Riccardo Chailly / Lucerne Festival Orchestra

Wagner / Bruckner

KKL, Lucerne Festival, 2018-08-25

2018-09-04 — Original posting

Bruckner als Wagners Adept? Mitnichten! Riccardo Chailly und das LFO am Lucerne Festival — Zusammenfassung

Nach dem begeisternden Ravel-Abend am Vortag boten Riccardo Chailly und das Lucerne Festival Orchestra auch bei Wagners Ouvertüren zu “Rienzi” und zu “Der fliegende Holländer”, sowie in Bruckners Sinfonie Nr.7 in E-dur Hervorragendes.

Table of Contents

Introduction

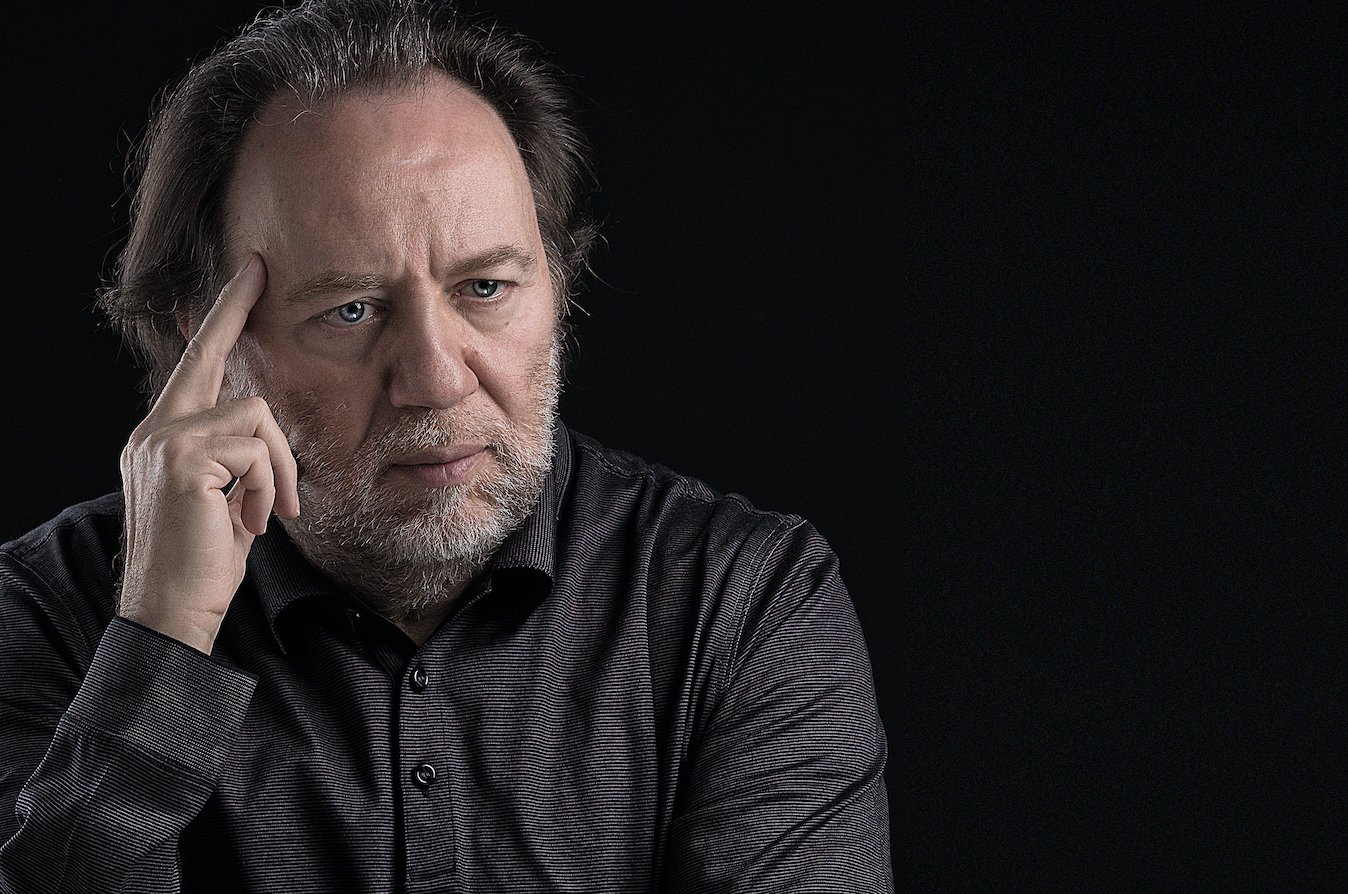

Just one day after a fabulous evening with an all-Ravel program at this year’s Lucerne Festival, the Lucerne Festival Orchestra was once more on the podium of the KKL (Lucerne Culture and Congress Centre). And again, it played under the direction of its chief conductor, Riccardo Chailly (*1953). Chailly is an Italian conductor who started his career under the auspices of the late Claudio Abbado (1933 – 2014). Initially, he was focusing on opera, but then gradually expanded his scope into the symphonic repertoire. In August 2015, he started in the position of Chief Conductor of the Lucerne Festival Orchestra. See also my review of the Ravel concert for more information.

Venue & Acoustics

The venue was the (great) White Hall of the KKL, with its highly rated acoustics. The venue was sold out in this concert. I noted that the echo chambers near the ceiling were essentially all open, so I expected (and indeed noted) an acoustic environment with perceptible reverberation. This was certainly adequate for Wagner’s overtures, even ideal for the Bruckner symphony. I didn’t check the echo chamber openings in the preceding concerts, but I’m certain that for Ravel, the acoustic setting was more analytic (less reverberation).

I had a stall seat in row 21 (middle of the rear block, just behind the top category), close to the middle axis.

The Program

With this program, Chailly went back from Ravel’s music into the 19th century, to Bruckner’s Symphony No.7. As this does not fill an evening, Chailly added two early overtures by Richard Wagner. The latter is a composer that Anton Bruckner not only kept in high respect, but deeply venerated, idolized. In many ways, Bruckner even imitated features in Wagner’s music. With this, it really made sense to combine Wagner and Bruckner in this program:

- Wagner: Overture to the Opera “Rienzi, der letze der Tribunen“, WWV 49

- Wagner: Overture to the Opera “Der fliegende Holländer“, WWV 63

(Intermission) - Bruckner: Symphony No.7 in E major, WAB 107

Bruckner — A Wagner Adept?

From the relation between the two composers (even though that relation was essentially unilateral), the program seemed logical. However, almost certainly, neither “Rienzi” nor the “Flying Dutchman”—both early works—were the operas that Bruckner was referring to when thinking about Wagner. On top of that, Bruckner was anything but a mere Wagner epigone. He was impressed and influenced by harmonic and instrumentation features in Wagner’s operas (more on that below). However, his symphonic forms surpassed anything that Wagner has ever created in that area.

In that sense, a confrontation of the composers is unfair, especially if the primordial forces in Bruckner’s mature symphonies are placed next to two early overtures by Wagner. Even more so, as the performance presented these overtures outside of the context of their respective operas.

Wagner and Bruckner after Ravel

However, the contrast between the above program and the Ravel-only program on the preceding day was even much stronger. Neither Wagner not Bruckner can compete in any way with Ravel’s extreme refinement in dynamics and instrumentation, his richness in colors and atmosphere. That confrontation may be inadequate—though, whoever attended both concerts can’t just forget about the impressions from the first one. Yes, the two programs weren’t comparable, were even incommensurable, i.e., couldn’t possibly have been more different. Nevertheless: maybe it would have been better to swap the two programs?

Indeed, in view of the vivid memory from the Ravel-evening, the beginning of this concert with Wagner’s “Rienzi” overture felt like (and was, of course) a descent, if not a hard fall into an older era. This does not imply a lower quality in the performance, and by no means do I want to belittle the merits of either Wagner of Bruckner as composers. Naturally, neither of the two disposed of Ravel’s possibilities and experience in advanced instrumentation. On top of that, their aim was not the ultimate refinement in expression. Nor was it Ravel’s intricate, sophisticated play with dynamics and colors. Their strengths and preferences were in completely other areas.

Concert & Review

Wagner: Overture to the Opera “Rienzi, der letze der Tribunen“, WWV 49

Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883) began working on his early opera “Rienzi, der Letze der Tribunen” (Rienzi, the Last of the Tribunes), WWV 49, in 1837. It became his third completed opera, based on a libretto that he wrote himself. The opera premiered in Dresden, 1842, with some cuts. Here already, the composer was aiming for gigantism. He wanted to surpass every existing opera—in all aspects, most notably those by Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791 – 1864).

The excessive proportions of the opera (for that time), and the exorbitant staging may also have been the result of the composer trying to get out of a major, personal financial fiasco. However, the opera with its five acts is so big that it never was performed in its entirety. At one point, the composer split the score of the four-hour work into two parts. Versions of the composition had some popularity for a few decades, but Wagner himself didn’t like his creation in the end. The original form of the opera is lost, as the only source of the full version, Wagner’s manuscript, was given to Hitler (who allegedly demanded it), and thereafter it disappeared. The one part which retained some popularity is the overture.

The Sound of the Music

Musically / harmonically, the score is still oriented on models such as Gaetano Donizetti (1797 – 1848), Gioacchino Rossini (1792 – 1868), Giacomo Meyerbeer and other contemporaries. I even noted elements that resembled the musical language of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809 – 1847). In contrast to Ravel’s music from the day before, this was far less the hour of the (wind) soloists in the orchestra: Wagner didn’t use Ravel’s refined musical syntax. Rather, this felt like a picture from broad(er) brushstrokes. With this, the focus in the orchestra was far less in the performance of soloists in a large variety of small combinations (especially wind instruments). Here, the focus was on homogeneity of sound, musical expression in bigger instrument formation, such as the brass section.

The Performance

One may find it regrettable that the orchestra didn’t get an opportunity to play out all its strengths (especially those required for Ravel’s music). Nevertheless, it—expectedly—was excellent also with Wagner’s music. Under Chailly’s direction, the articulation in the strings was consciously mellow, romantic, with warm sound and a generous amount of portamento in slow melodies. There was also the perception of a load of (initially restrained) power. There was one minor mishap at the beginning. For the first two, highly exposed bars, the intonation in the woodwinds wasn’t 100% clean. However, this was a singular incident that did not affect the overall picture at all.

Now, different again from Ravel’s music, within the sound of the ensemble, the strings played a much more prominent role. This also explains why the concertmaster (Raphael Christ) contributed more actively than in the preceding concert. Moreover: it was really refreshing to see how the entire orchestra, especially the musicians in the violin sections (many of them concertmasters and lead artists from first desks) participated very actively, motivated and with utter attention. With the help of Riccardo Chailly’s sense for dramatic development, for big forms, the orchestra presented a compelling, convincing performance.

Rating: ★★★★

Wagner: Overture to the Opera “Der fliegende Holländer“, WWV 63

Wagner’s opera “Der fliegende Holländer” (The Flying Dutchman), WWV 63, premiered one year after “Rienzi“, in 1843, again in Dresden, and again under the direction of the composer. With this work, Wagner made considerable progress towards detaching himself from the composition style, the harmonic pattern of his contemporaries, working towards his personal musical language.

The Performance

More than the overture to “Rienzi“, the one to “The Flying Dutchman” features big thematic gestures, especially with the gigantic, towering waves at sea, or also later, when the piece anticipates, depicts the emotional drama in the opera. On the other hand, there are indeed also (a few) intimate moments, in which the woodwinds can play out their strengths. However, besides the impressive, rolling waves, the key change between the two overtures is in the overall dramatic development. It was excellent how Chailly realized the consequent, compelling dramatic “pull” towards the dramatic climax.

Two Overtures?

Overtures typically follow the course of action in the subsequent stage work, hence don‘t necessarily feature a “closed, self-contained” form. This did not affect the two overtures here. In “Rienzi“, Wagner uses the trick of thematic anticipation to achieve a coherent form, and the overture to “The Flying Dutchman” appears circular, consistent through the recurring theme of the rolling waves. Yet, in both cases, the absence of the associated opera left the impression of something fragmentary: the preparation for the subsequent drama, the promise of an action to follow saw no fulfillment, ran into a void.

With one overture, a subsequent concerto or symphony can act as substitute for the stage work. However, here, another overture (without thematic connection to the first one) followed just prior to the intermission, and that definitely left the impression of incompleteness. Also, looking beyond the intermission: the subsequent Bruckner symphony didn‘t do anything to alleviate that incompleteness. Apart from Bruckner‘s admiration for Wagner, there is nothing that links the symphony to these two overtures.

Rating: ★★★★

Bruckner: Symphony No.7 in E major, WAB 107

Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1896) composed 11 symphonies, among them one early study, another early work (“No.0”), and the last, No.9, with an incomplete finale. The Symphony No.7 in E major, WAB 107, is among the best-known of these works. Bruckner wrote it 1881 – 1883, the final revision was completed 1885. The symphony features the usual four movements:

- Allegro moderato

- Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam (Very solemn and very slow)

- Scherzo: Sehr schnell (Very fast) — Trio: Etwas langsamer (Somewhat slower)

- Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht schnell (Moving, but not fast)

Cross-Links to Wagner?

Yes, Bruckner adored, admired Wagner almost religiously. However, that picture is misleading, given the extreme differences between the two characters. I can‘t discuss this here in detail, but let me state that much: Wagner‘s declared goal was, to create something new, unheard of, bigger, more comprehensive and all-encompassing than anything that existed in terms of stage works.

Bruckner looked up to Wagner as an idol. He admired many of the features in Wagner‘s works. And he adopted features from Wagner‘s music, such as instrumentation, harmonies, elements of themes. At the same time, he desperately was looking for recognition as composer and musician.

However, beyond that, Bruckner was far less of a proactive, ambitious composer / creator. Rather, when I‘m thinking of Bruckner, I picture a man in whose creative mind, his monumental symphonies spontaneously erupt, break in with the overwhelming power of primordial forces. The many versions of his symphonies give testimony of the composer’s nerve-wrecking effort to cast these inspirations into the giant structures of his symphony movements. Sometimes, the composer‘s struggles can still be felt through the final version. In this symphony, I think it is primarily the last movement which still shows this.

The Performance

For this symphony, the two concertmasters at the first violin desk swapped position: here, Gregory Ahss was now assisting Riccardo Chailly in the leadership, primarily for the string section. The orchestra exhibited an excellent, warm and homogeneous string sound. Only early in the first movement, there was a moment where there was a slight discrepancy in the violin voices. That was a momentary and minor incident, thereafter the string voices were coherent, left very little, if anything to wish for.

I. Allegro moderato

Width is needed here! For one, width in dynamics, from a whispered ppp up to generous, powerful sound eruptions. At the same time, this symphony also requires a very long “mental breath” in melodies and phrasing. A prime example for the latter is the “endless, divine” melody at the beginning of the symphony, and similarly, the giant, intensifying, build-up waves, picking up more intensity and power, up to the overwhelming climax. This clearly was the hour of the excellent brass section, precise, sharp in the often virtuosic fanfares! But the strings were shining equally. Not just the violins, actually: already in the first segment, viola and cello were singing that beautiful melody. Later, around “I” in the score (bars 185ff.), the cello shone in another, very nice, melancholic cantilena.

Chailly supported the phrasing with a proper, natural amount of agogics, and at the top of the build-up waves, the orchestra sound was very powerful. It never overloaded the acoustics, though, the orchestra always remained controlled in its dynamics, keeping the balance. I also liked how the musicians throughout the ensemble paid attention to details in the articulation.

II. Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam

The two overtures did not feature any “Wagner tubas” (tenor and bass tubas in B♭ and F): they weren’t invented yet at that time. However, here they were, four of them! Hearing their very peculiar, slightly covered timbre (greetings from “Siegfried’s Death and Funeral March“!), prevailing already in the first bars, made this a very special moment! Really, that hymn did have something of a funeral march. This is then carried further by the strings, then turns into a comforting, beautiful melody. This only lasts up to the next “cry for help”, followed by the Wagner tubas again, now painfully dissonant. The movement alternates between despair / mourning and comforting, even hopeful atmosphere. Even though it returns to the initial funeral music, it is really touching, moving, highly expressive music!

Riccardo Chailly is excellent at managing that big, huge breath, the calm atmosphere. And never, ever he dropped the tension: not in long ppp passages, nor in the critical general rests. He had the oversight over the large arches, followed Bruckner’s large structures, and kept the tempo in control. Also here, the orchestra produced an impressive, nearly overwhelming (but never excessive) climaxes. Naturally, in the latter, the brass and percussion voices prevailed, with stellar sound. The end returns to the horns and Wagner tubas, to the beginning, in a way. However, remarkably, the music didn’t seem to indicate whether it depicted despair, consolation, or even hope: the movement ended with a question mark (and expectations about the movements that followed). Food for thought!

III. Scherzo: Sehr schnell — Trio: Etwas langsamer

More than the other movement, in the Scherzo build-up waves are a dominating element: twice, it starts fast, motoric, but pp, then builds up to an “angry splash”. It seemed carried by full involvement, even enthusiasm, of every musician in the orchestra. The general rests after each of the “final bangs” gave a good impression about the amount of reverberation in the White Hall: here and in the last movement in particular, I had the feeling that the acoustics were really optimized (and optimal) for this music.

Interesting: even though the tempo annotation is “somewhat slower”. This felt like an entirely different world: the motorics of the Scherzo were gone, which opened space for a gentle scene. Yet, Chailly kept a latent tension, took the Trio through a build-up into tamed climax, before the Scherzo returned.

IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht schnell

Build-up waves are present here as well, so typical for this composer. However, this movement seems more heterogeneous than the others. As indicated above, I feel that the last movement gives the clearest indication about Bruckner’s struggle with getting the music into its “final” form. That does not affect the listener’s experience, though. Particularly not in this performance. Chailly presented a compelling tempo concept, with a feel for the “right” pace. In this performance, the movement was full of galvanic suspense (but never pushed) in the softer segments, the fanfare-like climaxes almost bursting from all the brass power.

A final word on the orchestra’s performance: it was masterful, from the strings to the woodwinds (the solo flute, Jacques Zoon, in particular was excellent!), on to the entire brass section. One can’t ignore the timpanist, Raymond Curfs, whose impressive, almost endless crescendo drum rolls at the end of every movement (except for the Adagio) earned him a special applause.

Rating: ★★★★½

Conclusion

The applause was long and enduring, though not a spontaneous, standing ovation as the night before. Chailly again honored his musicians by accepting the applause from between the first desks. However, it was quite telling that the orchestra vividly applauded its chief conductor, even started trampling.

In terms of performance quality, this concert was excellent. It wasn’t much, if anything, behind that of the Ravel-concert. My rating is slightly below, however: I’m rating the concert experience, not just the quality of the performance. Therefore, the choice of repertoire plays a role, too. Plus, I can’t simply ignore the brilliant experience from the night before.

Addendum

For this concert I have also written a (shorter) review in German for Bachtrack.com. This posting is not a translation of the Bachtrack review, the rights of which remain with Bachtrack.com. I created the German review using a subset of the notes taken during this concert. I wanted to enable my non-German speaking readers to read about my concert experience as well. Therefore, I have taken my original notes as a loose basis for this separate posting. I’m including additional material that is not present in the Bachtrack review.