Francesco Piemontesi, Charles Dutoit / Tonhalle Orchestra

Beethoven / Shostakovich

Tonhalle Maag, Zurich, 2017-10-18

2017-10-23 — Original posting

Dem Saalprovisorium auf den Zahn gefühlt: Francesco Piemontesi und Charles Dutoit in Zürich — Zusammenfassung

Ich erlebte Francesco Piemontesis Interpretation von Beethovens drittem Klavierkonzert in c-moll als betont impulsiv, vorwiegend legato, vorwärtsgerichtet und flüssig, mit Sicherheit und ausgezeichneter Technik, seine Linke gestaltete speziell im Staccato sehr differenziert. Insgesamt jedoch eine Aufführung, die den konventionellen Rahmen nicht sprengte.

Schostakowitschs Sinfonie Nr.15 (seine letzte) mit dem Tonhalle-Orchester unter Charles Dutoit kämpfte mit gelegentlichen Spannungsverlusten, Dem ausgezeichnet musizierenden Orchester kann man dies nicht anlasten, jedoch mag die Akustik dabei eine Rolle gespielt haben. Das Konzert war für mich zugleich die erste Begegnung mit der Tonhalle Maag, dem temporären Ersatz-Spielort, während die ehrwürdige alte Tonhalle und das Kongresshaus einer gründlichen Renovation und Restaurierung unterzogen wird.

Table of Contents

Introduction

My first concert visit at the temporary venue for the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, while the Kongresshaus Zurich, and with it the old Tonhalle is undergoing a thorough renovation for the coming three years. So, naturally, the hall and its acoustics (the atmosphere, etc.) absorbed major parts of my attention. From observing the people in the audience I suspected that most visitors experienced the hall for the first time.

The Venue

The temporary venue in Zurich’s West, called Tonhalle Maag by the Tonhalle Society, has been constructed inside an empty industrial hall (effectively a hall inside a hall), which to a large degree defined its proportions. The hall is slightly smaller than the venue under renovation, but wider, less high and shorter. The podium is fairly large, but fixed in size, and fairly flat, about 1 m above the parquet level (slightly ascending only in the rear-most part). As in the old hall, the parquet flat, there is a rear balcony, plus a balcony behind the podium. On the two sides, there are balconies with one row of seats only. The view from the balconies is excellent. The view from the parquet seating is good, though the view into the depth of the orchestra is very limited from the parquet.

Seating Comfort

The entire hall is built from bright spruce wood. One can smell the terpenes that are released from the structure. I quite like that smell, though after a while one ignores it completely. The seats are simple, individually screwed onto the floor, comfortable. They don’t have armrests, which tends to make better use of the available space (and people are less likely to fall asleep if there are no armrests!).

Acoustics

The most important aspect of the new venue are of course its acoustic properties. Press announcements, as well as reports from the first concerts were all fairly enthusiastic. For the most part, this concert confirmed these reports. I found the acoustics to be very clear, precise, transparent—analytical. One could hear all voices in the orchestra very well. On top of that, one could also accurately and instantly locate each instrument on the podium. On the other hand, I found the acoustics to be fairly dry, and devoid of any noticeable reverberation.

My seat was in row 7, directly facing the cellos, as the orchestra setup was the “modern” one (violin 1 — violin 2 — viola — cello). Despite this “unilateral” position, the cellos did not dominate—quite to the contrary. The violins sounded bright, clear, dominant, while the acoustic definition of the bass register in their entirety (cello, double bass) did not really convince me (individual solos were definitely OK). I wondered whether the “classic” (“antiphonal”) setup (violin 1 — cello — viola — violin 2) would have created a better impression on the cello / double bass section. I suspect that the musicians still need to evaluate the various option, in order to determine the optimum orchestra setup / arrangement for a given repertoire.

The acoustics were very clear and rich in detail, down into the faintest pianissimo (also with respect to noises from the audience!). At the other end of the scale, the orchestra very easily reached a very volume that was very impressive, maybe sometimes even oppressive. My neighbor occasionally felt compelled to protect her ears.

Piano Acoustics

The sound of a concert grand in this venue is an entirely separate issue, but equally of interest. From what I heard in this concert, with Francesco Piemontesi at the keyboard, I would claim that this venue is excellent for piano recitals, in terms of acoustic support and response. I did feel that the Steinway D-274 sounded somewhat dry. From this single concert I can’t tell whether that is due to the acoustics. It could also have been a matter of adjustment / intonation of the instrument.

The Artists

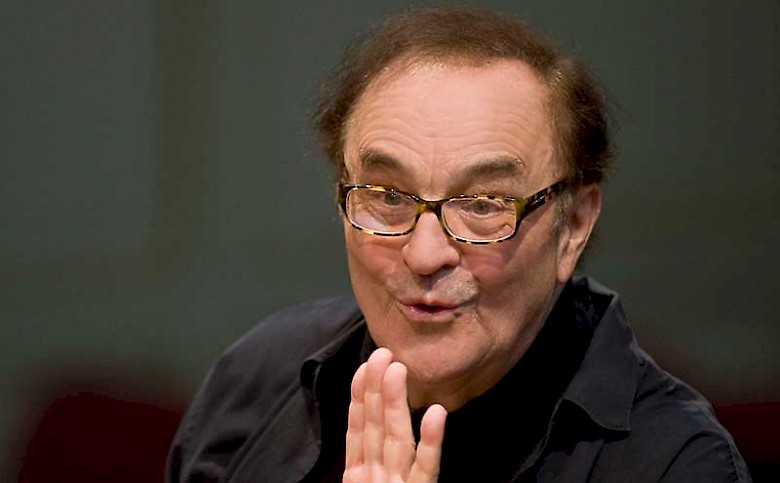

Charles Dutoit

The Swiss conductor Charles Dutoit (*1936) was born in Lausanne and received his education in conducting at the Conservatoire de musique de Genève. He is looking back to a long, successful, international career, with appearances all around the globe. Since 2007, he is chief conductor with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London.

Orchestra, Podium Setup

The concert opened with Beethoven’s third piano concerto. In the center of the podium there was a Steinway D concert grand. At least from my position, the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich appeared fairly large for a Beethoven concerto from around 1800. But this could just have been my impression, as the musicians obviously enjoyed the ample space and filled the podium in a rather expansive setup. From my position, the actual size of the orchestra was hard to estimate.

Sure, I would not call this a historically informed performance (the “most historically informed” part was the dry sound of the timpani). But, after all, the orchestra needed to be adequate for the modern concert grand, and a Steinway D per se cannot fulfill the requirements for historically informed performances. One should therefore not expect the impossible.

Francesco Piemontesi

The Swiss pianist Francesco Piemontesi (*1983) grew up in Locarno and received his education from artists such as Arie Vardi (*1937), Murray Perahia (*1947), and Alfred Brendel (*1931). He is pursuing a successful international career, both as soloist, as well as chamber musician. For more details on his vita see also Wikipedia. Despite his respectable career as concert pianist, for Francesco Piemontesi, this was only the second appearance in Zurich.

Concert & Review

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.3 in C minor, op.37

Trying to describe the Piano Concerto No.3 in C minor, op.37 by Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) would mean to bring sand to the beach. The concerto (Beethoven’s only concerto in a minor key) is all too well-known. For this review, let mew just list the movements:

- Allegro con brio (2/2)

- Largo (3/8)

- Rondo: Allegro (2/4) — Presto (6/8)

The Performance

I. Allegro con brio

In the orchestral introduction, Dutoit had the orchestra play with clear dynamics. He did not force anything, used a controlled, natural pace. He followed the score in the articulation. So far, the interpretation was inconspicuous. The entry of the soloist at bar 111 changed this. Francesco Piemontesi appeared to “make a statement” in the first six f bars: driving, impulsively pushing those upward scales. The impulsive, sometimes excessively driven playing remained characteristic throughout most of the fast movements. In the subsequent p segment, he switched to a more lyrical tone, though, but he remained fluent, rather legato.

Definitely, Francesco Piemontesi played with firm and flawless technique. In general, I liked his reflected agogics, the clarity of the playing. Piemontesi played in phrases and arches, rather than focusing on the fine details of articulation (let alone Klangrede), though he did articulate nicely with his left hand, particularly in staccato passages. In fast passages, I noted a certain tendency towards superficiality, especially with his frequent accelerating towards a climax. I really missed the occasional ritenuto ahead of peak / key notes in a phrase. On the other hand, I liked with the dolce part in Beethoven’s long cadenza. With the subsequent presto part, though, the artist appeared to succumb to the temptation of keyboard thundering on the modern concert grand.

II. Largo

The Largo started off with mellow articulation. Piemontesi exploited the full sonority of the Steinway D. This made many of the passages with hemidemisemiquaver and smaller notes (e.g., up to bar 37) sound slightly coarse, loud rather than singing. Just in the middle part, with its fee preluding in broken chord sequences, the artist softened the sound, blurred the articulation by using the sustain pedal, as requested by the composer. After this section, in bars 58ff., the piano was rather loud again. The modern grand made the 256th tremolo in the left hand (bar 63, with sustain pedal) sound blurred, almost dull. It was definitely far away from what it must have sounded like on Beethoven’s pianos.

III. Rondo: Allegro — Presto

The Rondo was the movement I liked most. It was flexible, playful, and light and clear in the left hand. The artists emphasized the gentle character of the intermezzo starting at bar 189 by taking back the tempo a bit. But then, in the staccato beginning at bar 257, where Beethoven writes “p, decrescendo, sempre pp“, Piemontesi starts rather coarse, mf, if not f. Only where the composer requests blurring using the sustain pedal, he reaches pp, along with the orchestral accompaniment. The solo in bar 320 starts very resolute, but then becomes playful, nicely follows the joking tone in Beethoven’s score. The final cadenza and the subsequent presto coda, was too fast, rather superficial, too much trimmed for “grand piano brilliance”.

Francesco Piemontesi definitely offered a rather conventional interpretation, overall. It was not revolutionary in any way. But it certainly wasn’t the intent of the artists to be provocative, or to attempt reconstructing what audiences at Beethoven’s time might have heard.

Encore — Mozart: Piano Sonata in F major, K.332 (300k), Adagio

For the encore, Francesco Piemontesi turned towards Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 – 1791). He selected the second movement, Adagio, from the Piano Sonata in F major, K.332 (300k). This was a good contrast to Beethoven’s virtuosic concerto. Also this was a conventional interpretation. I of course expected this, given the modern concert grand and the interpretation of the concerto. But the Adagio character was certainly well-matched: calm, not slow (this would be lento), nor did the movement ever feel like an Andante, despite the pacing Alberti figures in the left hand.

Shostakovich: Symphony No.15 in A major, op.141

After the intermission, the attention naturally turned towards Charles Dutoit and the Tonhalle Orchestra. Dutoit chose a single work, the last of Dmitri Shostakovich‘s (1906 – 1975) symphonies: Symphony No.15 in A major, op.141, which premiered in January 1972 in Moscow, under the direction of the composer’s son, Maxim Shostakovich (*1938). It’s a symphony in four movements:

- Allegretto

- Adagio — Largo — Adagio — Largo —

- Allegretto

- Adagio — Allegretto — Adagio — Allegretto

The symphony combines playful aspects, such as the quote from the overture to the Opera “Guillaume Tell“ by Gioacchino Rossini (1792 – 1868) in the first movement, plus additional, though less obvious / prominent quotes in the third and fourth movements.

The Performance

In this symphony, Shostakovich asks for 3 flutes, two oboes, clarinets, bassoons each, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, an extensive percussion section, celesta and strings. This certainly made good use of the available space on the orchestra podium.

I. Allegretto

In the first movement, what struck me right from the beginning was the fairly fast pace, which in my view did not fit the character of an Allegretto. It felt too much driven, pushed, close to being rushed in fast figures. Sure, the orchestra did not have a problem. It was in excellent shape, throughout. However, I missed the lightness, the humor, the playful aspect, also (especially, actually) in the Rossini quotes. There was an almost grim aspect to the interpretation. As listener, I would have enjoyed having a little more time to enjoy the details of the intricate, polyrhythmic segment.

I have mentioned the sound of the orchestra above. The violins sounded homogeneous, brilliant (and Andreas Janke‘s violin solo was excellent!), the brass section was equally impressive, as were the woodwinds (the solo flute in particular, in its prominent role) and all of the percussion group. The one minor quibble for me was that the bass section (10 cellos, 7 double basses) sounded a bit diffuse, badly defined, even though I was sitting close to the cellos.

It was also impressive to see / hear, how effortlessly the orchestra reached very respectable volume levels. Several times in the symphony, my neighbor protected her ears!

II. Adagio — Largo — Adagio — Largo

In the long second movement, I enjoyed the warm, clear chorale melody in the brass section. Equally excellent was the solo by the cellist Thomas Grossenbacher. The exception was maybe in his occasionally very prominent, somewhat heavy vibrato. Particularly the cello is very tricky in the intonation (e.g., when it goes up to the highest pitches, up in the “eternal snow”). This also applies to the trombones. No complaints here at all! Later in the movement, the chorale appears in the strings, and the music spontaneously reminded me of pieces by Henryk Mikolaj Górecki (1933 – 2010) or Arvo Pärt (*1935). In this case, of course, the association rather went from Shostakovich to these composers.

My primary quibble here is that over this long movement I felt a certain danger of the music losing tension. This continued in the last movement, but I’m not sure whether (in parts) the culprit was my limited familiarity with the music, or perhaps my personal, physical condition? We can’t always be in top “listening condition”. On the other hand, I expect from a good interpretation that it catches and keeps the listener’s attention, even if that listener is not “preconditioned” and/or thoroughly familiar with a composition. Maybe it is harder to focus the listener’s attention in the open acoustics of this venue?

III. Allegretto

The relatively short Allegretto works with strong contrasts, from pp to segments where a violin solo is alternating with outbursts of noisy passages. Interestingly, the outer parts use extreme crescendi in the string voices (with support / amplification by the flutes), similar to the ones found in the second movement (Serenade) of Shostakovich’s last string quartet (also No.15, see my recent review of a performance on 2017-10-01).

IV. Adagio — Allegretto — Adagio — Allegretto

A long, mostly dark movement, challenging in its length. Yet, while it is mostly sombre, if not death-laden, the movement features really beautiful cantilenas, such as in the violins, even playing with mutes and pp.

As already in the second movement, I felt some danger of the tension getting lost. I was pondering whether this was just me, or whether the spark did not ignite between orchestra and the audience, or perhaps even between conductor and orchestra? Maybe the open, clear acoustics made it harder for the musicians to “keep things together”? Maybe, the acoustics made it harder for a listener to immerse in Shostakovich’s music?

I can’t blame the orchestra for these reservations. Their playing was truly excellent throughout, both as an ensemble, as well as in all the solos. Except—just to repeat my quibble: in my opinion it wasn’t really necessary in this venue to be that expansive in the dynamics. At the upper end, less loud might have been more. But I suspect that over coming performances, both the orchestral setup, as well as the dynamics for this venue may see some adjustments / fine-tuning?

Conclusion

Overall: while the Tonhalle Maag may not offer the same quality of acoustics (especially in reverberation, supporting “envelope”, warmth and balance), it certainly is an excellent venue for bridging the renovation period. Moreover, it offers qualities, such as clarity (spatial and acoustic in general), detail down to the fines ppp, etc., that the “old” Tonhalle does not offer. And it offers a fresh, bright, very different atmosphere and visual appearance. I’m definitely looking forward to many interesting concerts over the coming three years!

Addendum

For the same concert, I have also written a (shorter) review in German for Bachtrack.com. This posting is not a translation of the Bachtrack review, the rights of which remain with Bachtrack.com. I created the German review using a subset of the notes taken during this concert. I wanted to enable my non-German speaking readers to read about my concert experience as well. Therefore, I have taken my original notes as a loose basis for this separate posting. I’m including additional material that is not present in the Bachtrack review.