Yuja Wang, Lionel Bringuier / Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich

Salonen / Prokofiev / Berlioz

Tonhalle Zurich, 2014-09-11

2014-09-13 — Original posting (on Blogger)

2014-09-16 — Added links for online viewing of live recording

2014-11-03 — Re-posting as is (WordPress)

2014-12-06 — Removed links for live viewing (videos no longer available)

2015-07-04 — Added links for music scores

2016-07-24 — Brushed up for better readability

Table of Contents

Standing Ovation and a Warm Welcome for Lionel Bringuier in Zurich

The upcoming season at the Tonhalle in Zurich started with a concert on Wednesday, 2014-09-10. That concert was repeated the following day. This review is about the second one of these concerts, on Thursday, 2014-09-11.

These concerts also marked the beginning of a new era. It was the official start for Lionel Bringuier (*1986 in Nice, France) as director of the Tonhalle Orchestra.

A New Principal Conductor: Lionel Bringuier

In this position, Lionel Bringuier takes over from David Zinman (*1936). The latter has directed the orchestra for 19 years. That’s more than twice as long as any director after the first two! Friedrich Hegar (from the foundation 1868 up till 1906) and Volkmar Andreae (1906 – 1949).

Zinman has led the orchestra into a new and successful international and recording career. For him, this was the crowning of his career. For Bringuier this is the second direction after 3 years in Valladolid (Spain), and likely the first highlight in a promising career. Lionel Bringuier’s professional career started 2007 in Los Angeles: he was discovered by the director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, the Finnish conductor and composer Esa-Pekka Salonen (*1958). Salonen became Bringuier’s mentor and named him Assistant Director of his orchestra.

In 2009, Gustavo Dudamel succeeded Salonen as director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. He named Bringuier “Resident Conductor”, a position which Bringuier held up to the season 2012/13.

The Program for This Concert

The program in Bringuier’s introductory concert featured three compositions:

- Esa-Pekka Salonen: “Karawane” for choir and orchestra (premiere)

with the Zürcher Sing-Akademie (chorus master: Tim Brown) - Sergei Prokofiev: Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, op.16 with Yuja Wang, piano

- Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, op.14

The entire event was recorded for TV. The streams remained available for a couple of months, but unfortunately, the videos are no longer available.

The evening started with two brief speeches by the president of the Tonhalle Society, Martin Vollenwyder, and its new managing director, Ilona Schmiel. Thereafter, Lionel Bringuier started the concert with a second world premiere of a composition that was commissioned for this event: the composition “Karawane” was created by Bringuier’s mentor, Esa-Pekka Salonen (*1958). Salonen has accepted the newly created position of “Creative Chair” at the Tonhalle Zurich for this season.

Esa-Pekka Salonen: “Karawane”

Salonen’s two-part composition bears the title “Karawane”, for mixed choir and big orchestra (13 woodwinds, 11 brass, percussion, 2 harps, celesta, piano, strings).

The Underlying Dada Poem

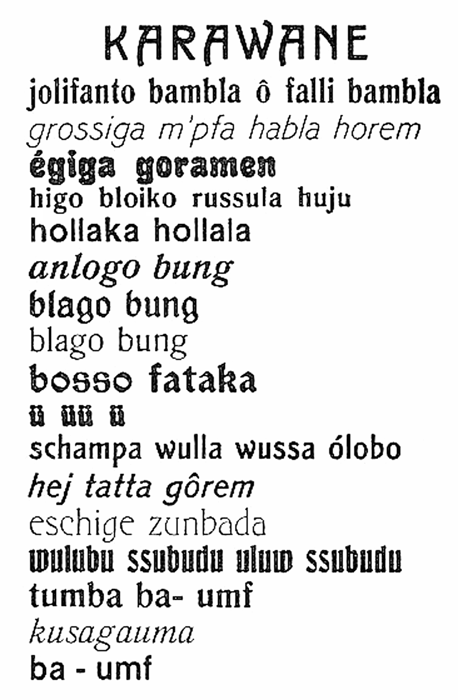

This work has close relations to the city of Zurich, which is home to the former Cabaret Voltaire, through which in 1916 the Dada movement was created. In 1917, one of its main exponents, Hugo Ball, created a poem “Karawane” (German for “caravan”, typically a trail of camels traveling through the desert), reading

The language (except for the title) is consequently free of any meaning, “deconstructed”. Yet, the text evokes pictures, such as of a trail of “Jolifants” in a circus. The 30-minute composition also relates to the Balinese “Ramayana Monkey Chant“, also known as “Kecak“.

The First Movement

Both movements of this composition start in silence. There is a signal (a deep sound) from the orchestra. Then, the choir starts murmuring / whispering by reciting arbitrary lines from the above poem, without coordination. Signals from the orchestra repeatedly stop and restart this whispering. Thereafter, the choir starts reciting the first part of the poem, supported by pizzicati from the orchestra. Singing and accompaniment broaden gradually, turn “cloudy” (Salonen).

The first part is dominated by flat, planar structures, both in sound as in harmony. The composition is not tonal. Still, one gets the feeling of a resting pole, from which the music evolves in a giant arch. It gets louder and more virtuosic, then turns into a chanted Kecak episode. After a furious build-up, the music calms down, a cello solo leads to a nightly ending and silence. There were moments in this movement when I (remotely) felt reminded of Dvořák’s music / tonalities, or of the late romantic sound worlds of Richard Strauss or Gustav Mahler. It was certainly often dissonant and loud, but (at least to me) never outlandish or irritating.

The Second Movement

The second, somewhat shorter part / movement starts similar to the first one, with whispering above resting, iridescent sounds. I felt reminded of the mysterious atmosphere in a dark, humid cave. But then, the music in both the orchestra and the choir (which is present almost all the time in this composition) rapidly picks up pace, turns more and more chaotic. Shouting, cries (Salonen: “uncontrolled, semi-chaotic circus atmosphere“) follow. After a more planar episode (“music of the spheres”? maybe alluding to Górecki or Pärt?), the music turns rhythmic again and moves into a second, longer Kecak section.

The tempo then slows down again, the music ends jubilantly, fortissimo, with the word “Karawane”. While the first movement is primarily playing with sounds and harmonies, this second part is more dominated by rhythms, and by the extended percussion group in the orchestra. Enthralling, fascinating music!

The Performance

The Tonhalle Orchestra was in top form. Lionel Bringuier obviously was thoroughly familiar with the score and the music. He didn’t show any signs of uncertainty or hesitation: an excellent start! The vocal part was carried out by the Zürcher Sing-Akademie, prepared by Tim Brown. These singers deserve high praise for this concert: excellently prepared, powerful and homogeneous voices, reliable and accurate.

The Zürcher Sing-Akademie is successfully following the footsteps of the Schweizer Kammerchor / Swiss Chamber Choir. The latter was disbanded in 2011, after losing its financial support.

The audience was enthusiastic, the applause almost frenetic. When the composer, Esa-Pekka Salonen, appeared on the podium to accept the applause, he appeared very moved by the success of the performance and of his composition. I was not surprised to notice Gustavo Dudamel, who was present in the audience throughout the concert, joining the congratulators in the artist’s room after the performance. It’s a great piece of new music that has strongly touched me and many others. I think it belongs into the top league among the compositions of the past 20 – 30 years. For this season, we are definitely looking forward to hearing more works by this composer!

Sergei Prokofiev: Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, op.16

Next in the program was the Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, op.16, by Sergei Prokofiev (1891 – 1953). Here, the Chinese pianist Yuja Wang was definitely a safe value to the programmers of the event. She is all around the media, not just because of her “fashion statements”, but primarily because of her incredibly virtuosic playing. She focuses on the most difficult, most complex pieces in piano literature, such as the concertos by Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Stravinsky and others. Just “en passant” she can pull the most intricate solo works as encores out of her sleeve (well, if she was ever wearing sleeves…).

Yuja Wang and Prokofiev’s op.16

Yuja Wang has recently released a CD with the above composition, recorded in 2013 with the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela, directed by Gustavo Dudamel. I have written about this in detail in my Blog entry “Prokofiev: Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, op.16” (where details about the recording can be found). I don’t want to repeat my notes about the artist and her performance. But still, it is worth re-iterating and expanding some of those comments in a more general context:

Preamble: a Failed Radio Comparison

Even before I had listened to the music on CD, I followed a blind comparison of 6 recent recordings of this composition on France Musique. I was more than surprised to see Yuja Wang’s recording being dismissed in the first round. The comments on the dismissal were only scarce, but devastating. I decided to take this up, making the effort (or rather: having the pleasure) to subject that recording and that of the winner in that “competition” to a more thorough and complete comparison, using the score. My conclusions are clearly pointing in the opposite direction. Yuja Wang’s interpretation offers me vastly more than that of her contender. Or of any other contender from the radio comparison. The key point is that Yuja was dismissed after only (and superficially) comparing the long cadenza in the first movement.

Also, most artists, many critics and listeners take a recording such as Jorge Bolet’s recording from 1952 as reference. One mostly hears this concerto in the style of Prokofiev’s “war sonatas” from the Stalin era: extremely percussive, mostly fortissimo and often machine-like. When I listened to Yuja Wang’s interpretation, I realized that she consciously elaborated her own approach / access to this composition. Her interpretation is much more differentiated (particularly in dynamics and articulation) than that of other artists. She is listening into the solo part, with an open ear also for the lyrical aspects in Prokofiev’s music.

Acoustic Balance on CD

On top of that, most recordings place the piano in the front and the center of the recording, which automatically favors the percussive aspects of the solo part. Yuja’s recording takes a more “integrated” (balanced, realistic) approach. Now, after that concert, I am reassured: she makes the neck-breaking piano part (often noted on three systems) sound playful and easy. But her playing can be percussive. It is so where and when needed, even if perhaps she doesn’t quite have the physical reserves of some of her contenders.

The Performance

On the part of the orchestra I can’t criticize much. Lionel Bringuier is an attentive accompanist. The orchestra was in good shape. It may be that some passages didn’t have quite the clarity and conciseness of Dudamel’s accompaniment on the CD. I’m particularly thinking of the obsessively repetitive Scherzo. That was flawless in the solo part, but perhaps at the limit of technical playability for the orchestra. Like Dudamel, Lionel Bringuier (correctly) took the Intermezzo in a heavy 4/4 pace (the score is marked pesante), rather than resorting to a faster tempo and thinking in 2/2 measures, as some other conductors do. In a harsh contrast, the tempo of the Allegro tempestoso in the last movement was absolutely breathtaking, and mastered stupendously by Yuja Wang.

I sensed that the tempi in general were very slightly faster than in the 2013 recording with Gustavo Dudamel. As expected, the audience was enthusiastic and gave Yuja Wang a long applause. Given the advanced time (1.5 hours since the beginning of the concert), there was no chance for an encore. However, for this season, Yuja Wang is “Artist in Residence” at the Tonhalle Zurich, and so we can look forward to more concerts with this artist. The next one will be on Sunday, 2014-09-14, featuring chamber music.

A Brief Note on Concert Programming

Prior to the concert, I looked at the programming of this concert and wondered why the sequence of the compositions was the opposite of their chronology in creation. My immediate thought was that the organizers intended to “get done with the difficult stuff first”. And/or, to let the concert end with a “feel well piece”, such that people would go home with a pleasant impression from the concert. Personally, I felt that a chronological order would make more sense: do the well-known, classic/romantic piece first, as people know and remember that anyway. Then have the program progress to music of the present time. This would allow for insights into the evolution of music. With the sequence given, the more familiar pieces can easily cover / obscure the impressions, the memory from music that people are not (so) familiar with.

That approach does have issues, too, in that there is a chance that parts of the audience may just leave during breaks and “skip the difficult stuff”. What fascinating music would they would have missed in this case! I have seen the opposite as well, though: a concert where people only entered the hall after the break, because they felt Rachmaninoff was too much of a challenge for them! But personally, I did not see a problem with starting with the Berlioz up to the break, do the Prokofiev after the break, and then finish off with Salonen’s piece as premiere. This would make very little difference for Yuja Wang (except that signing CDs ahead of her appearance seems illogical). However, it would give Salonen’s composition the best possible place in people’s memory!

Why the Chosen Order was Right

I felt confirmed in this opinion up to the break. But then, I had to concede that the order chosen turned out to be OK, as

- given the season opening, the speeches, and the splash that they wanted to create with the world premiere of Salonen’s piece, there were good arguments for doing that piece first. Also, one should keep in mind that when the programming was done, Salonen’s composition didn’t exist yet!

- given that this was the official introduction for Lionel Bringuier in his new position, “his” Berlioz deserved the “best place in people’s memory”. The other two performances were “owned by” Esa-Pekka Salonen and Yuja Wang.

- in the aftermath (see below), with the troubles in the opening movements, the Symphonie fantastique by Berlioz would have been a bad way to start the season.

- Finally, both “Prokofiev — intermission — Berlioz & Salonen”, or “Prokofiev & Berlioz — intermission — Salonen” would have been too unbalanced in duration. The former would have had the advantage of avoiding the need to move the concert grand in presence of the audience.

Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, op.14

With the Symphonie fantastique, op.14 by Hector Berlioz (1803 – 1869), the final part of the concert was “owned by” Lionel Bringuier and the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich. Bringuier deserved a prominent place in the program, see above. Berlioz is another “safe value” in the program, and a favorite / popular piece on the concert podium everywhere. That composition was revolutionary in many ways at the time of its creation, and yet has been popular ever since. In the Tonhalle alone, according to the program notes, it has been programmed during 38 seasons since 1903. At the same time, this composition is a virtuosic showpiece for orchestras (and conductors?) . As such, it does have its challenges: maybe it was a bit adventurous to select it for this occasion?

It could be that Bringuier felt that the orchestra is in such good shape after David Zinman’s direction that things couldn’t possibly go wrong? Well, things did go wrong. It became obvious that it will take a while for the orchestra and its new conductor to get used to each other: for the conductor to know how the orchestra reacts. But it will also take time for the orchestra to read Bringuier’s intentions while maintaining close contact between the instrumental voices. Here’s why:

Bringuier’s Personal Approach to the Symphony fantastique

Bringuier (just like Yuja Wang) does not just follow a beaten path by delivering a “standard interpretation”. He chose to present his very personal interpretation, and that proved to be risky:

- Traditional interpretations tend to use rubato-like tempo changes over several beats, often several bars. Bringuier often used brisk tempo alterations, causing serious coordination issues in the orchestra. This was a problem in the fast part of the first movement (Rêveries — Passions). It remained an issue also in the passionate part of the third movement (Scène aux champs). But it was most obvious in the second movement (Un bal). This movement is very tricky even in a “regular” performance, given its frequent tempo changes, the dance-like, swinging rubati, requiring extreme attention by all musicians.

- Bringuier tends to use fast, demanding tempi. One example is in the fourth movement (Marche au supplice), which he conducted with approx. 1/4 = 84 rather than 1/4 = 72 that Berlioz asks for in the score. The same could be said for (most of) the last movement (Songe d’une nuit du Sabbat).

- Perhaps the situation was compounded by the fact that for Salonen’s piece the podium was extended into the audience floor? This caused a deviation from the usual acoustic experience for the musicians. It possibly made it more difficult for the groups in the orchestra to maintain mutual contact?

- On top of that, the musicians may have shown signs of fatigue / partial loss of attention from the demanding pieces preceding the break?

Notes on the Performance

The result was far from ideal, to say the least. The different groups / voices in the orchestra internally remained relatively coherent, but particularly in the first movements (see above), there was often severe mis-coordination, e.g., between the cellos and the violins. I observed the same issues between the first and the second violins, even though both were placed on the left side of the podium. Also the excessively fast tempo in the last two movements proved a real challenge for the orchestra. In the end, what saved the performance partially were the brass and percussion sections. To some degree, these acted as a strong bracket (and pacemaker) that helped keeping things under control.

As a little aside: there were also slight intonation issues between the cor anglais (in the orchestra) and the oboe (playing the echo behind the scenes) at the beginning of the third movement. Finally, to me, the breaks between some of the movements were too long. In particular, movement 4 (Marche au supplice) should in my opinion follow the preceding one almost attacca. Otherwise, the threatening rumbling at the end of that third movement makes little sense. However, from all the coughing and other noise during those breaks I sensed that also the audience started to lose focus / attention towards the end of the concert, requiring these breaks.

Conclusion, Summary

Was it forgiveness, tolerance, relief or generosity (I hope it wasn’t ignorance!) that the audience still gave the conductor and the orchestra a standing ovation (and hence a warm welcome to Lionel Bringuier in his new position)? He must have sensed what happened, but there may not have been enough time for him to realize his intent during the preparations. Also, he was probably not able or willing to consider resorting to a safe (“08/15”) version. Who would have wanted this, anyway? This was a mishap, and we should not condemn our new conductor for this. He deserves a chance and sufficient time to develop and realize his own visions. Plus: the first half of the concert, especially “Karawane” has demonstrated that he does have the potential that both the audience and the orchestra are hoping for!

Addendum 1

For some works in this concert, scores are available:

- Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, op.16 is available as study score (10.25″ x 7.25″ / 26 x 18.4 cm) —Find score on amazon.com (#ad) —

Addendum 2

For two of the compositions I have compared selected recordings in separate Blog posts:

- Prokofiev: Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, op.16 (this includes the recording with Yuja Wang and Gustavo Dudamel)

- Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, op.14

Initially, I hesitated writing about the coordination issues in the orchestra in the Symphonie fantastique, considering the somewhat distorted acoustics from my seat in the first row. I was almost “under” the cello section. In the online booking I selected row 6, as the first 5 rows were all shown as “booked”. There was no mention that these were actually taken up by the podium! Still, from others in the audience (I saved reading other reviews till after this posting is published), I sensed that my concert impressions were correct.

Addendum 3

The entire concert has been recorded, and all three compositions in this concert can (could) be viewed online:

- Salonen: “Karawane” (32’41” — video no longer available)

- Prokofiev: Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, op.16 (34’02” — video no longer available)

- Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, op.14 (51’41” — video no longer available)