedly, the concert was sold out. When my wife and I were looking for affordable seats, we were just able to book into the left edge of the top row in the fourth balcony: the most distant seats, just under the ceiling. This might sound odd. However, I knew beforehand that from the point-of-view of acoustics, these seats (row 9, seats 27 & 28) were as good as any other balcony seats—on any balcony, actually.

Program

For his current recital program, Grigory Sokolov selected works by Beethoven and Schubert. However, it is not unusual for this artist to extend the program by a series of encores:

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827): Piano Sonata in C major, op.2/3

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827): 11 Bagatellen, op.119

(Intermission) - Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828): Four Impromptus, op.posth.142, D.935

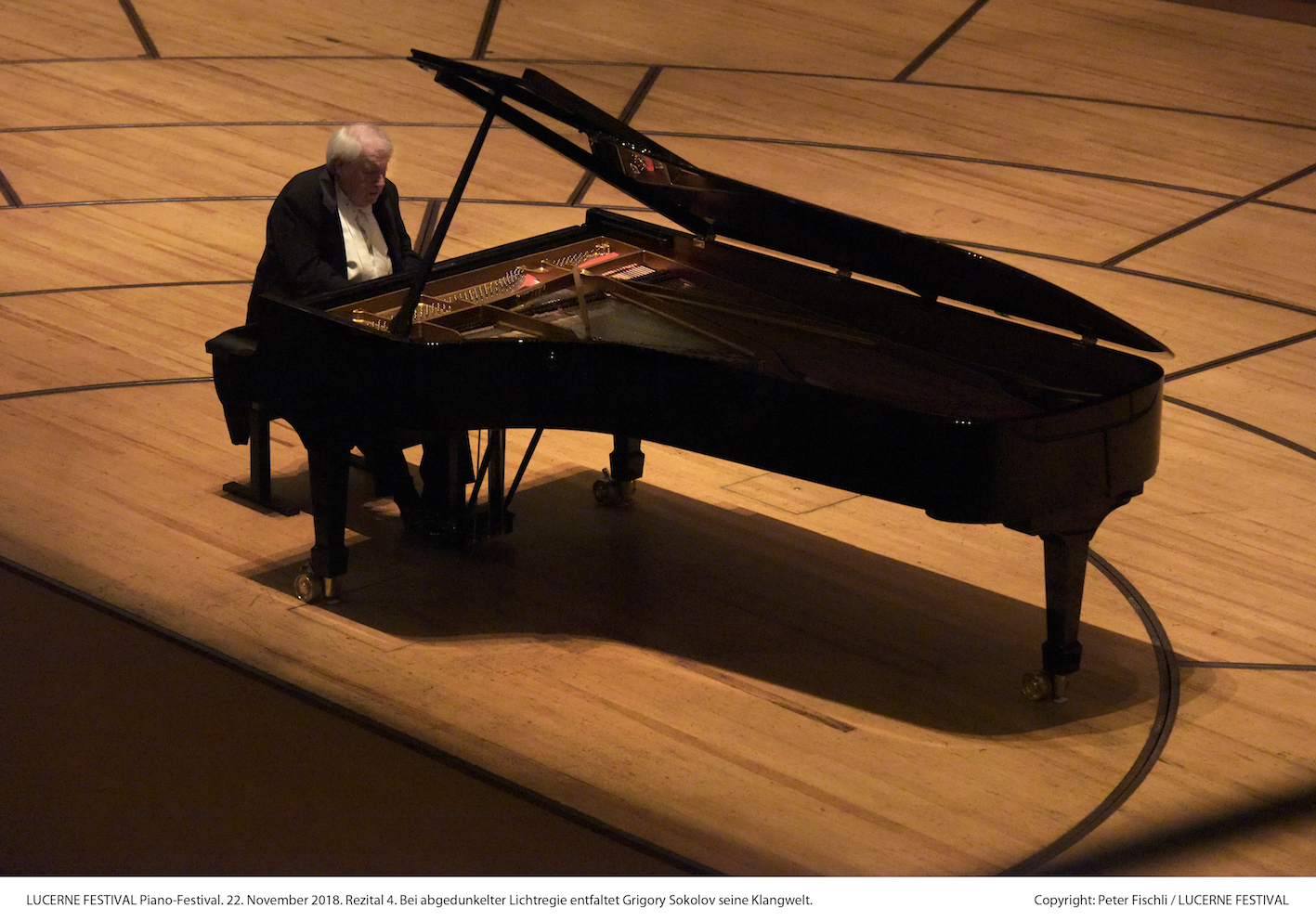

As in all classical concerts, the lights in the auditorium were dimmed for the recital. However, Sokolov wanted the light on the stage to be even darker. As one critic put it: the focus should be entirely on the music.

Concert & Review

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.3 in C major, op.2/3

1796, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) published his first three piano sonatas as his second “official work”. The third of these compositions is the Piano Sonata No.3 in C major, op.2/3, featuring the following movements:

The Performance

Sokolov’s appearance on stage, the way he is playing and moving while playing are all very well-documented on public (amateur) videos. Even though I was sitting in the most distant corner of the venue, I could easily watch his hands on the keyboard. This only confirmed what I knew perfectly well from postings on social media, etc., so I will not comment on that aspect here.

I. Allegro con brio

No doubt: Sokolov’s “handwriting” was very obvious right from the first bar: careful touch & dynamics, almost over-careful, occasionally over-accentuated articulation, especially with the staccato (which one might call Sokolov’s specialty!). His tempo was natural, or rather moderated, the playing altogether unexcited—nothing special, one is tempted to state.

However, Sokolov being who he is, could not resist leaving his footprint in the sonata: in bars 28 and 34 he changed Beethoven’s acciaccaturas into appoggiaturas (starting the bars with two semiquavers), for no obvious reason. That change may sound minute, insignificant—however, everybody who knows the sonata will have noticed this instantly.

Control, Perfection

Sokolov repeated the exposition. His playing (touch, articulation, dynamics, agogics, the balance between the hands) remained perfectly controlled, diligent, also the slight change to a faster tempo for the second theme in bar 39, or the f / sf outbreaks in the last part of the exposition. One might call this Apollonian perfection. But is this what the composer had in mind?

This was the last of three sonatas in first “official” set in this genre, and I’m sure Beethoven wanted to make a big “splash”—and here, it all was so perfectly controlled that the music lacked all excitement. To say the truth: I started to feel bored before the second pass of the exposition was over.

The music felt so devoid of all revolutionary, rebelling aspects. The Steinway D-274 concert with its perfect sound balance across the keyboard further smoothed out any remainder of colors that fortepianos at Beethoven’s time would have exposed. The performance may indeed have been near-perfect—to me, it was primarily very uniform, and—worse than that—predictable, lacking all surprises.

The tempo change for the second theme was identical in both passes of the exposition, as well as in the recap section, and in sf and ff, the pianist carefully avoided driving the piano into distortions. Beethoven? The young Beethoven? Even Mozart and Haydn were more provocative than this in their sonatas. And: where was the con brio???

★★★½

II. Adagio

Perfection also here, be it in the perfect articulation already in the first bars, or in the immaculate touch and dynamic control, when in bar 9, Sokolov took back the volume to the finest ppp. The E minor section started with perfectly measured demisemiquavers, and whenever the left hand reached up for its melody fragments in the descant, the artist momentarily took back the tempo for more expression in the left hand.

The intent was clear—however, the artist did not catch up fully after these motifs, and so, over that section, the pace gradually slowed down, the tension dropped. Also the ff outbreaks remained very (perfectly) controlled, as also the slight lag in the left-hand motifs. Ethereal or presumptuous??

★★★

III. Scherzo: Allegro — Trio

Again, the tempo remained restrained, very, very controlled, measured, if not comfortable, even a bit sterile, lacking all excitement. Where is the Scherzo character? True, “numerically”, it was an Allegro on the crotchets—however, the way Beethoven wrote the movement, one feels the bars, not the crotchets. That was perhaps a Scherzo of an old man (the composer, not the artist), not the slash that was meant to open the doors to concert halls. For sure, one could not blame Sokolov for extroverted virtuosity in this!

★★★

IV. Allegro assai

No surprises: perfect staccato chord chains, the tempo diligently selected, such that the semiquavers never sounded rushed. The one true highlight here was in the highly differentiated dynamics in the transition bars 53 – 64. The decision to take back the tempo at the dolce in bar 103ff didn’t quite convince me, though. And the middle section also had the tendency to lose some tension.

★★★½

Let there be no doubt: I’m merely describing how the music “worked on me”. Perfection as such (and as present in Sokolov’s playing) is not a musical quality—at best, it is a foundation for a good performance. And when I mentioned the word “presumptuous” above, that’s the music, not the artist. I know from many sources that Grigory Sokolov is a very nice and overwhelmingly friendly character who often attends recitals by colleagues and visits them in the artist’s room after the concert. So: sorry…

Overall Rating: ★★★

Beethoven: 11 Bagatellen, op.119

Beethoven wrote first sketches for five of these Bagatellen already before 1800, and up to 1803. In 1820, he created five more Bagatellen, which he published separately in 1821. In 1822, No.6 was added to the initial set of five pieces. 1823, the English publisher then printed these six together with the five published in 1821, all under the title “11 Bagatellen, op.119“:

- G minor: Allegretto

- C major: Andante con moto

- D major: A l’Allemande

- A major: Andante cantabile

- C minor: Risoluto

- G major: Andante — Allegretto

- C major: Allegro, ma non troppo

- C major: Moderato cantabile

- A minor: Vivace moderato

- A major: Allegramente

- B♭ major: Andante, ma non troppo

The Performance

Sokolov did not leave the podium, but just waited for the applause to end, and continued with these Bagatellen. One may argue that the sketches for the first five of these pieces date from the time when Beethoven published his op.2/3. Consequently, the artist presented the Bagatellen very much in line with the preceding sonata. It’s in the nature of a Bagatelle (a “little nothing”) that the music is less pretentious than a sonata movement. If an artist wants to see them as ethereal, so be it.

No.1 in G minor: Allegretto

Actually, in Sokolov’s interpretation, the climax of Bagatelle No.1 offered more excitement than much of the sonata. Interestingly, the artist made the single ornament in that short piece, the turn in bar 10, stand out—a short moment of humor, or just trying to catch the listener’s attention?

No.2 in C major: Andante con moto

A carefully articulated miniature, especially in the left hand. Not sure why Sokolov deviated from the standard score—a short memory lapse? It wasn’t too obvious to the listener, though…

No.3 in D major: A l’Allemande

The first 16 bars were very soft and delicate, refined. And even though that segment was all pp and below, the semiquaver signals in the descant were shining like sprinkles of starlight. The second part was f, setting stronger accents—without building up too much drama, of course. The da capo appeared with repeats, which again balanced nicely against the coda. The highlight of the evening so far.

No.4 in A major: Andante cantabile

… and the highlight continued: beautiful, unpretentious, calm, reflective—a true Bagatelle!

No.5 in C minor: Risoluto

In Sokolov’s hands, the Risoluto was rather moderated: I could easily see this as forming a stronger, more colorful (and maybe more aggressive) accent in the series.

No.6 in G major: Andante — Allegretto

Clearly, the style of No.6 is different, the piece more complex, more varied in its character: Beethoven’s last addition to the series, over 20 years after the first sketches. One could see this as really humorous, if not joking piece; Grigory Sokolov stayed with the leggiermente annotation in the Allegretto part. I did miss some of the humor, though.

No.7 in C major: Allegro, ma non troppo

I think this should be even more humorous than No.6—it wasn’t. The second part with the long trill in the bass and the strong acceleration in the right hand evoked strong memories of the climax in Prélude No.8, La chanson de la folle au bord de la mer, from the 25 Préludes dans tous les tons majeurs et mineurs pour le piano ou orgue, op.31 by Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813 – 1888). Could this be real??? Did Alkan perhaps quote Beethoven’s Bagatelle??? The linkage sounds rather odd, though…

No.8 in C major: Moderato cantabile

Here, there was a strong contrast between the serene first part (with the nicely highlighted punctuations) and the more serious, darker, reflective second half.

No.9 in A minor: Vivace moderato

Sokolov took this as a moody piece by the late(r) Beethoven—which it really is: carefully played, detailed and diligent in articulation and dynamics—excellent! Sure, more aggressive, rebellious views are possible here—but this version is certainly very valid.

No.10 in A major: Allegramente

The shortest piece for piano ever? a lovely miniature!

No.11 in B♭ major: Andante, ma non troppo

With this Bagatelle, Grigory Sokolov clearly formed the musical and emotional climax of the series. And he gave that piece the most detailed and careful articulation and dynamics. Again very good!

After the disappointment with the Sonata op.2/3, the Bagatellen—especially Nos.6 – 10—offered some compensation.

Rating: ★★★★

Schubert: Four Impromptus, op.posth.142, D.935

In 1827, Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) composed two sets of four Impromptus. He published the first one under the title “4 Impromptus, op.90” (later to become D.899). The remaining four of the Impromptus were published only after the composer’s death, in 1839, under the title Four Impromptus, op.posth.142 (later known as D.935):

- No.1 in F minor: Allegro moderato

- No.2 in A♭ major: Allegretto — Trio

- No.3 in B♭ major: Andante (Theme with 5 Variations)

- No.4 in F minor: Allegro scherzando

The Wikipedia article mentions speculations (by Schubert’s contemporaries) about these Impromptus being a “hidden sonata”, just split up because this would yield more income. The cyclic sequence of keys seems to lead towards such a conclusion—but there are also arguments that speak against this.

The Performance

Impromptu No.1 in F minor: Allegro moderato

The annotation includes moderato—and (sadly) that attribute applied to the entire piece: none of Schubert’s despair (and he definitely was desperate, knowing that his life was going top end very soon!), everything was moderate: sections with lightening, as much as downturns, the melancholy, the drama, and the dynamics. In a way, a very nice Lied, certainly well and carefully performed, with decent agogics—but barely more than that.

Yes, there were very nice details, such as the transition in bar 50, the beautiful singing in the cantilenas, the touching details in the dynamics. However, where were the tears that the composer must have spent when writing this? Where the violent eruption in bars 115 – 123?? Some may claim that Schubert was expressing despair through beauty—the score tells me otherwise! Finally: Sokolov persistently played the fz chords in this Impromptu softer than the surrounding notes—why???

★★★½

Impromptu No.2 in A♭ major: Allegretto — Trio

The theme is all pp. With the exception of the slight highlight in bars 13/14, Sokolov kept the dynamics very soft. He did differentiate though, through several, distinct ritenuti, which gave these 16 bars a very hesitant, retained character. The ff after the double bar was—just very nicely played, but lacked pretty much all drama. The first pass of the second part ended with hesitation, a distinct question mark in bars 43 – 46—strangely, the second pass lacked that differentiation.

The Trio was mostly placid, peaceful, unhurried in the tempo. The artist lifted out the melody in the first notes of the triplet chain in the descant, The climax in the short C major section (bars 67 – 76), culminating in the long bass trill, was very intense and beautifully formed. The final part, starting around bar 96 was almost devoid of despair and resignation—beautifully played, though…

★★★

Impromptu No.3 in B♭ major: Andante (Theme with 5 Variations)

The theme: technically perfect (articulation and dynamics)—but very (far too?) restrained, if not even lacking life. For once, I think that the theme is not the place to express resignation. To me, this comes later, in the variations, and soon enough! Here, variation No.1 continues very much along the same lines: just a nice Lied—I’m sorry…

Variation No.2: not much different initially. The second part looks more dramatic in the score—but here, it was merely a nice dynamic arch—as if it was a verse from the Lied “Die Forelle” op.32. D.550. The following Variation No.3 was rather heavy, slow—slightly dramatic only just in the second part (bars 72 – 77).

Variation No.4: did I read this correctly as joy and serenity, if not carefree—as if it was a piece from a few years earlier? Variation No.5 was more of a disappointment: with the exception of the four dramatic bars (110 – 113) in the center, this felt like an example of an artist ruining a piece by excess diligence and carefulness—too bad! Also the return of the main theme (più lento) at the end was mostly just pure esthetics and perfection, lacking all sadness and despair.

★★★

Impromptu No.4 in F minor: Allegro scherzando

Also the fourth of the Impromptus did not “fix” the situation—it again lacked signs of the composer’s tragedy, and the pianist’s permanent moderation in all aspects of drama, despair, etc. also moderated, reduced the richness in scenery in this music, and the listener’s imagination. There are some general rests in this piece (e.g., bar 164, later bars 292, 302, 309, 316, 320, or of course the two bars 488/489) which I think are truly scary moments, like a view into an abyss (there are so many of these in Schubert’s late piano sonatas!). To me, this aspect was missing from this interpretation almost completely.

Also, the eruption into parallel scales in bars 196ff were far too harmless, and later, when the composer seems to “get stuck” in repetitions—if that isn’t a sign of forlornness and despair, what is? I wish Sokolov’s interpretation had shown that aspect!

★★★

Overall Rating: ★★★

First Conclusions

To tell the truth: there were moments in these four Impromptus where I felt—bored. Some 2 hours after the beginning of the recital, it felt almost as if I had heard an evening full of the same music—the same, or at least similar emotion. I started asking myself: this is an artist who has performed many or most of the big piano pieces and concertos by Russian composers, and certainly also a far wider spectrum of classic and romantic music. Why does he restrict his recital program(s) to such a narrow scope?

Encores

Schubert: Impromptu No.4 in A♭ major, from 4 Impromptus, op.90, D.899

As first encore, Grigory Sokolov selected—another one of Schubert’s Impromptus: from the first set, the 4 Impromptus, op.90, D.899, the Impromptu No.4 in A♭ major. The annotation here is Allegretto.

Ah—some relief, at last!! This now was an absolutely marvelous interpretation, with such nice, singing cantilenas, but also the right balance of dramatic moments—and of course performed with Sokolov’s care for detail, diligent dynamics and articulation, such excellent balance, and this beautiful, single, large phrasing arch over the entire piece: thank you, Grigory, for this true highlight of the evening—maybe it was indeed worth coming to this recital?!!

★★★★★

Rameau: Les sauvages

The second encore was among the artist’s favorites, from the French late baroque composer Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683 – 1764)—a “French classic” composer. From Rameau’s Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin (1729/30) — Suite in G minor, RCT 6, Sokolov performed the popular sixth movement, “Les sauvages“.

Inevitably, the next encore had to be Rameau—performed just as Sokolov does Rameau: fast, with those rolling trills and ornaments—played with perfection, albeit really far from how this piece sounded at the composer’s time…

Schubert: Hungarian Melody in B minor, D.817

And back to Schubert with the next encore: a melody which sounds very familiar, but a piece which is not performed that often: the Hungarian Melody in B minor, D.817, with an annotation Allegretto.

A very intimate, rather restrained piece—and a dramatic contrast to Rameau. Beautiful music, in which the Hungarian character shines though in the rhythm, the modulations—and in that peculiar, curly ornament in bars 78 and 86. Beautiful—another, small highlight, indeed!

★★★★★

Rameau: Le rappel des oiseaux

I started wondering whether the selection of encores was based on spontaneous, on-the-spot decisions, or rather planned in advance: encore #4 turned back to Rameau again this time from the Pièces de clavecin (1724) — Suite in E minor, RCT 2, the equally famous and popular fifth movement, “Le rappel des oiseaux“.

A second turn towards Rameau, to a piece, cherry-picked by the pianist. See above for how I see Sokolov’s interpretation. Perfectly played also this, of course, but…

Chopin: Prélude No.15 in D♭ major, op.28/15

The fans wanted more—and so, Grigory Sokolov turned towards Frédéric Chopin (1810 – 1849). From the 24 Préludes, op.28, he selected one of the most famous pieces (and also the longest of the Préludes), the Prélude No.15 in D♭ major: Sostenuto, “Raindrop Prélude“

A piece where Sokolov must have felt “in his home turf”—a key piece already in his benchmark recording of the Chopin Préludes, op.28 from 1990. And indeed, an intense, intimate, deeply felt interpretation—and an other (last??), true highlight of the evening!

★★★★★

Debussy: 6. Des pas sur la neige, from Préludes, Book I, L.117

To conclude, Sokolov did not turn to Rameau again—though the last encore was in fact French, and yet another Prélude! Unexpectedly, he selected a composition by Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918). From the Préludes, Book I, L.117, the rather mysterious piece #6, Des pas sur la neige (Footsteps in the snow), with the annotation Triste et lent (sad and slow).

Yes, there was another encore, and one that stepped out, into an entirely different territory: first into French impressionism for style, and then, towards a really sad, desperate atmosphere, fading away into pppp and below…

Final Conclusion

The encores alone lasted over half an hour, ending the concert well over 2.5 hours after it started. To me, in the end it was the encores which “put the right spin” onto the evening, at last. Without those, I would have been really disappointed, for sure!