Piano Works by Nikolai Myaskovsky & Nicolas Bacri

Sabine Weyer

Media Received for Reviewing

2020-05-28 — Original posting

“Mysteries”: Sabine Weyer spielt Klavierwerke von Nikolai Myaskovsky und Nicolas Bacri — Zusammenfassung

Auf ihrer neuesten CD präsentiert die luxemburgische Pianistin Sabine Weyer Klavierwerke von Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881 – 1950) und von Nicolas Bacri (*1961). In direkter Gegenüberstellung erklingen je die zweiten Sonaten der beiden Komponisten (Myaskovskys Sonate Nr.2 in fis-moll op.13, und Nicolas Bacris Sonate Nr.2 op.105), danach die jeweils dritte Sonate (Myaskovskys Sonate Nr.3 in c-moll op.19, gefolgt von Bacris Sonate Nr.3 op.122, “Sonata impetuosa“). Den Abschluss macht eine dritte Gegenüberstellung: Myaskovskys 6 Prichudi (Exzentrizitäten), op.25 (6 kurze Skizzen), gefolgt von Bacris Fantaisie op.134.

Direkte Bezüge sind innerhalb der Kompositionspaare kaum ersichtlich, bringen jedenfalls für nicht “vorbelastete” Hörer/innen keinen wesentlichen Zugewinn. Hingegen lohnt die Begegnung mit Myaskovskys Klavierwerk auf jeden Fall: dieser Komponist wird in der westlichen Welt viel zu wenig aufgeführt. Selbst die 6 Prichudi, vergleichbar mit Beethovens Bagatellen, sind eine Bereicherung!

Auch Nicolas Bacri ist außerhalb des französischen Sprachraums kaum bekannt. Mich beeindruckt vor allem seine ausgezeichnete zweite Sonate op.105, die durch die Verwendung des alten Dies irae Hymnus (aus der katholischen Requiem-Liturgie) direkt anspricht. Bacris Sonata impetuosa ist strukturell etwas einfacher, klingt jedoch für mich eine Spur “konstruiert”, “technisch”. Der vorwiegend ernste, wenn nicht gar düstere Ton erleichtert die Rezeption auch nicht—dagegen hilft selbst der finale G-dur Akkord nicht. Hingegen ist die abschließende Fantaisie op.134 zumindest oberflächlich eingängiger, trotz interner struktureller Vielfalt leichter fassbar.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Artist: Sabine Weyer

- The Composers

- What’s in the Recording?

- Listening Experience

- Myaskovsky: Piano Sonata No.2 in F♯ minor, op.13

- Structure

- The Music: The Introduction ( Lento, ma deciso )

- Allegro affanato — Poco meno allegro —

- Dies irae, dies illa — Allegro con moto e tenebroso

- Festivamente, ma in tempo — In tempo (Allegro) —

- Allegro affanato — Poco meno allegro —

- Allegro I e poco a poco più agitato — accelerando — accelerando molto — Allegro disperato

- Conclusion

- Bacri: Piano Sonata No.2, op.105

- Myaskovsky: Piano Sonata No.3 in C minor, op.19

- Structure

- The Music: Con desiderio, improvisato —

- Moderato con moto, stentato, ma sempre agitato — Tempo I, ma molto più pesante — Tempo precedente, ma più agitato —

- Molto meno mosso, con languidezza — Più affettuoso —

- Tempo iniziale — Molto desiderato, meno mosso e pesante — Moderato come primo, ma più agitato —

- Molto meno mosso, con languidezza — Più affettuoso — Tempo iniziale, ma più agitato —

- Tempo I — Stentato, poco agitando

- Conclusion

- Bacri: Piano Sonata No.3, op.122, “Sonata impetuosa”

- Myaskovsky: Excentricities — 6 Sketches, op.25

- Bacri: Fantaisie, op.134

- Myaskovsky: Piano Sonata No.2 in F♯ minor, op.13

- Sound, Instrument

- Performance

- Conclusions

- “Mysteries” — Media Information

Introduction

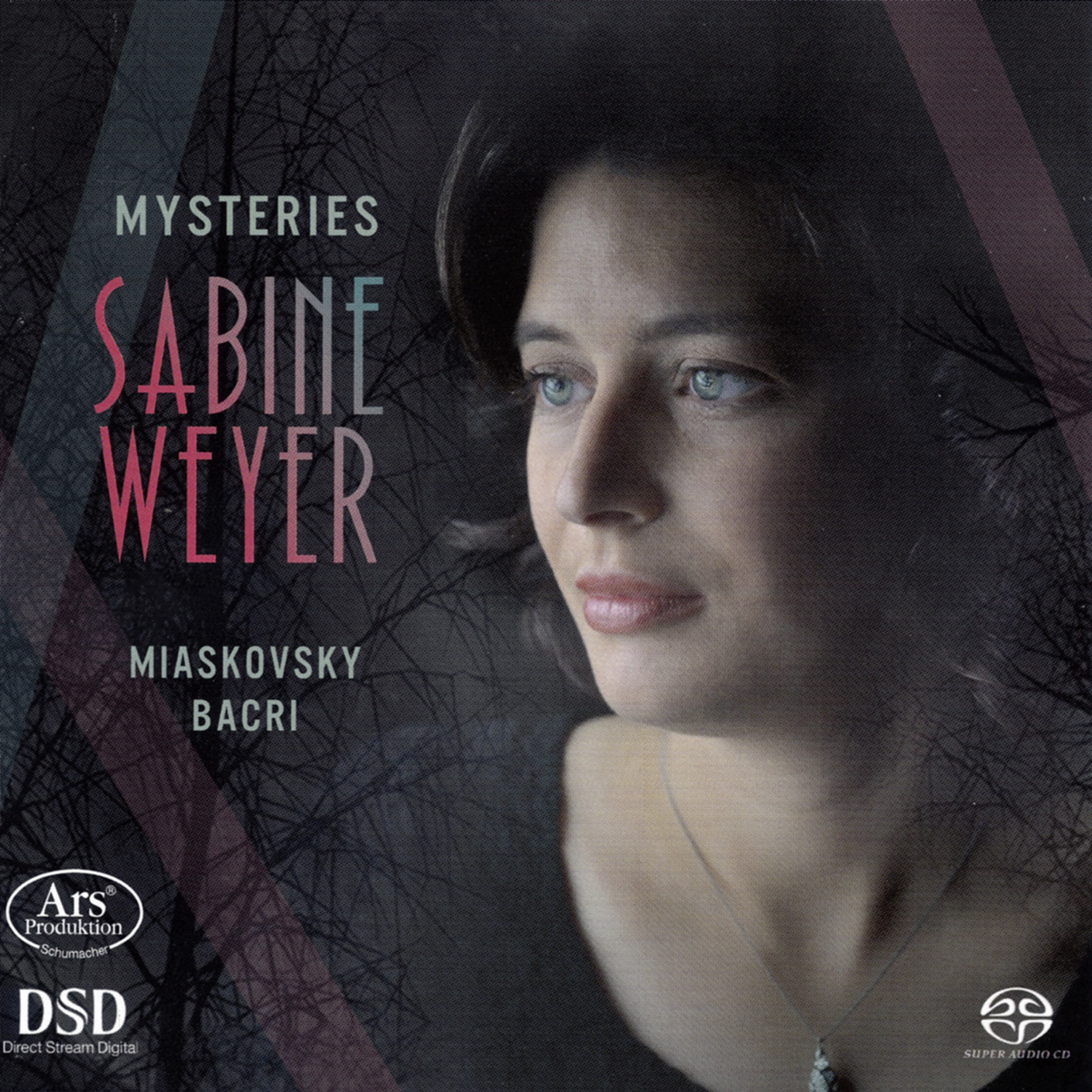

The above cover image is from a recording that I found interesting, for several reasons:

- Russian composers from the 19th and 20th centuries are very much in my field of interest. Especially if they are not (yet) part of the mainstream concert repertoire in my part of the world.

- I always had an interest in contemporary music. Concert visits in particular very much have revived that interest over the past years, since I started reviewing concert performances.

- I hadn’t heard of the artist so far. However, I received a suggestion to review the above recording. I listened to previews and encountered a good performance, technically and musically. On top of that, the recording confronts late-romantic Russian compositions with contemporary works. These again gathered my interest, not just in the confrontation, but also individually, on their own. So, here we go!

The Artist: Sabine Weyer

Sabine Weyer (*1988, see also Wikipedia) was born and grew up in the city of Luxembourg. There, she also started studying as pianist. She later continued at the Regional Conservatory in Metz, France, finally at the Koninklijk Conservatorium in Brussels, with Aleksandar Madžar (*1968). The artist ended her studies with a Masters Degree and a Postgraduate Diploma in piano performance. Over the course of her studies, she profited from encounters with teachers such as with Oxana Yablonskaya (*1938), and Michel Béroff (*1950).

The artist has since launched an international career as pianist. She is performing in illustrious venues and with major conductors and orchestras not just throughout Europe, but also in China. Sabine Weyer has engaged in chamber music recitals, with artists such as Aleksey Semenenko (*1988), Pavel Vernikov, Alena Baeva (*1985), Yury Revich (*1991), and Gary Hoffman.

Since 2015, Sabine Weyer teaches piano as professor at the Conservatoire de la Ville de Luxembourg.

“Mysteries” is Sabine Weyer’s fifth recording. It combines works by two composers, Myaskovsky and Bacri. Both these are close to the artist’s heart, see below. For her other published recordings see Sabine Weyer’s discography.

The Composers

Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881 – 1950)

The Russian composer Nikolai Yakovlevich Myaskovsky (also Miaskovsky or Miaskowsky, 1881 – 1950) was actually born near Warsaw, in Congress Poland. This was initially an independent territory (created when Poland was split up in the Congress of Vienna in 1815). It later lost its independence, becoming part of the Russian Empire. When Myaskovsky was in his teens, his family moved to Saint Petersburg. Myaskovsky initially learned piano and violin. However, he was discouraged from becoming a musician, entering a military career instead. While completing his training as engineer, he started composing, nevertheless. He took lessons with Reinhold Glière (1875 – 1956).

In 1906, he enrolled for the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. There, he became a student of Anatoly Lyadov (1855 – 1914) and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844 – 1908). Myaskovsky was the oldest student in his class. He soon got acquainted with the youngest student, Sergei Prokofiev (1891 – 1953). That turned into a lifelong friendship. Myaskovsky graduated in 1911. He then became teacher at the Conservatory. At the same time, he also worked as music critic. The two piano sonatas in this recording date from that period. Main influences on his music came from music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893) and—more importantly—Alexander Scriabin (1872 – 1915).

Middle and Late Years

Myaskovsky served in the first World War. He was wounded and also had to endure from multiple tragic incidents in his family. Still, he continued to serve in the Red Army till 1921. In that year, he was appointed teacher at the Moscow Conservatory and became a member of the Composers’ Union. The composer moved to Moscow, where he lived for most of the remainder of his life. In the 1920s and 1930s, he was considered the leading composer in the USSR. Myaskovsky tried his best not to enter a confrontation with the Stalinist regime. In 1947, that didn’t save him from accusations of formalism. The same happened to Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 – 1975), Aram Khachaturian (1903 – 1978), and Sergei Prokofiev.

For a more detailed biography please see Wikipedia.

Oeuvre

Myaskovsky produced a fairly large oeuvre, including 27 symphonies. It’s for good reason that he is sometimes referred to as the “Father of the Soviet Symphony”. There are also other choral and orchestral works. The latter include a violin concerto and a cello concerto. Also, Myaskovsky wrote chamber music (13 string quartets, a violin sonata, two cello sonatas) and songs. Plus, obviously, piano music, including nine published sonatas.

This is my second encounter with Myaskovsky’s music. In the context of a posting discussing works for cello and piano, I have briefly touched upon Myaskovsky’s Cello Sonata Nr.1 in D major, op.12.

Nicolas Bacri (*1961)

The French composer Nicolas Bacri (*1961, see also Wikipedia, better even Wikipedia.fr) was born in Paris. Some stages in his early career as composer:

- At age 7, he started taking piano lessons.

- 1975, he started taking lessons in musical analysis, harmony, and composition.

- 1979 – 1987: lessons in composition with Louis Saguer (1907 – 1991). In addition, lessons in conducting with Jean Catoire (1923 – 2005), a pupil of Olivier Messiaen (1908 – 1992).

- 1980 – 1983: studies at the Conservatoire national Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris. Nicolas Bacri’s teachers were Claude Ballif (1924 – 2004) for analysis, and Marius Constant (1925 – 2004) for orchestration. Plus, he of course continued studying composition, with Serge Nigg (1924 – 2008) and Michel Philippot (1925 – 1996).

Oeuvre

From 1982 on, Nicolas Bacri started receiving commissions for musical works. And in fact, he has been a highly prolific composer ever since. His Website (see Catalogue in the main menu) lists well over 450 works. These compositions are collected in currently 158 opus numbers (many of them covering multiple compositions). Apart from that, there is a series of unnumbered works, most of them easier, mostly or exclusively written for education, or for use in domestic performances.

The compositions range from orchestral / symphonic works (7 symphonies, concertos, etc.), vocal works (such as cantatas, motets, etc.), to a large body of chamber music works. And there is a limited range of piano music (including 3 piano sonatas), plus other solo works.

What’s in the Recording?

Sabine Weyer put together a set of works by Nikolai Myaskovsky and Nicolas Bacri. Each of these is represented by three compositions. The works are arranged in pairs, an alternating sequence. There are two piano sonatas by each of the composers, plus two smaller works: Myaskovsky’s Prichudi (6 short sketches, 2 – 3 minutes each), and a Fantaisie by Nicolas Bacri. All sonatas and Bacri’s fantaisie are in one single movement / track each:

- Myaskovsky: Piano Sonata No.2 in F♯ minor, op.13 (1912) — 14’29”

- Bacri: Piano Sonata No.2, op.105 (2007, revised 2008/2010) — 13’08”

- Myaskovsky: Piano Sonata No.3 in C minor, op.19 (1920, revised 1939) —14’54”

- Bacri: Piano Sonata No.3, op.122, “Sonata impetuosa” (2011) — 12’47”

- Myaskovsky: Excentricities (Причуды / Prichudi, Whimsies), 6 Sketches, op.25 (1917-18, revised 1923)

- Andante semplice e narrante (A minor) — 1’51”

- Allegro tenebroso e fantastico (B minor) — 1’58”

- Largo e pesante (B♭ minor) — 2’30”

- Quieto: Lento (A minor) — 2’05”

- Allegretto vivace (G minor) — 3’11”

- Molto sostenuto e languido (F♯ minor) — 2’29”

- Bacri: Fantaisie, op.134 (2014 / 2016) — 7’11”

Listening Experience

On purpose, I have not done a lot of research on the pieces. I also did not listen to or watch “competitive” performances. Rather, I wanted to offer a fresh, unbiased impression from these compositions. However, I did download the sheet music for Myaskovsky’s compositions from IMSLP. With this, I can comment on Myaskovsky’s music based on the musical score. In other words: I can try relating what I hear to what I see. With Bacri’s compositions, there is no such “notation bias”. I’m merely describing my auditive impression. And the pictures and emotions that the music evokes.

Myaskovsky: Piano Sonata No.2 in F♯ minor, op.13

Structure

There are many tempo instructions in a single movement (ignoring the countless explicit rubato annotations). There are no repeats, no formal structure (such as a sonata movement) other than a double bar after the introduction:

- Lento, ma deciso —

- Allegro affanato — Poco meno allegro —

- Allegro con moto e tenebroso — L’istesso tempo —

- Festivamente, ma in tempo — In tempo (Allegro) —

- Allegro affanato — Poco meno allegro —

- Allegro I e poco a poco più agitato — accelerando — accelerando molto — Allegro disperato

The Music: The Introduction (Lento, ma deciso)

The sonata starts with big, expressive gestures in late-romantic harmonies. Initially, these harmonies are bright (though pesante). However, they form falling sequences / cascades, which adds melancholic tone. Indeed, the music softens, retracts from f into p in the bass, definitely now introspective, if not retrospective. After 12 bars already, the music comes to a halt, and a gesture deep in the bass (pp, crescendo) brings tension, maybe expectation, though more of an open question than hope—

Allegro affanato — Poco meno allegro —

After another pause, the Allegro affanato (breathless) brings the first theme with a restless, almost permanent quaver triplet movement in the left hand, consisting of a chromatically falling sequence of fourths and thirds over a bar. In the aftermath, the intervals in this sequence relate to (anticipate) the central motif / theme in the sonata. However, for the time being, this is no more than a hint. The right hand contrasts with mostly ascending quaver motifs in post-romantic chords / harmonies (Scriabin?). Agitation, expression, culminating in towering ff chord sequences.

There is a lovely, almost serene intermezzo (Poco meno allegro) with almost joyful semiquaver chains, leading into a passage of lightly ascending, gentle demisemiquaver chains, bulminating and ending in a falling semiquaver cascade.

Dies irae, dies illa — Allegro con moto e tenebroso

A sudden sequence of rolling semiquaver sextuplets in the bass prepares for the second theme in the right hand: in full chords, the medieval melody / theme, “Dies irae, dies illa“ (“Day of wrath! O day of mourning!”). This part of the Roman-Catholic Requiem liturgy. That earnest theme retains its presence from the Allegro con moto e tenebroso throughout most of the sonata. It gets altered both rhythmically, as well as harmonically. Sometimes, it hides in bass figures, then again is very prominent, on top of complex polyphonic textures. Then again, it resides in playful preak notes, in a bright major key, on top of chords in downwards-arpeggiated semiquaver sequences (L’istesso tempo).

Festivamente, ma in tempo— In tempo (Allegro) —

Grandiose gestures with the theme now very prominent (marcato ed espressivo), leading to an almost violent eruption: In tempo (Allegro). This again retracts into exhaustion

Allegro affanato — Poco meno allegro —

The initial theme (Allegro affanato) returns, more violent and expressive than in the first instance. The music grows in complexity, while also brightening up. In the Poco meno allegro, it evolves into an extended, lyrical cadenza which contrasts the quaver triplet motif in the left hand with fast running figures in the descant. One can still hear glimpses of the Dies irae theme, though, which in the end returns with the full right-hand chords, just as it was initially presented.

Allegro I e poco a poco più agitato — accelerando — accelerando molto — Allegro disperato

The return to F♯ minor (an extended Coda of sorts) brings a new theme, staccato, in the form of a fugue, into which the Dies irae melody reappears. It is initially discreet and in fragments only, then, as the music builds up to a final, climactic effort (Allegro disperato). The Dies irae theme also ends the sonata forcefully (utter despair?), in earnest, determined mood.

Conclusion

An excellent composition, even a masterwork, indeed, fascinating! The more I listen to it, the more fascinating the music becomes, and the more I like it. To me, this is the Dies irae sonata.

★★★★½

Bacri: Piano Sonata No.2, op.105

Structure

Unlike the relatively complex structure in Myaskovsky’s second sonata, Bacri’s op.105 consists of four distinct, and clearly identifiable segments, following the scheme slow — fast — slow — fast. Almost as in baroque Sonate da chiesa.

A Gentle, but Abstract Beginning

Bacri’s second sonata begins in a forlorn mood, with a sequence of isolated, single tones. Dodecaphony, or just a reminiscence thereof? There are twelve notes, indeed, and it may well be a twelve-tone sequence. However, I don’t think it really matters for the listener. What does matter is the atmosphere—a lonely, gentle, calm and reflective voice in the void. A second voice joins in, as in a canon, disappears again, while the initial melody keeps flowing, like a cantus firmus, but with variations.

The atmosphere persists, while the second hand decently adds colors and substance with chords. Harmonically, the music sometimes reminds me of music by Béla Bartók (1881 – 1945). But then again, there are moments where baroque chord sequences seem to shine through. Or is it just that the degree of abstraction that made me think of “strict” fugues by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750)?

More Bartók?

After 3’10”, the contemplative mood ends. The following segment is dominated by staccato, and very motoric. To me, it strongly resembles piano music by Sergei Prokofiev, such as his “war sonatas“. At the same time, it retains a scent of dodecaphony, as it gets more complex and virtuosic. There is no tonality, but the enthralling rhythmic, motoric aspect prevails over all dissonances.

“Slow”

At 5’20” the music returns to the initial gentle, reflective mood. It is now slower, more melodic, more harmonious, far less “abstract”—very lyrical, serene, and more expressive. Beautiful!

“Finale / Fugue”

At 8’45”, the final segment begins, with motoric, percussive ostinato octaves. After some jazzy moments, a virtuosic fugue sets in, with a complex “twelve-tone-like” first subject. There are two intermittent, contrasting episodes, which are more homophonic. A short, contrapuntal segments leads into the final, impetuous, energetic bars with contrariwise movements in the two hands, into the extremes of the keyboard.

Conclusion

A brilliant, enthralling composition—at least as fascinating as Myaskovsky’s Sonata No.2!

★★★★½

Myaskovsky: Piano Sonata No.3 in C minor, op.19

Structure

Just like the Sonata No.2, this one consists of a single movement, with detailed tempo annotations:

- Con desiderio, improvisato —

- Moderato con moto, stentato, ma sempre agitato — Tempo I, ma molto più pesante — Tempo precedente, ma più agitato —

- Molto meno mosso, con languidezza — Più affettuoso —

- Tempo iniziale — Molto desiderato, meno mosso e pesante — Moderato come primo, ma più agitato —

- Molto meno mosso, con languidezza — Più affettuoso — Tempo iniziale, ma più agitato —

- Tempo I — Stentato, poco agitando

The Music: Con desiderio, improvisato —

The sonata opens with strong, erupting emotions. Two rapid, falling descents contrast with short, but emphatic, heavy chord sequences in the descant, somewhat desperate, rebelling. Also these chord sequences form a kind of Leitmotif—they are emblematic for the entire sonata. Con desiderio? Desire? Yes, but strong, dark, uncontrolled, maybe violent desires.

Moderato con moto, stentato, ma sempre agitato — Tempo I, ma molto più pesante — Tempo precedente, ma più agitato —

The following segment starts pp: desire again? It is dominated by quaver triplet and semiquaver movement which gradually turns more and more agitated, culminating in the reinforced return of the falling chord motif from the introduction. Strong rubato dominates, indicative of strong, maybe conflicting emotions. Interestingly, some of the chord motifs in the Tempo I, ma molto più pesante appear to allude to the “Dies irae” motif from the second Sonata. However, here, that motif is not monodic, but formed from typically dissonant chords. Highly expressive, emotional music, fluctuating between eruption, rebelling exclamations and resignation, ultimately retracting.

After an intense climax, that section ends in a short (2 bars) reflective (sad, questioning, maybe resigning) recitative (calando).

Molto meno mosso, con languidezza — Più affettuoso —

Formally now in G major / E minor, Myaskovsky avoids traditional modes: the third in chords is often omitted, as are classic cadences. The music appears to ponder in languidness, then (Più affettuoso) turns lyrical, almost serene in the descant, while the left hand retains a pondering mood. Gradually the emotions return in waves—outbreaks and phases of resignation, full of rubato: about every second bar has a rallentando, stringendo, or a tempo annotation.

Interestingly, a frequent three-tone motif (punctuated quaver, semiquaver, quaver, later softened to three quavers) strongly reminded me of the opening in the Arietta from the Piano Sonata No.32 in C minor, op.111 by Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827). Even though the atmosphere could barely differ more between these two compositions. Once that idea set foot in my thoughts, I felt that there may be an analogy between the opening movement in Beethoven’s op.111 and the Con desiderio segments in this one—not in motifs, but in attitude / emotionality.

That said: harmonically, in textures and pianistic demands, the entire sonata is of course far from Beethoven’s music. Rather, it is close to late- or post-romantic works of the early 20th century, such as piano compositions by Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943).

Tempo iniziale — Molto desiderato, meno mosso e pesante — Moderato come primo, ma più agitato —

The above segment ends in retraction, almost comes to a halt. But then the conflicting emotions return, now with growing turmoil in the bass. Hesitating, urging, hesitating, erupting, the music culminates in a highly expressive, intense climax (Molto desiderato).

Molto meno mosso, con languidezza — Più affettuoso — Tempo iniziale, ma più agitato —

As there are conflicting emotions at the scale of bars and phrases, the entire sonata is swaying between larger expressive, often agitated segments and phases of languidness, reflection, pondering. As in the first instance, the Più affettuoso gradually builds up intensity again. It culminates in firm, imperious pesante gestures.

Tempo I — Stentato, poco agitando

After a stringendo descent into the bass, the final build-up begins at Tempo I, leads into an insisting ff statement (pesantissimo), precipitates into con fuoco bars, a fff exclamation. That fff is the ultimate climax in the sonata. The last four bars end in an ascending crescendo to ffff chords. However, the Stendando (stunted) indicates that this “last effort” remains behind the previous culmination. At least, that seems what Sabine Weyer appears to read into this ending.

Conclusion

This sonata lacks the catchy, central theme of the earlier op.13. And it is more serious, earnest. There are segments in the single movement, but these merely mark the intersections between subsequent dynamic and emotional arches / build-ups. And the music is bracketed by the recurring ff exclamations, as well as the repeated escapes from languidness. Strong music, highly emotional and expressive, fluctuating between languidness and intensity, between pondering and exclamation. A masterpiece also this.

★★★★½

Bacri: Piano Sonata No.3, op.122, “Sonata impetuosa”

Myaskovsky’s Sonata No.3 made me think of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s piano music. Here now, there appears to be a direct link to the latter’s Sonata No.2 in B♭ minor, op.36. Rachmaninoff’s sonata begins with a catastrophic, crashing fall into the bass. The falling crash that opens Bacri’s sonata is not quite as violent, but the similarity is evident. Here, it leads into turmoil, stirring passages, in which the initial, crashing figure keeps recurring.

A Leitmotif

In fact, these falling lines (broken chords, sequences, phrases) appear throughout the entire sonata. Often, they are associated or alternating with grumbling, menacing, rolling bass figures. The first minutes of the sonata are dominated by this turmoil. Strenuous, often polyphonic, power-draining music. To me, it expresses despair, desolation, maybe constriction and anxiety, but also struggle and resistance.

Lyrical…

Around 3’50”, a more lyrical, but still rather dim segment sets in, with canon- or fugato-like structures—baroque, but merely in the textures. This gradually leads into a longer, reflecting passage that signals waiting, holding. At 5’50”, falling motifs return with growing intensity. They resolve into a calm, serene scene. Sabine Weyer maintains the tension, the expectation. A crescendo does not resolve into brightness, let alone transfiguration. Rather, the music returns to (almost) a stagnant void, with a monotonic third motif in the bass.

Turmoil again

Pain, maybe, loneliness, despair, open questions that remain open, when around 8’40” a complex theme appears to start a fugue. Though, after a short while, emotional turmoil returns, and with it the falling figures from the first part. Also the grumbling bass line returns. It now is the accompaniment to a polyphonic descant, with voices sometimes in imitation, sometimes in contrariwise motion, then again imitating the grumbling motion from the bass line. Bacri remains strictly atonal, but ends the turmoil—with an unexpected G major chord.

All dullness goes away when the voices appear to form a “strict baroque fugato”. Of course it’s no fugato, and it certainly is far from sounding baroque, being atonal. That latter aspect doesn’t last long: the ending features increasingly tonal chord cascades. And these lead into a final, brightly glowing G major chord.

Conclusion

Compared to his op.105, Bacri’s op.122 features a simpler structure (expressive — lyrical — expressive). It is maybe somewhat more “constructed”, feels more “technical ” in some parts. And in its darker more earnest tone, it speaks less directly to the listener’s heart. The G major ending can’t help here.

Nevertheless, it’s very interesting, highly artful piano music, at least in parts technically demanding.

★★★½

Myaskovsky: Excentricities — 6 Sketches, op.25

The composer originally wrote his 6 Prichudi, op.25 (total duration 14’04”) in 1917 – 1918, two years before his Third Piano Sonata. The op.25 is one of several sets of musical ideas that the composer collected between 1907 and 1919. Ideas which he didn’t use in larger works, he published in such collections. Sabine Weyer compares them to Beethoven’s sets of 7 Bagatelles op.33, the 11 Bagatelles op.119, and the 6 Bagatelles op.126. That comparison is indeed not far-fetched:

1. Andante semplice e narrante (A minor”)

A calm, peaceful and short children’s song in AA’BA-form. The middle part (poco meno mosso, più pesante) contrasts with a more dramatic, slightly obscured tone—the menacing part in a fairy tale? Simple, nice.

2. Allegro tenebroso e fantastico (B minor)

Percussive ostinato octaves in the left hand—the tenebroso (dark, gloomy) part. The fantastico aspect is in the descant: flashes of glittering, short motifs, with a somber middle part (In tempo, ma poco languente).

3. Largo e pesante (B♭ minor)

The first part (11 bars) is a solemn, somber chorale-like melody in the bass, in simple octaves. The subsequent part takes up motifs from that chorale (a falling four-note sequence, in particular), in complex, late-romantic harmonies. To me, these allude to some of Rachmaninoff’s slow Préludes. The ending is mysterious, ppp. The inspiration for the motto of the recording?

4. Quieto: Lento (A minor)

A simple piece—and music like a single, open question: a secret message, memories, a riddle? A bedside story for children?

5. Allegretto vivace (G minor)

Clearly the longest of the pieces. Fast, restless, playful, even joyful at times. It feels like the post-romantic version of a two-part invention (although of course far from those by Johann Sebastian Bach!). A constant line of semiquavers runs through the piece, at times wanders from the descant into the bass, and back again. The second voice is mostly in staccato quavers. If I were to look for the “hair in the soup” in the performance: there is a very short moment (at most 2 – 3 bars, barely noticeable) towards the end of the first part, around the climax, where the semiquaver figures appear to lose some momentum.

For the middle part, L’istesso tempo, the notation switches from G minor (2/4) to B minor (3/2). For the most part, there is a bass ostinato, from a descending 1-bar motif in crotchets, while the right hand adds short, slow sequences of stepping intervals / chords—serious, earnest. An accelerando leads back into running semiquaver figures. In the end, this further accelerates into a chain of explicit trills in semiquaver triplets. These ultimately are curling up and away. Jolly, fun, entertaining!

6. Molto sostenuto e languido (F♯ minor)

A pensive, reflecting piece ends the series—calm, sometimes almost sotto voce. Initially, there is a theme in a single voice—sounding as if it were by Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918) or Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937). An imitation in the bass follows. And soon, the texture evolves into a complex web of voices and harmonies, wandering around, aimless, enigmatic, without resolution, vanishing like an open question. Is that the real mystery that gave the recording its name?

Conclusion

It’s these Prichudi which reveal the reason for the title “Mysteries” of Sabine Weyer’s recording. They form a little kaleidoscope of musical ideas, some simple / easy, some more complex, enigmatic—interesting, for sure! I suspect that the enigmatic nature of some of the pieces lies in the fact that these are “ideas in search of a purpose”. In other words, they are really just sketches that later might have been used as part of (or as theme for) a bigger structure / composition.

★★★★

Bacri: Fantaisie, op.134

This is the most recent one of Nicolas Bacri’s compositions on this CD, from 2014—a short piece of 7 minutes.

A Fugue?

A single, unaccompanied descant voice presents the theme for the fantasia. It’s a serene, light, innocent, but slightly melancholic melody—essentially atonal. Actually, I would call this “constantly floating tonality”: it feels tonal, but still doesn’t let the listener, the ear settle on a key. It still is open-ended when a second voice joins in with the theme, while the first voice moves on with a “comes” / accompaniment, as in a baroque fugue.

Episode?

Once the second voice has played the theme, there is a brief intermezzo with calm, “breathing” chords (a second theme?). The initial theme returns in the descant, with a very simple accompaniment of alternating thirds. No fugato, this time: rather, Bacri returns to the chords, which grow in intensity. The chords pick up a motif from the main theme, which then returns, now with chordal accompaniment. It ascends, up and up, splits into playful figures.

At around 3’25”, a complex, polyphonic segment appears to introduce a new theme—a fugue in the style of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata, but in late-romantic harmonies? No, that idea is abandoned, a grumbling bass prepares for a new segment, retracting into pp, expectations and tension are rising…

Another Fugue?

At 4’20”, a fugato with a new, complex and ornamented theme sets in. However, Bacri appears to abandon that idea, as the second picks up a short fragment, an ornament, rather, from the accompanying voice, expands it. The music becomes virtuosic and more rhythmic, almost jazzy, lively. It finally coalesces into a trill, into which the original theme returns. It’s not a fugue just yet. Rather, an open ending with crescendo and fermata appears to prepare for a cadenza.

Here now (5’20”), the initial theme returns, now in more regular, “tamed”, strict form, all legato. It develops into a complex, 4-voice fugue. A fugato, rather, as at the peak of complexity, the music appears to reach exhaustion, suddenly retracts into pp. At around 6’30”, a final crescendo builds complexity, starting with a theme fragment in the bass, more and more voices join in, in canon-like fashion—and Bacri lets the piece end with an open sixth.

Conclusion

A multi-faceted piece, playing with ideas. There is little “classic” development, but glimpses into baroque and classic polyphonic textures in contemporary context. The one bracket across the movement is the initial theme—which the listener will barely remember. Still, it is catchy enough for the listener to recognize it even in small fragments throughout the piece. At a first glance, it sounds like an arbitrary sequence of styles / textures. However, each of the segments is artful and attractive in itself. Very interesting music, for sure!

★★★★

Sound, Instrument

Sabine Weyer performs on a Bösendorfer 280 Vienna Concert. This is the first and top-of-the-line of the manufacturer’s latest / newest series of concert grands. That series is a new design from scratch—the instruments offer excellent sonority, as I can tell from previous encounters. Here, I would characterize the sonority as clear in the bass and well-rounded and balanced, warm, never acute, let alone shrill or too bright. In some recordings, the sound engineers over-emphasize the bass sonority—luckily, this isn’t the case here. The soundscape remains clear, transparent, also in complex textures.

Performance

Sabine Weyer’s playing is technically superb and leaves little, if anything to wish for. I’m not the person to judge whether Myaskovsky’s music appears in a “proper, Russian-style interpretation”. However, to me, the artist’s view of that music feels compelling, convincing. Both composers are among her favorites. She performs them often in concert, and hence is very familiar with their styles. On top of that, Sabine Weyer’s touch, her control of the instrument is excellent in dynamics and sonority. She never strains the instrument in loud passages, her p / pp is perfectly controlled and subtle.

Conclusions

A highly recommended recording! If you are not familiar with Nicolas Bacri’s music, it’s well worth exploring. The same holds true with Myaskovsky’s piano music—I really enjoyed it!

“Mysteries” — Media Information

Myaskovsky: Piano Sonata No.2 in F♯ minor, op.13; Piano Sonata No.3 in C minor, op.19; Excentricities, op.25

Bacri: Piano Sonata No.2, op.105; Piano Sonata No.3, op.122, “Sonata impetuosa“; Fantaisie, op.134

Sabine Weyer, piano (Bösendorfer 280 Vienna Concert No.122)

ARS Produktion, ARS 38 313 (SACD / DSD, stereo); ℗ 2020

Booklet: 40 pp. de/en/fr

Acknowledgement

The SACD/DSD for this review was sent to me by Barbara Hoppe, NO-TE e.U.