Georg Philipp Telemann: 12 Fantasias for Flute

Media Review / Comparison

2014-01-18 — Original posting (on Blogger)

2014-11-10 — Re-posting as is (WordPress)

2016-07-16 — Brushed up for better readability

Table of Contents

Introduction — Collecting Recorder Recordings

A recent visit to a recorder maker led to the addition of Dorothee Oberlinger‘s recording of the Twelve Fantasias for Transverse Flute without Bass, TWV 40:2-13 by Georg Philipp Telemann (1681 – 1767) to my existing, small collection.

I used to have one recording of these Fantasias on LP, played by Maxence Larrieu (Tudor 73013, ℗ / © 1975), played on a modern Böhm flute, of course. I have not listened to that recording in decades. And now I don’t even have the equipment set up to listen to LPs. It is certainly a good recording for its time: Maxence Larrieu is a brilliant flutist whom I also knew from other recordings. However, when I started collecting CDs in the 90s, I was rather looking for a historically more informed version and selected the recording on historic transverse flute (traverso / flauto traverso) played by Barthold Kuijken shown below. I later added a recording with Dan Laurin, playing on recorder, later another one with François Leleux playing oboe.

Finally, more out of curiosity, I added a recording played by Kevin Thompson on a euphonium — for the sole reason that our son is/was playing that instrument. Apart from that, individual Telemann Fantasias are present in two additional recordings with mixed repertoire shown below, both played on recorders, by Maurice Steger and Leif Ramløv Svendsen. These are the recordings that I discuss in this post. At this point, I’m not really motivated to revisit the recording on modern Böhm flute by Maxence Larrieu, or any other recordings on modern instruments.

The Recordings in this Review

Telemann — Barthold Kuijken

Telemann: The twelve Fantasias for Transverse Flute without Bass

Barthold Kuijken, flauto traverso

Accent ACC 57803 (CD, stereo); ℗ 1978

Telemann / J.S. Bach / C.P.E. Bach — Laurin

Telemann: Twelve Fantasias; J.S. Bach: Solo, BWV 1013; C.P.E. Bach: Sonata, Wq.132

Dan Laurin, recorder

BIS-CD-675 (2 CDs, stereo); ℗ / © 1994

Die Blockflöte im Barock — Leif Ramløv Svendsen

Die Blockflöte im Barock

Compositions by F.Barsanti, G.Ph.Telemann, J.B.Loeillet de Gant, J.M.Leclair

Leif Ramløv Svendsen, recorder

Mogens Rasmussen, viols; Viggo Mangor, archlute; Allan Rasmussen, harpsichord

claves CD 50-2112 (2 CDs, stereo); ℗ / © 2001

(currently not available)

Telemann — Maurice Steger

Telemann: Solos & Trios

Maurice Steger, recorder

Continuo Consort Naoki Kitaya

claves CD 50-2112 (2 CDs, stereo); ℗ / © 2001

Telemann — Dorothee Oberlinger

Telemann: 12 Fantasias

Dorothee Oberlinger, recorder

Deutsche harmonia mundi 88765445162 (CD, stereo); ℗ / © 2013

Not discussed / reviewed in detail:

Telemann — Héloïse Gaillard

Telemann: 12 Fantaisies

Héloïse Gaillard, recorders

agOgique AGO014 (CD, stereo); © 2013

Telemann — François Leleux (oboe)

Telemann: Douze Fantasies pour Hautbois

François Leleux, baroque oboe

Syrius SYR 141318 / iTunes download (128 kbps, stereo); ℗ 2006

Telemann — Kevin Thompson (euphonium)

Telemann: Fantasias

Kevin Thompson, euphonium

iTunes download (128 kbps, stereo); ℗ 2005

Notes on Telemann’s Fantasias

On the structure

Telemann’s Fantasias are structured individually, with the number of movements varying from two (#1, #7) to three or four (#2, #9, #11), whereby some of the movements are further structured:

- slow — fast (mvt.1 in #7; mvt.1&2 in #12)

- slow — fast — slow (mvt.1 in #3)

- fast — slow — fast — slow (mvt.1 in #5)

Musical Language

All Fantasias are true virtuoso pieces. They are demanding & difficult in the fast movements (especially on a transverse flute that does not respond as quickly and instantaneously as, say, an oboe). Additional demands stem from their long phrases (no breathing pauses) and wide tonal range. In addition, most or all Fantasias have sections with hidden polyphony, where the flutist is imitating two (or more) voices by constantly jumping between the two voices. This results in frequent, wide jumps (typically more than an octave), which are very demanding (at least on some of the instruments presented here). That demand is in the fingering, but also in the articulation, particularly if the two voices are to be heard independently and should consist of well-formed notes (rather than just short staccato “blobs” with a vague pitch).

Repeats

In the Fantasias #1, #2, #3, #4, #5, #8, and #11, the last movement consists of two parts with repeat signs (AABB); in the Fantasias #6 and #7 this applies to the first movement. The first movement in #7 is a French Overture in AA’BB’ form. In Fantasias #9 and #10 both the first and the last movement are in AABB form; the last movement in #12 consists of six sections, all with repeat signs (AABBCCDDAABB). Not all artists perform all repeats as noted in the score, see below (hence the two duration columns in the table above). Often, the first repeat is performed, the second repeat omitted (in analogy to a repeated exposition in a sonata movement).

Notation

The available notation is based on a print of the first edition, now stored in the Royal Conservatory in Brussels. This was published by Telemann himself. The score can therefore be considered authentic and correct (with the usual few “typos”). Telemann has meticulously added slurs, staccato (or détaché), p and f markings where he definitely wanted notes to be played as indicated. But that’s just in key locations: there are wide spreads almost lacking any indication about articulation. There, the artist must make his/her own decisions about phrasing, how to structure the text / melodies, etc.

Ornamenting

As often in baroque times, essential ornaments (e.g., mordent, appoggiatura) are fully written out (in this score, trills are marked with “+”). But almost certainly, a contemporary virtuoso would have added his/her own ornaments, e.g.:

- altering the second instance of a melody (fragment);

- adding ornaments in repeat sections (the first instance is typically left more or less untouched);

- slow transition segments consisting of only very long notes are often (if not even typically) “filled” with free cadenzas.

Comparison — Timing

The above CDs include recordings of the 12 Fantasias for Transverse Flute without Bass by Georg Philipp Telemann (1681 – 1767). One CD is with the instrument these pieces were written for. The others feature alternative instruments (mostly recorder, see below). Five of the seven recordings cover the entire set of 12 Fantasias.

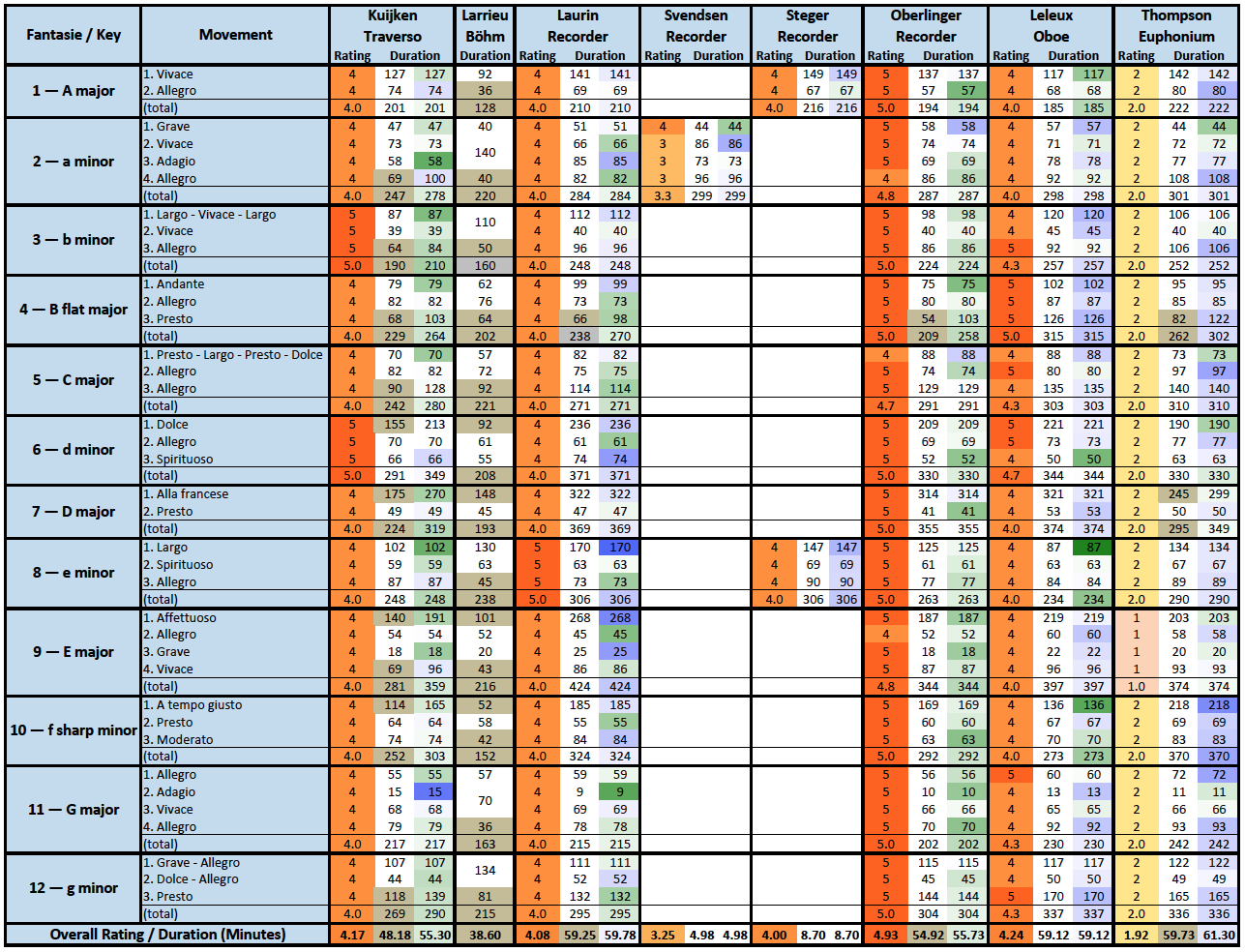

Comparison Table — Rating and Timing

Here’s a summary table giving my (subjective) ratings. The durations are in seconds, except for the last row, showing the overall duration in minutes. I made two columns for the duration of each track. The left column is the actual time. Colored fields indicate (a) missing repeat(s). The colors in the second duration columns indicate shorter (faster) and longer (slower) interpretations. The values in these second duration columns reflect the inclusion of all repeats.

The column for Maxence Larrieu (Böhm flute, times from the LP cover) is added just for reference — I have not checked exactly which repeats are performed. Most likely, he did not perform any repeats at all.

The above table (click for a full-size view) shows my ratings. For those CDs using one track per Fantasia (Barthold Kuijken, Dan Laurin, Kevin Thompson), the rating for that track was assumed to apply to all movements of the given Fantasia.

Remarks on the Recordings

Barthold Kuijken, Traverso

Instrument

This is the only recording (in my collection) played on the instrument for which these compositions were written — the (flauto) traverso or flûte traversière (transverse flute). Barthold Kuijken recorded the Fantasias back in 1978. He played a very nice historic instrument, built by G.A. Rottenburgh, ca. 1740, with excellent, balanced sound. The instrument appears to be tuned to approximately a’ = 405 Hz (almost a quarter note below baroque tuning with a’ = 415 Hz). Kuijken plays all twelve Fantasias in the original key:

- #1: A major

- #2: A minor

- #3: B minor

- #4: B♭ major

- #5: C major

- #6: D minor

- #7: D major

- #8: E minor

- #9: E major

- #10: F♯ minor

- #11: G major

- #12: G minor

I consider this a very nice recording. It’s beautifully played in tempo, phrasing and articulation, virtuosic, with very little vibrato, on an excellent instrument with soft, often ethereal tone (sometimes close to the sound of a glass harp!). Kuijken plays with very good intonation, with a lot of breath for long phrases (or the breathing is kept hidden / unnoticeable!).

Tempo

Kuijken’s tempi are close to average, some are slightly faster, especially slow movements. This may be dictated by breathing requirements. Few movements are slightly slower than most other interpretations in this comparison (i.e., slower than with other instruments). These are typically fast movements where the transverse flute has limitations (e.g., in how rapidly one can repeat a single note). The Adagio in Fantasia #11 appears much slower, but that is due to the addition of a free cadenza.

Repeats

The treatment of repeats is somewhat inconsequent: in #1, #8, and #11 all repeats are performed, in #12, two of the 6 repeats are omitted (AABBCCDAAB). In all other Fantasias, the second repeat is omitted.

Ornamenting

Kuijken uses moderate ornamenting in repeat sections, sometimes also in recurring elements, such as the second largo in Fantasia #3. Of course, one needs to consider that this recording is now 35 years old. I suspect that Kuijken now would add more ornaments.

Conclusion, Rating

I’m tempted to declare this a reference recording. However, I can’t really say that because it is the only recording in my collection using the instrument the Fantasias have been written for. This also explains why I hesitated giving a top rating throughout.

In any case, it is an excellent recording, recommended.

Dan Laurin, Recorder

This double-CD was recorded in 1994. Besides the Telemann Fantasias, it also includes a bonus CD with J.S. Bach’s “Partita for Flute solo in A minor”, BWV 1013 (ca. 20′, discussed in a separate blog posting). There is also Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach‘s “Sonata per il Flauto traverso solo senza Basso”, Wq.132 (ca. 13’40” — a very nice, short sonata with three movements Poco adagio — Allegro — Allegro; the remarks below equally apply to the pieces on the bonus CD).

Instrument(s)

Dan Laurin (*1960) plays all Telemann Fantasias (as well as the pieces on the bonus CD) on two voice flutes in d’ (a = 415 Hz), built by the late Frederick Morgan (Daylesford, Australia, 1940 – 1999), after models by Peter I. Bressan. These are beautiful instruments (some would say they are the best one could get), with a very warm, well-balanced, full tone over the entire range (the listener can’t tell them apart). They allow the artist to play all Fantasias in their original key (see above). Unlike Dorothee Oberlinger, Laurin uses only one type of recorder. I suspect that this wasn’t just done to retain the original keys in these pieces, but also to retain a sound that is as close to the transverse flute as possible. Indeed, Laurin’s and Kuijken’s recordings are often very close in their sound and articulation.

Articulation

Initially, I made the mistake of listening to Dorothee Oberlinger (see below) first. In this case, Laurin’s interpretation sounds a bit “flat”, given Oberlinger’s extremely detailed and vivid articulation. This picture is deceptive, though: Laurin uses decent agogics and careful phrasing, his articulation is slightly broader, with a tendency towards legato, avoiding super-“sharp” staccati or percussive articulation. He mostly uses moderate tempi.

In few movements (the Adagio in #2, the Spirituoso in #6, the Largo in #8, both slow movements in #9) he is the slowest in this comparison. These are deliberate choices, allowing Laurin to play out the real strength of his instruments, their beautiful tone! Laurin would not select a tempo that prevents to let each note retain its full sound, especially in those passages with hidden polyphony, jumping between high and low extremes (especially the lower line is played with carefully articulated notes).

Intonation

At this point, I should add a short note on intonation: period recorders and their (proper) replicas use anything but equal temperament tuning. Period recorders essentially use mean tone tuning: several “enharmonic pairs”, e.g., C#/Db, D#/Eb, G#/Ab (on a recorder in C) can be played with specific fingerings for the “#” and its “b” counterpart, respectively; in addition, the artist can modulate the pitch within certain limits. To me, one striking demonstration of the recorder’s “non-equal temperament tuning” is in the (partial) falling chromatic scales in the Largo in Fantasia #8. It is a joy to hear how every half tone interval in these scales is different!

Ornaments

Laurin is mostly moderate in adding ornaments. He does take the opportunity of recurring bars (e.g., the second largo section in the first movement of Fantasia #3) to play a short cadenza / fioritura. In movements with repeats, Laurin predominantly (but not exclusively) adds ornaments in the second pass only. Occasionally (e.g., in the first movement of Fantasia #4) he fills wide jumps with broken chords. This affects the separation between the two voices, i.e., it obscures the polyphony. There are also a few movements where Laurin is noticeably faster than the others, e.g., the fast movements in #2, the final movements in #4, #5, #8, and #12, the Allegro in #6 and #9, the Presto in #10. Occasionally (e.g., the Presto in #4), this causes him to be slightly superficial in the semiquavers.

Repeats

With the one exception of the second repeat in the Presto in Fantasia #4, Laurin plays all (first & second) repeats.

Conclusion, Rating

Overall, an excellent recording, especially for the sound of Fred Morgan’s recorders.

For more information on Frederick Morgan: there’s a very nice and informative memorial book “Blockflöten nach historischen Vorbildern — Fred Morgan, Texte und Erinnerungen, zusammengestellt von Gisela Rothe”, published by Conrad Mollenhauer GmbH, Fulda, 2007, 205pp. (ISBN 978-3-00-021216-1).

Leif Ramløv Svendsen, Recorder

This CD with recorder music by various composers dates from 2000. For a general discussion see the Listening Diary 2013-12-21. The CD only features one single Fantasia, No.2 in A minor — here in transposition:

- Fantasia 2: A minor, transposed to D minor (tenor recorder in c’)

The instrument is a tenor recorder in c’ (a’ = 415 Hz) made by Heinz Ammann, Wollerau, Switzerland. It features a warm, dark (yet very slightly “grainy”, structured) sound. The interpretation is definitely not the best in this comparison: the articulation is often somewhat coarse, the phrasing somewhat rigid, lacking flexibility & agogics. The first movement (Grave) is an exception: the tempo could be slower, the starting motif with its four crotchets is rather stiff and static, but I quite like the jeu inégal in the semiquaver passage.

The second movement is a bit too slow for a Vivace. In the following Adagio I don’t see why the first three sextuplets should be shortened, almost as if this was a French Overture with double punctuation. Throughout first part, the rhythm is totally unclear. In the last movement, I don’t like the articulation of some of the quavers — they often sound as if played with a slow flattement. The last movement is performed with both repeats.

Maurice Steger, Recorder

In 2001, Maurice Steger (*1971) recorded a CD devoted to music by Telemann, including the following two Fantasias, in the original key:

- Fantasia 1: A major (voice flute in d’)

- Fantasia 8: E minor (voice flute in d’)

Instrument(s)

The recorder for Fantasia #1 was by Adrian Brown (Netherlands), after a model by Jacob Denner. The recorder for Fantasia #8 was by Frederick Morgan (Daylesford, Australia), after models by Peter Bressan and Thomas Stanesby.

In Fantasia #8, Maurice Steger uses a recorder from the same workshop as Dan Laurin, but apparently not quite the same model. In fact, it’s a model that combines designs from two historic instruments. The instrument sounds much smoother than Laurin’s.

Interpretation, Tempo

Among all artists discussed here, Steger takes the most freedom in reading the score. He presents the most extreme interpretation, especially in Fantasia #1, with extreme agogics, stretto passages (without indication in the notes, of course), tempo jumps, extremely rapid figurations and ornaments, sudden breaks/halts, especially for detached closing notes — playing jokes, sort of: one can easily visualize how he is bending his body in all directions in these passages! In this Fantasia, clearly, the focus is on virtuosity and fun, rather than showing off the tone of his recorder.

Tempo

Steger’s tempo in the first movement is between that of Laurin and Oberlinger. In the last movement, he is slower than the others (1/4 = 105): if the text is read as 3/4 measures, this is rather slow for an Allegro. However, the movement rather feels like an intricately syncopated 6/8 rhythm, i.e., running in two 3/8 beats (3/8 = 70), which really makes this feel even slower. Also, not even Laurin’s faster tempo, 1/4 = 126 or 3/8 = 84 really makes this sound like an Allegro.

Recording

The microphone placement is very close to the recorder, apparently. Steger’s breathing may be too audible to some listeners. It sometimes sounds as if he were momentarily sucking condensed liquid out of the wind channel. Also, one can frequently hear Steger’s “percussive fingering” (a hollow wooden “bang”, often with a defined pitch) — an effect that modern composers may use explicitly. The breathing may be viewed as too prominent, but overall I prefer realistic / “artisanal” recordings over polished, neutral / sterile ones. In a concert hall, these noises will typically not project very far.

Conclusion, Rating

Another excellent interpretation with focus on virtuosity and fun — just covering two of the Fantasias, unfortunately. For brief comments on the other pieces by Telemann on this CD see the notes at the bottom of this posting.

Dorothee Oberlinger, Recorder

Recording, Instruments

Dorothee Oberlinger’s recording of the Telemann Fantasias is the newest in my collection. It was made in 2013. In this recording, five of the Fantasias are transposed, and a mix of recorders (voice flute and alto recorders) is used. Here’s what the liner notes state:

- #1: A major (voice flute)

- #2: A minor (voice flute)

- #3: B minor, transposed to D minor (alto recorder)

- #4: B♭ major, transposed to E♭ major (alto recorder)

- #5: C major (voice flute)

- #6: D minor (voice flute)

- #7: D major, transposed to F major (alto recorder)

- #8: E minor (voice flute)

- #9: E major (voice flute)

- #10: F♯ minor (voice flute)

- #11: G major, transposed to C major (alto recorder)

- #12: G minor, transposed to A minor (voice flute)

A Correction to the Liner Notes

There is also the list of instruments in use, all alto recorders:

- f’ (a’ = 415 Hz) after Denner, by Ernst Meyer dit le Bec, Paris, 2008

- g’ (a’ = 415 Hz) after historical models, by Fumitaka Saito, Amsterdam, 1999

- f’ (a’ = 415 Hz) after Bressan, by Ernst Meyer dit le Bec, Paris, 2008

- g’ (a’ = 415 Hz) after Bressan, by Frederick Morgan, Daylesford, 1998

Unfortunately, this can’t be right, as no voice flute (in d’) is mentioned. A well-known historic model for voice flutes is by Bressan (also Dan Laurin and Maurice Steger play voice flutes after Bressan). Therefore, I suspect that the bottom two lines in the above list should read

- Voice flute in d’ (a’ = 415 Hz) after Bressan, by Ernst Meyer dit le Bec, Paris, 2008

- Voice flute in d’ (a’ = 415 Hz) after Bressan, by Frederick Morgan, Daylesford, 1998

Instruments and Transposition

All Fantasias in the original key are played on voice flute (in d’). With one exception, the transposed Fantasias are played on alto recorders, assuming all labels “voice flute” in the list from the liner notes are correct (and with some guessing between the two alto recorders):

- #3: B minor, transposed to D minor — alto recorder in f’

- #4: B♭ major, transposed to E♭ major — alto recorder in f’ (or g’?)

- #7: D major, transposed to F major — alto recorder in f’

- #11: G major, transposed to C major — alto recorder in g’

- #12: G minor, transposed to A minor — voice flute in d’

Tempo, Repeats

How does this interpretation sound? With just two exceptions ( the Grave in #2, the first movement in #5), Dorothee Oberlinger prefers faster-than-average tempi (overall about the same as Barthold Kuijken); she plays all repeats, except for the Presto in #4, which is in ABA form anyway, so repeat would make that AABABA. Note that Dan Laurin plays just the first repeat, AABA — also his only exception.

Articulation, etc.

Oberlinger uses excellent phrasing and distinct agogics — but without Steger’s craze / extravaganza. Where she is really unique in this comparison is in the articulation. Dorothee Oberlinger is unmatched in her virtuosity and sheer speed of articulation on the recorder, and she likes these fast staccato passages! It’s simply excellent, and so lively: she can just “poke” notes, producing extremely short, yet very well-defined tones! That articulation goes along with a rich, vivid set of ornaments that she uses almost abundantly in repeats and sequential sections, up to short cadenza-like passages near the end of some movements.

In Oberlinger’s playing, legato or broad articulation often serves as a way to emphasize parts of a phrase or melody. Articulation also serves to “extend” the dynamic range, e.g., very short staccato notes give the impression of a pp. Also, she uses a very moderate vibrato (to a degree that doesn’t really affect the pitch) — and only selectively, to highlight individual notes in a phrase or melody, or to let long notes (in slow movements) blossom out.

Sound, Tone

A word on sound and tone. Oberlinger uses a set of very nice, full-sounding recorders, the recording / microphone placement is such that the distinct “roughness” of the recorder sound is clearly (& nicely) audible, along with all details of articulation — however, without an excess of fingering and breathing noises, as with Maurice Steger. That said, Dorothee Oberlinger is not a sound / intonation / tone fanatic (fetishist? no insult intended!) like Dan Laurin: expression is more important than tone, and Oberlinger often explores the full range of capabilities of her recorders. She knows exactly how far she can go (especially with very high and loud notes). Her intonation is clean, yet sometimes “affective” (and of course not obscured by an excess of vibrato).

Conclusion, Rating

Clearly, my favorite recording by far, highly recommended: to me, the focus here is on fantasy, articulation, ornamenting, and virtuosity. Especially if you think that 50 – 60 minutes of solo recorder music is a bit long, this is the recording for you!

Héloïse Gaillard, Recorder

The Artist

More by coincidence I ran into an appraisal for a recording of these Fantasias by Héloïse Gaillard. The recording was made in 2013. I have not purchased or listened to this recording in full. The remarks below are based on information from the CD cover, as well as from Amazon previews, so this is not a proper review. Yet, I thought it is still worth mentioning this recording here:

Héloïse Gaillard is a young, yet firmly established French artist, playing recorders as well as baroque oboe. She plays in various ensembles such as Le Concert Spirituel (oboe) under Hervé Niquet, Les Talens Lyriques (recorder) under Christophe Rousset, Le Concert d’Astrée (recorder and oboe) under Emmanuelle Haïm, as well as in Les Arts Florissants under William Christie.

General Approach

Gaillard’s approach differs from the other recordings on recorder in several basic aspects:

- The Fantasias are not arranged in the sequence of the score (see below).

- Only four Fantasias (#1, #6, #7, #8) are played in the original key and pitch, all others are transposed to a different key and/or played in a higher octave.

- She doesn’t just use tenor (c’) & alto recorders (f’ or g’) or a voice flute (d’), instead, she uses all of tenor (c’), alto (f’), soprano (c”) and sopranino (f”) recorders (all tuned relative to a’ = 415 Hz).

Instruments, by Fantasia

Here’s the list of the Fantasias in numeric order, the instruments used, and the keys chosen:

- #1: A major (tenor recorder in c’)

- #2: A minor, transposed to D minor (alto recorder in f’)

- #3: B minor, transposed to D minor (alto recorder in f’)

- #4: B♭ major, transposed to E♭ major (alto recorder in f’)

- #5: C major, transposed up by an octave (soprano recorder in c”)

- #6: D minor (tenor recorder in c’)

- #7: D major (tenor recorder in c’)

- #8: E minor (tenor recorder in c’)

- #9: E major, transposed to G major (alto recorder in f’)

- #10: F♯ minor, transposed to A minor (alto recorder in f’)

- #11: G major, transposed to B major (sopranino recorder in f”)

- #12: G minor, transposed up by an octave (soprano recorder in c”)

Recording Sequence

And here’s the list, in the order of Héloïse Gaillard’s recording:

- #7: D major (tenor recorder in c’)

- #3: D minor (alto recorder in f’)

- #12: G minor (soprano recorder in c”)

- #9: G major (alto recorder in f’)

- #8: E minor (tenor recorder in c’)

- #10: A minor (alto recorder in f’)

- #6: D minor (tenor recorder in c’)

- #2: D minor (alto recorder in f’)

- #1: A major (tenor recorder in c’)

- #5: C major (soprano recorder in c”)

- #4: E♭ major (alto recorder in f’)

- #11: B major (sopranino recorder in f”)

The reordering is maybe debatable, as is the fact that now there are three Fantasias in the same key (D minor), whereas Telemann did not re-use any key. But these are minor, probably irrelevant objections.

Comments from France

The reviewer (Pascal Gresset) from Radio Classique is very enthusiastic (excerpt only, translated): “After Frans Brüggen, many made attempts on recorder with sometimes very questionable bias … up to this version of Héloïse Gaillard, who has emerged as one the best of all.“ I don’t want to reproduce the entire review here — but the text closes with “At the same time a radically different version of the Fantasiss is appearing, by Dorothee Oberlinger (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi), but, although the comparison is interesting, it is not able to dethrone this one.“

My Comments, Based on Previews Only

I have listened through the Amazon previews, which (for a change) are quite informative and — I think — sufficiently representative, though I don’t want to judge the quality of the recording sound or of the recorders based on these 1-minute preview snippets; see above for the discographic information — at the time of this writing, Héloïse Gaillard’s recording was not yet available in all Amazon locations. Let me just add a couple short notes from my perspective:

- You will find sections with the sonority found in Dan Laurin’s recording (I’m referring to recordings with alto and tenor recorder, of course). You may also find sections with some of Maurice Steger’s phrasing extravaganza.

- The broader range of instruments is an interesting idea, and Fantasia #11 on a sopranino (f”) sounds like an excellent fit. Though, this is clearly not in the scope of the original composition: in the realm of the traverso, this would be the equivalent of playing #11 on a piccolo in c”.

- For my (and my wife’s) taste, there’s too much vibrato — too heavy, and too much everywhere. I think the vibrato should serve to highlight specific notes in a phrase or melody. Also, I prefer a “lighter” vibrato.

- The vibrato is at the fringe of affecting the intonation.

- The articulation in general is much softer than Oberlinger’s — to the point where some rapid ornaments appear “washed out”, slightly superficial;

- On the other hand, Héloïse Gaillard appears to use a wide range of articulations and ornaments, comparable (in number and variation) to those of Dorothee Oberlinger.

- Dorothee Oberlinger’s playing is more agile, more accurate / “sharper”, more virtuosic in fast passages, articulation and ornaments.

My Preliminary Judgement

Again: this is the result of listening through preview snippets and therefore cannot represent a proper review! However, from what I was able to hear, this indeed sounds like an interesting recording — but I still do prefer Dorothee Oberlinger’s interpretation.

François Leleux, Oboe

The Artist, Oboe

In 2005, François Leleux (*1971) recorded these Telemann Fantasias on an oboe — definitely not the original instrument designation.

Instrument: Baroque?

I downloaded this from iTunes, hence I don’t have the liner notes, and I don’t have details about the instrument used for this recording. The front picture suggests a baroque oboe, lacking pretty much all keys and mechanics: the central part rather looks like a baroque recorder. However, I haven’t seen any confirmation for this. All Fantasias are in the original key (for a list see above). The instrument is tuned to a’=440 rather than a’=415 as typical for baroque instruments (half a tone higher than the above recordings on traverso or recorder).

Leleux is known for his soft tone. However, from the tone alone one cannot assume a baroque or period instrument. Especially as Leleux’ playing on this CD is simply perfect. There is not a single issue with articulation and intonation in the entire recording, and over the entire tonal range used in these compositions.

No, Not Baroque!

One does not need to go back to baroque oboes to conclude that Leleux is playing a modern instrument. Even oboes played by the Vienna Philharmonics now (the “Vienna oboe”, definitely not baroque instruments) have a noticeably softer, darker tone than modern French instruments. They also tend to be less accurate in the intonation (changes in volume tend to cause changes in the pitch, which the artist may need to compensate). On top of that, baroque oboes lacked the octave key. This forces the artist to produce higher harmonics by overblowing, which limits the variation in volume and precludes seamless and smooth transitions such as those heard in this recording.

From all this I’m sure that the instrument on these CDs is a modern instrument. I also haven’t seen any record of Leleux playing period, i.e., baroque instruments. In that sense, the cover picture is actually deceptive, misleading.

Notes on Leleux’ Oboe Playing

As stated, the oboe is not the instrument these compositions were written for. Plus, this is a modern instrument, with all the added benefits, such as clear and easy articulation and intonation over the whole range, no intonation issues with dynamic variations (pp .. ff). As far as I can tell, Leleux also uses at least partial circular respiration (closing the pharynx, playing with the air reserve in the mouth while breathing through the nose, permitting to play “infinite” phrases). He often plays multiple phrases with a single breath, and when he breathes, one only hears him inhaling, rather than exhaling first, as with traditional oboe playing. He often can afford the luxury of playing over explicit breathing rests.

It all sounds absolutely effortless — though of course, François Leleux is (along with Heinz Holliger, presumably) the absolute master on this instrument.

Interpretation

How does Leleux’ interpretation sound like, and how does it compare to thew other recordings? Well, one gets the full benefit of a modern wind instrument. As indicated above, the prime benefits are

- The articulation is sharper than with the other instruments. Even the shortest notes are well-defined, there is no “smearing out” in rapid passages and ornaments.

- The intonation is flawless (within the tuning definition, see below).

- The dynamic range is superior to all of the other instruments. Leleux observes all dynamic annotations in the score.

- Leleux’ phrasing is excellent; he does not interrupt long phrases with extra breathing rests.

- Even top-of-the-range notes he can (and does) play without giving up any tonal quality (dynamics, tuning, articulation)

- The vibrato is very soft and subtle. It is primarily present on long notes (as one might do on baroque instruments)

- The biggest plus in this recording, though, is in sections with “hidden” (or not so hidden) polyphony. No other instrument (in this comparison) can play the jumps between two melody lines so clearly. Even where these sections are very fast, the lower voice / notes remain very well-defined. Leleux even manages to play independent (and clearly audible) phrasing on the lower voice, even though the notes are all separated by gaps. It’s almost as if the lower and upper voices were overlapping!

Tempo

Leleux mostly uses a moderate tempo — with the oboe he can afford that without having to use extra breathing rests; there are some (tempo) exceptions where Leleux is faster than the average: the Vivace in #1, the Presto in #6, and the A tempo giusto in #10, but also in the in the Largo in #8, where the faster tempo makes sense — at least on this instrument: I could not name a movement where I would prefer a substantially different tempo. Leleux’ agogics are inconspicuous — the focus is on the excellent articulation and phrasing.

Ornaments, Repeats

As Dan Laurin, François Leleux is moderate in the addition of extra ornaments: these are mostly limited to repeats, or to second, third, etc. instances in sequences. Also, Leleux is the only artist who plays all repeats in the score, without exception.

Downsides?

There are some downsides with this recording, too:

- the instrument is using equal temperament tuning — one loses the added color from the tuning of baroque instruments;

- the ornaments used by Leleux to me are typical and appropriate for the oboe; baroque instruments such as the transverse flute, and even more so the recorder, allow for a much larger variety in articulation (though maybe not over the entire tonal range);

- some trills are almost machine-like (too fast, too regular);

- some ornaments are repeated literally (e.g., in the middle part of the Presto in Fantasia #12). I’d prefer more variation: ornaments to me should sound almost improvised, with some rhythmic freedom;

- the tone is very nice, even superb for an oboe (see above) — but it is definitely nothing Telemann could ever have envisaged; the extremely balanced sound over the entire range also implies less variation & color, as is typical for baroque instruments.

A Specific Remark

There’s an interesting detail in the last line of the Vivace in #1, which my wife — who has played this Fantasia many times in the past — noticed instantly, from two rooms away:

The point in question here is the trill (+) on the third note: in modern notation (“tr.“), this must be played c#/d (half tone trill), even though the bar begins with d# an octave below. The subsequent d# of course does not apply in retrospect. For a full tone trill, the trill mark (+) would require a # above the “+”.

Everybody in this comparison does indeed play a c#/d trill — except Leleux, who plays a c#/d# (full tone) trill. One could argue that Telemann may have implied d#, but may have forgotten — or the notation with the # above the “+” may not have been in use (I don’t see a single example of a trill with # or b alteration on the secondary note in any of these Fantasias); one might even claim that the d#…d in that bar represents sort of a false relation (“Querstand” in German) — though with this exception everybody plays a c#/d trill, and my (as well as most others’) ear does not object at all.

Conclusion, Rating

Despite the limitations mentioned above, I still think this is an excellent recording, and I’m drawing a lot of listening pleasure from it — maybe even more than from Dan Laurin’s CD!

Kevin Thompson, Euphonium

Thompson recorded these Fantasias in 2005 — on a euphonium.

A Euphonium, Really?

With all due respect for the amazing abilities of this artist on a brass instrument: in the context of this comparison (and of historically correct performances), using a euphonium for baroque music for the transverse flute is close to a joke, or a curiosity. Even if one might like the idea (Thompson’s virtuosity on this rather heavy brass instrument is astounding), the result is simply not comparable. The euphonium is so extremely different in its “language” (articulation, tonal / acoustic properties) from baroque woodwind instruments.

Transposition

All Fantasias required a down-transposition by a minor third (1.5 tones) or a major third (two full tones) in order to suit the tonal range and the possibilities of a baritone brass instrument in B♭:

- #1: A major, transposed to F major

- #2: A minor, transposed to F minor

- #3: B minor, transposed to G minor

- #4: B♭ major, transposed to G♭ major

- #5: C major, transposed to A♭ major

- #6: D minor, transposed to B♭ minor

- #7: D major, transposed to B♭ major

- #8: E minor, transposed to C minor

- #9: E major, transposed to C major

- #10: F♯ minor, transposed to D minor

- #11: G major, transposed to E♭ major

- #12: G minor, transposed to E♭ minor

Non-Competitiveness

This transposition is the least of the issues — also some of the recordings on recorder are not in the original tonality, see above. Transposing music for a specific instrument was and is common practice. What really makes this recording non-competitive is that

Instrumental Limitations

- The artist is a true brass virtuoso. However, these pieces are difficult even on the instrument for which they are written, let alone on the euphonium. the latter is simply not flexible / fast enough for some of this music. Thompson sometimes slows down the tempo or chooses a slower pace altogether, with no obvious reason other than limitations of the instrument. The choice often is either to make a fast movement sound clumsy, or to slow down (a bit) for difficult passages, oddly breaking the flow.

- Some tonal jumps and melodic elements and ornaments are hard / difficult (impossible?) to perform on the euphonium. Thompson is using a specific, somewhat limited repertoire of ornaments that suits the possibilities of the instrument. This may only become obvious when comparing this recording with one on flute or other baroque woodwind instrument. However, it also is a restriction that makes the entire recording sound more uniform (along with the other limitations, see above and below), possibly even boring.

- The euphonium lacks dynamic range — it all sounds like mf up to f or ff, again making the recording sound much more uniform.

- Compared to baroque woodwind instruments, the Euphonium has very limited possibilities to differentiate the articulation, to vary the intonation, the tonal color. Overall, again, some of the variability is lost, in comparison to flutes or recorders.

Breathing Needs

- Compared to the traverso (or the Böhm flute) or a recorder (let alone an oboe), the euphonium requires much more air, causing extra breathing breaks, possibly in odd locations, breaking longer phrases.

- These breathing breaks are longer than on a woodwind instrument: it simply takes time to fetch the air for the next phrase, and to build up the pressure / tension for the subsequent notes. Especially when comparing this recording with any of the other CDs in this posting, the length of some breaks is actually irritating. Telemann simply did not think of the requirements for such an instrument.

- In this recording, some breathing breaks are in rather odd places, really breaking melodies, as well as breaking the musical flow.

A Damaged Track

- Last, but not least: I downloaded that recording via iTunes and found that track #9 (Fantasia No.9) has a defect at around 2’20” – 3’30”, i.e., in the second repeat of the first movement (Affettuoso), during the first bars in the second movement (Allegro). It’s clearly a defective CD. I called Apple’s support and asked for a repair of the track. The first answer was, that this is as it should be, this style being called “jagged and scratched” or something like that. I have forgotten the details, and I’m not a specialist in these music styles. My reply was somewhat steep (“You got to be joking…”). That caused them to re-rip the CD. Sadly, they took the same CD. They may have cleaned it or used an alternate drive: the bad section is slightly shorter, and originally there were two bad spots instead of just one now. Still, this did not really fix the issue. Perhaps the entire CD pressing / production is bad? In any case, this is the reason for the bad rating of Fantasia #9 in this recording.

Conclusion

You should only consider that recording if you are an absolute euphonium fanatic. Or if you are playing the euphonium yourself and maybe consider playing the Telemann Fantasias or baroque music for woodwinds in general. If you want track #9 to be intact, do not download from iTunes, but look for alternative sources. Unfortunately, I don’t see this as being available on Amazon (CD or MP3) right now. Except for second-hand offerings at outrageous prices.