Rubinstein playing Albéniz, Granados, de Falla

Media Review / Listening Diary 2014-06-29

2014-06-29 — Original posting (on Blogger)

2014-11-12 — Re-posting as is (WordPress)

2016-07-21 — Brushed up for better readability

2018-01-05 — For Albéniz, added Alicia de Larrocha’s recording

2022-01-03 — Added recording dates and locations

Table of Contents

- Rubinstein’s Recorded Spanish Solo Repertoire

- Rubinstein’s Early Contacts to Spain

- What did Rubinstein Select to record?

- Piano Music by Isaac Albéniz (1860 – 1909)

- Addendum: Looking for an Authoritative Spanish Recording?

- Piano Music by Enrique Granados (1867 – 1916)

- Piano Music by Manuel de Falla (1876 – 1946)

Rubinstein’s Recorded Spanish Solo Repertoire

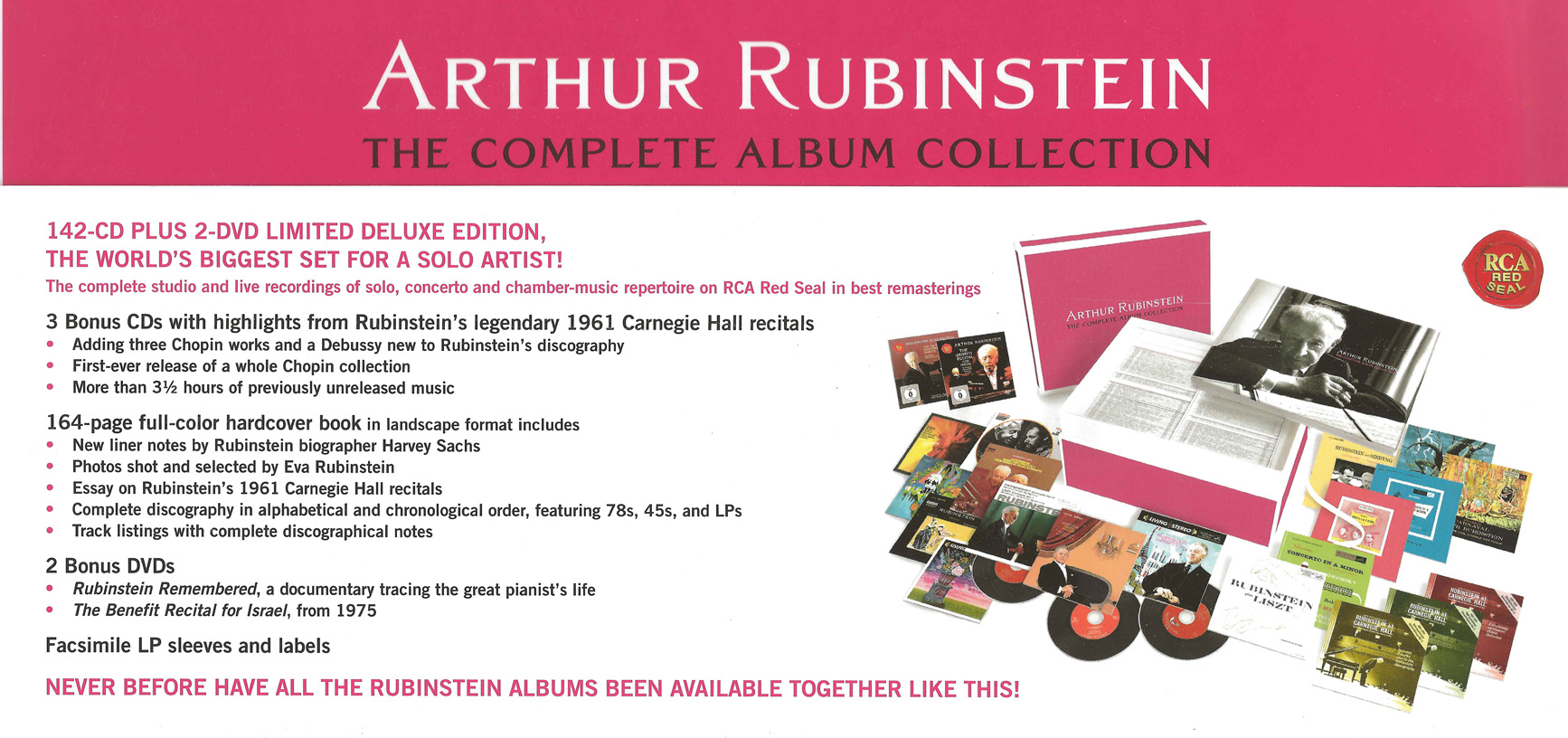

This posting is about solo compositions by Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados, and Manuel de Falla. This is an indispensable (albeit small) part of Arthur Rubinstein’s solo repertoire, included in the recently released “Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection“.

Rubinstein’s Early Contacts to Spain

Rubinstein must have picked up his Spanish repertoire in 1916. That year he essentially spent touring Spain, giving over 100 recitals. I don’t know what he covered in his solo repertoire back then. One should keep in mind that this was a period where he was essentially enjoying life and his early success. Later he confessed that he was not very careful in his playing. He was mostly focusing on the effect, letting many notes “fall through the cracks”.

Just one example that the artist later told with considerable amusement. Upon his arrival in Paris he was playing Chopin’s Etude in A minor op.10/11. He fascinated people by his playing, even though (his own words!) not a single note was correct in the Allegro con brio part.

Career, Repertoire

What he later (starting 1928) recorded (or selected from concert recordings) was fragmentary, spotty coverage of these Spanish composers at best. He picked the gems he liked, and probably also those for which he felt he could generate an adequate rendition. A rendition that satisfied his own, critical standards. That’s the standards that he applied after restarting his pianistic career with serious exercising and devotion to the music he was playing. Most of these pieces he liked to play as encores in his concerts.

The fact that Rubinstein’s Spanish repertoire included “just small pieces”, though, is not Rubinstein’s choice. The music of these composers is not following the classic or romantic models and forms (e.g., sonatas). It is essentially written in a “national style” and inspired by Spanish dances and folk music. This indeed led to collections or suites of short pieces. Also, for all but his very core repertoire (Chopin), Rubinstein was not encyclopedic. Even in his later years he always retained some hedonist trait.

One may consider the pieces of Spanish music for piano solo in Rubinstein’s repertoire fragmentary or incomplete. However, they still provide valuable insight into how Rubinstein’s interpretation evolved over his recording career.

What did Rubinstein Select to record?

One can assign the recordings to the following categories:

- Early recordings, dating back to 1929 – 1931, all made for 78 r.p.m. shellac discs. These obviously have limited audio quality. They are also from a period where pianists in general were not aiming for perfect performances. These recordings often sound somewhat blurred. It is hard to tell how much of this is due to technical limitations, and how much is due to slightly sloppy articulation, excess use of the sustain pedal, etc.

- Later recordings still made for 78 r.p.m. shellac discs (some were later released on LP), from 1941 – 1949. These definitely feature better recording technique, but also a more mature interpretation, clearer articulation, etc.

- Recordings that he made for 45 r.p.m. discs or LPs, 1953 – 1961. All recordings up to 1955 are mono. They were initially released on 45 r.p.m. discs. They demonstrate Rubinstein’s mature interpretation;

- There are a few previously unreleased recordings from 1949 – 1955. The documentation does not specify why these recordings were not released during Rubinstein’s lifetime. The artist states in interviews that he is very critical in recording sessions and would only agree with takes that satisfy his critical ear. But he also states that after a year or so his mind / interpretation has typically moved on. He could often no longer agree with recordings made a couple of months earlier. So, at times, the production process was too slow for a recording to pass Rubinstein’s scrutiny. Or, maybe he found that an interpretation was too close to an earlier one?

Spain in Concert Recordings

All of the above are studio recordings. However, in 1961 (at the age of 74), Rubinstein made a series of 10 recitals at Carnegie Hall, and he did allow for these to be recorded. It is a known fact that Rubinstein always “played for an audience”, be it only the recording team. Yet, in concerts, he probably let himself be guided by the spontaneous interaction with the public. However, of course, he still aimed to follow the composer’s (perceived) intent. Naturally, in a concert, there is no space for “post-production scrutiny”, other than denying the publication of a recording. So, this way, the concert recordings are “special”. They are often considerably different from Rubinstein’s studio recordings.

Spain in the Rubinstein Album Collection

One nice aspect of the “Complete Album Collection” (in particular also the Spanish repertoire) is that it has numerous pieces that are present several times, falling into several of the above categories. This makes it easy to follow Rubinstein’s artistic evolution. One can also see what difference it makes whether he was playing in concert vs. for a recording. Within the collection, the CDs below include works by the above Spanish composers. None of these composers (let alone these particular pieces) were represented in my music collection so far, hence this post is about Arthur Rubinstein’s interpretations alone.

The CDs

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CDs #1 – 5

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CDs #1 – 5: The Early Recordings 1928 – 1935

Arthur Rubinstein

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., track listing on CD sleeve

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CDs #11 – 14

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CDs #11 – 14: The Early Recordings 1938 – 1949

Arthur Rubinstein

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., track listing on CD sleeve

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CD #55

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CD #55: Falla: Nights in the Gardens of Spain; music of Granados, Albéniz, Falla, Mompou

Arthur Rubinstein

Enrique Jorda, San Francisco Symphony Orchestra

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp.; LP liner notes on back of CD sleeve

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CD #77

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CDs #77: Grieg: Piano concerto; Favorite Encores

Arthur Rubinstein

Alfred Wallenstein, RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., content listing on CD sleeve

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CD #131

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CD #131: Schumann: Symphonic Etudes op.13; Ravel: Forlane; Debussy: La plus que lente; Albéniz: Navarra

Arthur Rubinstein

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., LP liner notes on back of CD sleeve

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CDs #134/135

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CDs #134/135: Arthur Rubinstein — Unreleased Recordings

Music by Saint-Saëns, Debussy, Granados, Albéniz, Schumann, Anton Rubinstein, Mompou, Chopin, and Schubert

Arthur Rubinstein

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., track listing on CD sleeve

Arthur Rubinstein Collection, CD #140

Arthur Rubinstein — The Complete Album Collection

CD #140: New Highlights from Rubinstein at Carnegie Hall (10 historic recitals 1961)

Compositions by Debussy, Albéniz, de Falla, Granados, Liszt, Scriabin, and Stravinsky

Arthur Rubinstein

SONY Classical 88691936912 (142 CDs / 2 DVDs, mono / stereo); ℗ / © 2011

Documentation 162 pp., track listing on CD sleeve

Piano Music by Isaac Albéniz (1860 – 1909)

Albéniz could probably be called one of the initiators / forefathers of Spanish music in the first half of the 20th century. That’s music based on popular folk dances and melodies. Albéniz was one of the founders of Spain’s (local) classical period in music. Rubinstein carefully selected a few key works by that composer.

Suite española, op.47

The Suite española, op.47 is a collection of four pieces, composed 1886 (after Albéniz’ death, the suite was re-published with four additional pieces). Rubinstein just recorded No.3, “Sevilla“, twice:

- in an early recording from 1929 (1929-01-23, Small Queen’s Hall, Studio C & D, London, first CD set listed above), the duration is 3’24”. The focus is on the keeping the drive, the dance rhythm: an enthralling piece and interpretation, though in comparison to his later recording, this may sound somewhat superficial in the details;

- in the second recording from 1953 (1953-11-06, RCA Studios, Hollywood, CD #55 in the collection, published under the title “Nights in the Gardens of Spain“), the duration is 4’08”. The focus has moved towards detail, articulation, “telling a story”, moods. Inevitably, this version can’t feature the drive, maintain the flow the way the early recording does.

Chants d’Espagne, op.232

The Chants d’Espagne, op.232 is a collection of five pieces (published 1892) of which Rubinstein selected No.4, “Córdoba“. Again there are two recordings, on the same two CDs / CD sets:

- the first one from 1929 (1929-01-23, Small Queen’s Hall, Studio C & D, London) takes 4’19”, while

- the second one dates from 1953 (1953-10-22, RCA Studios, Hollywood) and has a substantially longer duration of 5’53”. This appears to be a slightly different version: the first two bass notes/chords in the slow introduction are missing in the earlier recording. But again, especially in the fast second part, the focus now is on articulation, clarity, and dynamic differentiation. A very nice piece of music, and an excellent interpretation, indeed!

Iberia

Evocación (from Book 1)

Albéniz’ most famous composition is “Iberia“, a suite of 12 piano compositions, composed 1905 – 1909, and organized in 4 books (“quadern”) of three pieces each. These are very virtuosic / demanding on the artist. Rubinstein selected just two excerpts for his recording repertoire. The very first piece, “Evocación“ (Allegretto espressivo), is present in three recordings (all mono, of course):

- the first recording was again made in 1929 (4’38”, 1929-01-23, Small Queen’s Hall, Studio C & D, London) in the first CD set listed above): an excellent recording (especially considering its age!) with a warm sound, amazingly well-balanced in this remastering

- the second recording (4’46”) was made 20 years later, in 1949 (1949-12-23, Studio #6, New York City), and was never officially released in Rubinstein’s lifetime (included on the CD set “Unreleased Recordings” listed above). Maybe it was considered too similar to the first recording? It does in fact not add that many new aspects overall, but does occasionally sound slightly hard in the first part;

- finally, a third recording (5’02”) was made in 1955 (1955-12-27, Webster Hall, New York City). Also this was never officially released and is now included with the CD set “Unreleased Recordings“. Apart from the obviously better sound quality and some added subtlety / dynamic and articulatory detail in the softer parts, that interpretation isn’t all that different from the first one from 1929.

Triana (from Book 2)

The second piece from “Iberia” that Rubinstein selected (as an encore, most likely) is No.6 (the third piece in the second book), “Triana“. This is named after the Romani quarter of Seville. It is also included with the CD set “Early Recordings 1928 – 1935”. In addition, there’s an encore in a live recording from Carnegie Hall in 1961:

- the early recording is from 1931 (1931-12-14, Abbey Road Studio 3, London) and has a duration of 4’00”. This is a rather complex, virtuosic piece that suffers from the lack of spatial resolution and a somewhat “tubular” sound;

- in the live recording from 1961 (4’11” without the applause, CD #131 with the black cover, shown above)) one should keep in mind that this is a “real” (and very effective!) encore. Rubinstein played this at the end of a long recital, possibly more focused on effect rather than subtlety and detail (though it is a somewhat boisterous, wild dance). But then, this is a stereo recording with much better sound than the early studio recording.

Navarra

Finally, there is “Navarra“, a rhythmically intricate, virtuosic piece. It was originally planned as part of “Iberia“, but remained unfinished, completed by Albéniz’ pupil Déodat de Séverac (1872 – 1921). Here, we have two early recordings, plus another one as actual encore in a live recording from Carnegie Hall:

- the first recording is from 1929 (4’35”, 1929-01-23, Small Queen’s Hall, Studio C & D, London, first CD set listed above). Rubinstein played with lots of rubato, maybe a bit too focused on the effect / spectacle, occasionally somewhat superficial in the articulation. However, this is also exceeding the limitations of the recording techniques of those days.

- the second recording is from 1941 (4’51”, 1941-06-17, RCA Studio 2, New York City, second CD set shown above) is substantially better in terms of clarity, articulation, agogics, and overall dramaturgy / phrasing / musical flow. An excellent interpretation, and in my opinion the best among these three.

- the live recording from 1961 (1961-12-10, Carnegie Hall, New York City) has a duration of 5’08” (without announcement and applause, last CD shown above) is once more not focused on artistic and technical perfection, but lives from the moment, the spontaneity, the atmosphere at the conclusion of a concert recital. The missed keys are not due to Rubinstein’s age, but due to the “encore effect”…

Addendum: Looking for an Authoritative Spanish Recording?

I don’t mean to diminish Rubinstein’s performances of Albéniz’ music. However, if you are looking for a “truly Spanish performance” of all of the above pieces by Isaac Albéniz, in their complete compositorial context, here’s my strong recommendation:

Alicia de Larrocha (1986):

Albéniz: Iberia, Navarra, Suite española

Alicia de Larrocha

Decca 478 0388 (2 CDs, stereo); ℗ 1987 / © 2008

Booklet: 20 pp. en/fr/de

Alicia de Larrocha (1923 – 2009), the “grand old lady of Spanish piano music” has recorded all of “Iberia“, all of the “Suite española“, as well as “Navarra“:

- Iberia (83’49”):

- Evocación: Allegretto espressivo — 6’04” (Rubinstein — 1929: 4’38”; 1949: 4’46”; 1955: 5’02”)

- El Puerto: Allegro commodo — 4’11”

- Fête-Dieu à Séville: Allegro gracioso — 9’01”

- Rondeña: Allegretto — 7’23”

- Almería: Allegretto moderato — 9’49”

- Triana: Allegretto con anima — 5’06” (Rubinstein — 1931: 4’00”; 1961: 4’27”)

- El Albaicín: Allegro assai, ma melancolico — 7’27”

- El Polo: Allegro melancolico — 7’02”

- Lavapiés: Allegretto bien rythmé mais sans presser — 7’05”

- Málaga: Allegro vivo — 5’19”

- Jerez: Andantino — 9’51”

- Eritaña: Allegretto grazioso — 5’36”

- Navarra — 6’00” (Rubinstein — 1929: 4’35″”; 1941: 4’51”; 1961: 5’30”)

- Suite española, op.47 (35’30”):

- Granada (Serenata) — 5’03”

- Cataluña (Corranda) — 2’36”

- Sevilla (Sevillanas) — 4’37” (Rubinstein — 1929: 3’24”; 1953: 4’08”)

- Cádiz (Canción) — 4’32”

- Asturias (Leyenda) — 5’58”

- Aragón (Fantasía) — 4’23”

- Cuba (Capricho) — 5’24”

- Castilla (Seguidillas) — 3’02”

From the timing, one can see that for all four pieces that Rubinstein recorded, Alicia de Larrocha prefers a slower tempo. None of de Larrocha’s performances appear aiming at displaying virtuosity—the latter is a mere basis for her performances. Instead, she plays with a distinct “Spanish rubato”: she lives these folk rhythms: a must-have reference recording, absolutely!

Piano Music by Enrique Granados (1867 – 1916)

Another key exponent of the “classical Spanish national music style” (with significant influence on Manuel de Falla and Pablo Casals) was Enrique Granados, born 7 years after Albéniz. He died at the same age as the latter, in 1916, drowning in a desperate attempt to rescue his wife after their ferry was torpedoed by the Germans.

“Danzas españolas“, op.37

A key composition in the “Spanish national style” were his “Danzas españolas“, op.37, a collection of 12 dances for the piano (4 volumes of three dances each).

Andaluza

Of these, Rubinstein selected a single one: No.5, Andaluza (from the second volume, just 3’35”), which he recorded in 1954 (1954-02-12, RCA Studios, Hollywood). It’s simply an excellent recording and performance. The outer parts with their rhythmic tension and play in the accompaniment, the passionate melody in the right hand, and that melancholic middle section (maggiore) with its melancholy: very nice, indeed!

“Goyescas“, op.11

The “Spanish national period” was the second one in Granados’ oeuvre, following an initial phase with romantic style music. The last phase in his short productive life is often called his “Goya” or “Goyescas” period, after the piano suite and the opera with that name. The piano suite “Goyescas“, op.11, subtitled Los majos enamorados (The Gallants in Love), and inspired by paintings by Francisco Goya (1746 – 1828). The seven pieces in this suite are highly ornamented and apparently very difficult to master. They are considered the crown of Granados’ oeuvre. He later composed an opera with the same name “Goyescas“, using melodies from the piano suite.

Quejas, ó la maja y el ruiseñor

Rubinstein selected (recorded) one single piece from this suite: No.4, Quejas, ó la maja y el ruiseñor (Complaint, or the Girl and the Nightingale). From this piece, we have four recordings in the collection:

- The first recording is from 1930 (4’50”, 1930-07-22, Small Queen’s Hall, Studio C, London) part of the first CD set listed above). It is a rather romantic interpretation, with plenty of rubato, expressive, with a virtuosic ending in trills and fast garland scales.

Maturing Interpretations

- The second recording dates from 1949 (5’01”, 1949-06-30, RCA Studios, Hollywood). It was never officially released and is now part of the CD set “Unreleased Recordings” shown above. Sure, the sound is much better, clearer, lacking the odd hiss, featuring a much better frequency and dynamic range. It is unclear why this was never published. Maybe Rubinstein felt that the interpretation was still too close to the first recording? Or maybe Rubinstein’s mind had moved on after the recording, and he may soon have felt that the piece requires a different interpretation?

- Indeed, just four years later, in 1953, Rubinstein recorded this piece again (CD #55 in the collection, 1953-10-22, RCA Studios, Hollywood, published under the title “Nights in the Gardens of Spain“). Now his playing was slower (duration 6’10”), more thoughtful and subtle, introverted / contemplative, with less rubato, more clarity; an excellent interpretation!

- Finally, there is a live and stereo recording from a concert at Carnegie Hall in 1961 (1961-12-04), where he played this piece as actual encore. That is more spontaneous and less reflected / reflective than the 1953 recording. Interestingly, at least tempo-wise he returned to (almost) the first two recordings (duration: 4’56” without the applause), though he retains the more contemplative approach from 1953.

The latter two recordings are certainly both equally valid, while the first two give interesting insights into Rubinstein’s interpretative evolution.

Piano Music by Manuel de Falla (1876 – 1946)

After Albéniz and Granados, Manuel de Falla was the third key Spanish composer in the first half of the 20th century: born 1876, 9 years after Granados / 16 years after Albéniz, he was their contemporary. He survived his fellow composers by 30 and 37 years, respectively. The bulk of his oeuvre only appeared after Albéniz and Granados. It is therefore not directly comparable (in style) to that of the other two composers. One key composition is “Noches en los Jardines de España” (“Nights in the Gardens of Spain”) for piano and orchestra, which Manuel de Falla composed between 1906 and 1909. Arthur Rubinstein recorded this four times in his career (I’ll discuss this in a later post). In his solo repertoire, Rubinstein was very selective about Manuel de Falla, recording just five short pieces that he used as encores in his concerts.

Cuatro piezas españolas

Three of these (present in one single recording each) were original compositions by de Falla:

- From the Cuatro piezas españolas (composed ca. 1906 – 09), the last piece, Andaluza, was recorded in 1949 (1949-06-30, RCA Studios, Hollywood), under “The Early Recordings 1938 – 1949”. It’s a virtuosic, rhythmically rich and accentuated piece. It is originating in Andalusian dance music, but definitely in a more modern musical language than Granados’ piece with the same name. Rubinstein offers a very good interpretation. It is very well remastered, given that it was still recorded for 78 r.p.m. shellac discs.

El Amor Brujo

In 1914, Manuel de Falla composed a “Gitanería” (Romani piece), which he named “El Amor Brujo“. Later, 1916, he transformed this into an orchestral version with three short songs for mezzo-soprano. In 1924, de Falla created a “ballet pantomímico” from this music, which by now is the most well-known version. Finally, around 1930, de Falla created a suite for piano “El Amor Brujo” (G.69), using four popular movements from the ballet: Pantomima — Danza del terror — Romance del pescador — Danza ritual del fuego. These pieces retain the popular, classicistic style of the original composition.

Danza del terror

The two danzas were among Rubinstein’s favorite encore compositions: the Danza del terror now exists in three recordings by this artist:

- an early recording from 1930 (2’13”, 1930-07-22, Small Queen’s Hall, Studio C, London, included with “The Early Recordings 1928 – 1935”)

- a recording from 1947 (2’10”, 1947-05-08, RCA Studios, Hollywood), under “The Early Recordings 1938 – 1949”), and

- a live recording from a concert at Carnegie Hall, 1961 (1’54” without the applause, 1961-12-04, on the last CD shown above).

Danza ritual del fuego

A brilliant, very virtuosic, short piece, very effective as an encore! For once, Rubinstein’s performance appears to gain tempo over the years. However, that impression is mainly from differences in the way in which Rubinstein plays the slow(er) introduction, which to me is most conclusive in the live recording. For the fast(er) / virtuosic part, though, the very first recording is just as brilliant and impressive! Also the fascinating Danza ritual del fuego is present in three recordings:

- an early recording from 1930 (3’20”, 1930-07-22, Small Queen’s Hall, Studio C, included with “The Early Recordings 1928 – 1935”)

- a recording from 1947 (3’24”, 1947-05-08, RCA Studios, Hollywood, under “The Early Recordings 1938 – 1949”), and

- a recording from 1961 (3’29”, 1961-03-23, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City, among his “Favorite Encores” bundled into the CD #77 with the Grieg piano concerto).

One can easily see why this piece is both popular as a composition, as well as very effective as an encore! The last interpretation may lack some of the drive, may be less enthralling than the first two recordings. But overall, I find this last version most convincing, offering the most detail, better phrasing, agogics and articulation—simply most conclusive, overall.

El sombrero de tres picos

In 1917, i.e., during the First World War, de Falla composed a pantomime ballet “El corregidor y la molinera” (The Magistrate and the Miller’s Wife), for small chamber orchestra. A rework of this composition was commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev. The result was the ballet “El sombrero de tres picos” (The Three-Cornered Hat). This premiered in 1919. Manuel de Falla also created a piano version, of which Arthur Rubinstein recorded the Fandango and the Farruca (Flamenco-type dances):

- Danza de la Molinera (Fandango, Dance of the Miller’s Wife), recorded live in 1961 (1961-12-04), from a concert at Carnegie Hall (3’00” without the applause, on the last CD shown above) and

- Danza del Molinero (Farruca, Dance of the Miller), recorded in 1954 (2’11”, 1954-02-12, RCA Studios, Hollywood, CD #55 in the collection, published under the title “Nights in the Gardens of Spain“).

Being Flamenco music, both these pieces use the sound language of the guitar — to a degree that makes one long for that “proper” instrument. Nevertheless, they are interesting and demanding pieces for the piano!

Fantasía Bética — Never Recorded

Interestingly, Rubinstein commissioned a composition by de Falla, the “Fantasía Bética“, which was completed in 1919 and dedicated to the artist. Rubinstein performed it in New York in 1920 and played it a few times, but then dropped it from his repertoire. He never recorded it, unfortunately.

Listening Diary Posts, Overview