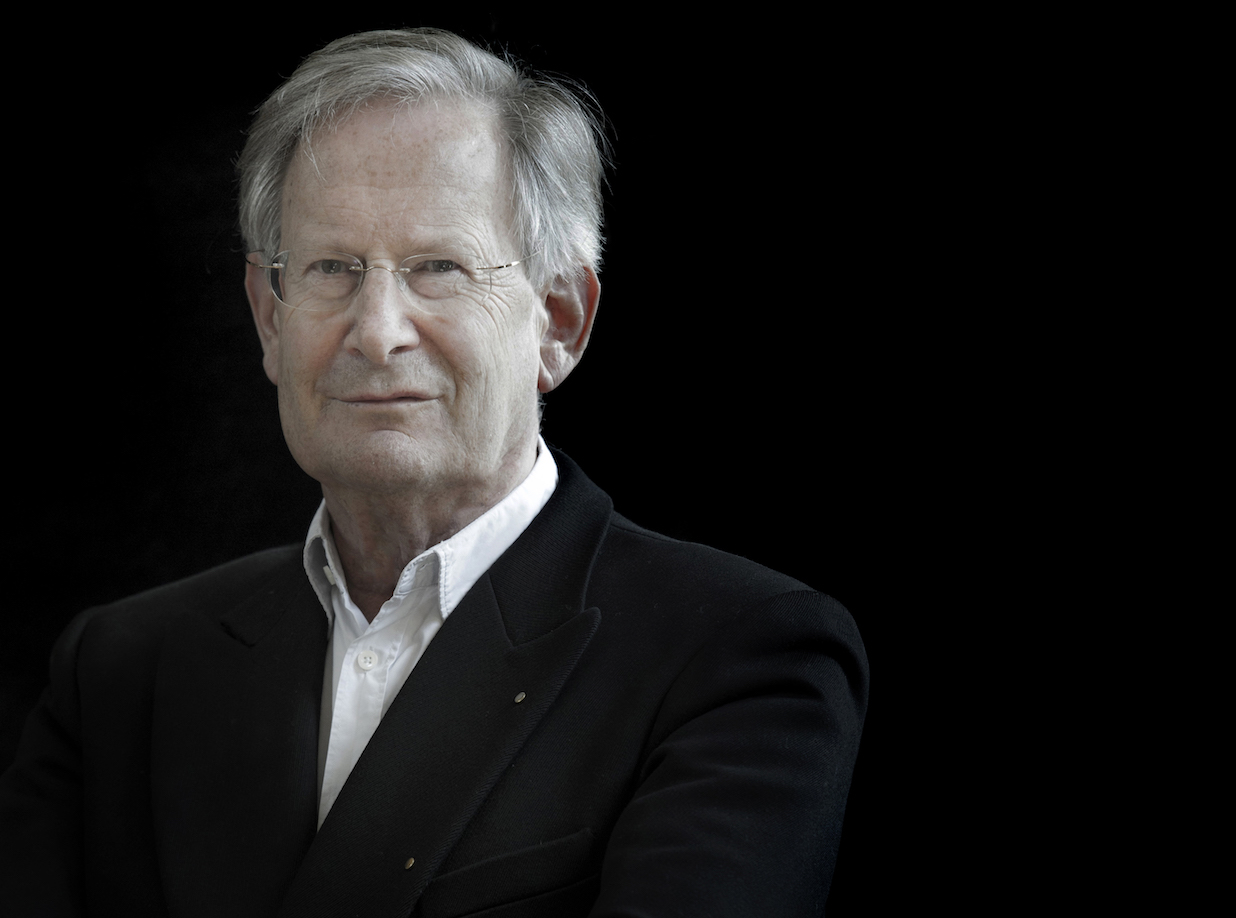

Sir John Eliot Gardiner / The English Baroque Soloists / Monteverdi Choir

Claudio Monteverdi: L’incoronazione di Poppea, SV 308

KKL Lucerne, 2017-08-26

2017-09-04 — Original posting

Oper, mit geschlossenen Augen zu genießen — Zusammenfassung

Eine halb-szenische Aufführung von Monteverdis “L’incoronazione di Poppea” im KKL Luzern, under der Leitung von Sir John Eliot Gardiner, der auch gemeinsam mit Elsa Rooke Regie führte. Als halbszenische Aufführung kam die Interpretation ohne Kulissen und (im Wesentlichen bis auf die Kostüme) ohne Requisiten aus.

Die Programmnotizen erwähnten den “Triumph des nackten Eros”, und in den sozialen Medien wurde gar auf “Sex and Crime” angespielt. Nun, Eros existierte in dieser Inszenierung allenfalls in Worten oder vielleicht in den Stilettos von Eros, hier von einer Frau (Silvia Frigato) gesungen. Letzteres war aus meiner Sicht nicht das einzige Manko dieser Aufführung: wer immer die bahnbrechenden Inszenierungen von Harnoncourt / Ponnelle in Zürich miterlebt hat, musste finden, dass hier etliche Chancen vertan wurden. Der Wegfall von Requisiten führte auch zu kleineren Diskrepanzen mit dem Libretto.

Sicher, die beiden Protagonisten (Hana Blažiková als Poppea und Kangmin Justin Kim als Nerone) sind ausgezeichnete Sänger. Sie wurden stimmlich überschattet von Marianna Pizzolato als Ottavia, mehr noch vom mächtigen Bass von Gianluca Buratto als Seneca. Die Begleitung (The English Baroque Soloists) fand ich gut, mit gewissen Abstrichen in der Ausführung des Continuo. Gardiner hat sicherlich eine historisch korrekte Aufführung angezielt. Wie weit das gelungen ist, kann angesichts der fragmentarischen Partitur kaum schlüssig beurteilt werden. Der schwächste Teil des Konzerts lag meines Erachtens in der Regie, und auch in inhärenten Limitierungen einer halbszenischen Aufführung.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The opera “L’incoronazione di Poppea“, SV 308, by Claudio Monteverdi (1567 – 1643) was the third and last concert in the Monteverdi cycle that Sir John Eliot Gardiner (*1943) was performing as part of this year’s Lucerne Festival in the White Hall of the Lucerne Culture and Congress Centre (KKL). Gardiner did not just perform the Monteverdi operas in Lucerne alone. He is currently touring Europe’s festivals and the U.S. (Aix-en-Provence, Bristol, Venice, Edinburgh, Lucerne, Berlin, Poland, Paris, Chicago, New York) with these operas.

For a general introduction about my background, why I attended this performance, and my reservations, etc., see my previous post about Monteverdi’s “L’Orfeo — favola in musica“, SV 318, performed in the same series, 4 days earlier.

The Cast

As already mentioned in my previous post about Monteverdi’s “L’Orfeo — favola in musica“, SV 318, the staff was essentially the same in all three operas (and all performances). At the core of the performances, there’s Gardiner’s orchestra, The English Baroque Soloists, which Gardiner founded in 1978, and which is now one of two orchestras in the “Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras” (along with the “Orchestra Révolutionnaire et Romantique” which specializes in the performance of music from the classical and early romantic periods). Of course, the choral parts are performed by the Monteverdi Choir, founded by Gardiner back in 1964.

Also here, I have written about the opera “L’incoronazione di Poppea” in that Zurich cycle in an earlier post discussing a DVD set with a video recording of these performances. In that post, I listed the singers and many of the instrumentalists involved. Back at the time of the original Zurich Monteverdi cycle (and still today), “Poppea” was my favorite among Monteverdi’s operas. I attended at least seven of Harnoncourt’s performances.

The Vocal Soloists

In this performance of “L’incoronazione di Poppea“, the following solo singers participated:

- Hana Blažiková, soprano (CZ, see also Wikipedia) — Fortuna, Poppea

- Kangmin Justin Kim, countertenor (KR) — Nerone

- Marianna Pizzolato, mezzo-soprano (IT) — Ottavia

- Gianluca Buratto, bass (IT) — Seneca

- Carlo Vistoli,countertenor (IT) — Ottone

- Anna Dennis, soprano (UK) — Virtù, Drusilla, Pallade

- Lucile Richardot, alto / mezzo (FR) — Arnalta, Venere

- Silvia Frigato,soprano (IT) — Amore, Valletto

- Furio Zanasi, baritone (IT) — Soldato I, Liberto

- Gareth Treseder, tenor (UK) — Familiare di Seneca

- Zachary Wilder, tenor (US) — Lucano

- Francesca Boncompagni, soprano (*1984, IT) — Damigella

- John Taylor Ward, bass-baritone (US) — Mercurio, Littore

- Michał Czerniawski, countertenor (PL) — Nutrice

- Robert Burt, tenor (UK) — Soldato II

Stage Direction, Costumes

Also here, the stage direction was in the hands of John Eliot Gardiner and of Elsa Rooke (born in Paris, to a father with Libyan roots). The costumes were designed by Gardiner’s wife Isabella Gardiner and by Patricia Hofstede (Atelier Paradis). The lighting design was by Rick Fisher.

The Setting

The general setting was essentially identical to that of “L’Orfeo“, with very minor changes. The harp was now in the right-side part of the orchestra, Gardiner was conducting (sitting) in front of the left-hand part. In this opera, the choir consisted of a few male voices. For the few choir scenes these singers stood at the rear edge of the podium, on a little, stair-like tribune. The solo singers moved from the rear to the front of the podium and back, either using the gap between the two orchestral groups, or (rarely) on the outer sides. Occasionally, they would interact with the orchestra. The two recorder players were now sitting in an acoustically more favorable position, at the left edge of the podium.

Lighting, Costumes

The text of the opera was projected in German and English onto a screen in front of the (closed) organ table. There was no audience on the podium gallery. That space was occasionally used for the performance as well.

There was no scenery, and with minor exceptions, no equipment was used (other than clothing), and lighting served to illuminate the location where the action happened, to “set the scene”. The white walls around the podium appeared in red, yellow, blue, etc. color lighting, again to set the stage for the action. The costumes were again simple and timeless, though more colorful than in “L’Orfeo“. The looks and to some degree also the character of a singer determine how the viewer perceives a role on stage. In a semi-stage production like this one, costumes are of lesser importance. However, they do indicate, highlight (and occasionally distort) the character in the opera. More on how the direction (and the costumes) depicted the roles in the text below.

The Composition

Of the operas that Claudio Monteverdi (1567 – 1643) has written, just three survived, aside from some fragments. While serving a position in Mantua, he composed “L’Orfeo — favola in musica”, SV 318, and at least one other opera “L’Arianna“. The latter has not survived the ages, except for one piece (Il lamento d’Arianna) that the composer published in his sixth book of madrigals.

From the last period of the composer’s productive life, two more operas survived: Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, SV 325, and the last one, L’incoronazione di Poppea, SV 308. The latter, based on a libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello (1598 – 1659) was first performed in Venice, 1643. After a short revival in Naples, 1651, the opera was forgotten about, until the score was rediscovered in 1888 only. More information is also available in my earlier post about a video recording of Monteverdi’s operas. Here, I’ll just briefly mention the action, as I walk through the performance.

Reading the Score

One should keep in mind that—unlike L’Orfeo—the score for Poppea is a mere skeleton, often just featuring the bass line (not even ciphered) and the vocal staves. Hence, the instrumentation etc. require extensive work, thorough research, and many decisions by the performer(s). Consequently, one will see vastly different performances of the same material. One example: the score specifies voices for specific vocal ranges. However, for alto and soprano roles it can often be assumed that these were performed by castrato singers. In turn, it also often happened that women (especially in comedy roles) sung tenor / male roles. This is not clearly stated in the score, though, hence up to the performer to decide.

There are no more castrati today (luckily!), Fortunately, countertenors are almost abundant these days, and they are able to sing alto and even soprano roles. One should remember, though, that the castration did not just prevent the breaking of the voice, but it also caused excessive growth of tubular bones, so castrati were typically not just tall, but also had big chests, and hence enormous breathing volume for long coloraturas, and the character of the voice was much different from that of a countertenor. All in all: today’s performances may use the presumably “original gender mix”. However, they still cannot claim to produce the truly original sound.

Dealing with Harnoncourt’s Legacy?

I may not be the only one on whom Harnoncourt’s pioneering Monteverdi cycle in Zurich had a lasting effect. Such legacy may well also affect performers. Also composers knew such problems. Examples are Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms, all of which felt an almost overwhelming burden from their forefather Beethoven.

I must assume that Sir John Eliot Gardiner knows about Harnoncourt’s Zurich performances. However, I don’t know to what detail he studied them (and whether he maybe even attended some of them?). It may just be my personal view, but I had the impression that Gardiner and Elsa Rooke absolutely wanted to avoid presenting what one might see as an imitation of (aspects of) Harnoncourt’s / Ponnelle’s production in Zurich. If that was indeed the idea (consciously or subconsciously), it (sadly) was prone to failure.

Sure, one cannot—and should not—forget or completely ignore pioneering performances (I certainly can’t, as a listener): in the Zurich Monteverdi cycle, the stage direction, the singing and the accompaniment were truly “magic matches”, virtually perfect in their own way. But I think that both imitating them or actively “playing against” them is a bad idea: the contrary of an exemplary performance will almost inevitably run into problems.

While of course keeping in mind the results of recent musicological research, it is better to try starting “from scratch”, and to develop a concept that serves the music and follows the composer’s intent, as perceived from his score. And one should ignore whether the result of such efforts in the end resembles that of predecessors.

The Performance

L’incoronazione di Poppea being substantially longer than L’Orfeo, there was an intermission in this performance. It was not placed at the intersection between two acts (the opera features a prologue and three acts, see below), but after scene 3 in act II. Within the two sections, there were no major interruptions, as already in L’Orfeo.

Characterization of the Roles in this Performance

The program notes featured an article with the title “The Triumph of Naked Eros“. In the social media, the Lucerne Festival even alluded to “Sex and Crime”. The way I read the libretto, there is certainly plenty of Eros in this opera. Crime—not so much, except that the main topic is how love (along with the craving for power) can corrupt anybody. And in this libretto nobody remains innocent, free of corruption, selfishness and guilt, or at least vanity (in the case of Seneca).

Sex wasn’t even alluded to, as far as I can tell. British understatement? Prudishness? Hard to believe in current times! And eros? Yes, there was a hint of erotic aura from the petite singer of Amore, Silvia Frigato (yes, a woman!), on her stilettos. But otherwise?

Crime: the closest to an actual (as opposed to intended) crime was Nerone ordering Seneca to commit die by suicide. His unilateral divorce from Ottavia is despicable (considering his motives), but hardly a crime that calls for severe punishment.

To be fair, I should state that it wasn’t one of the directors, or any of the musicians of this performance who wrote the program notes (and the postings in the social media).

Eros?

I think that eroticism is a firm part of the libretto: Poppea is a high class hooker, or at the very least a woman with a promiscuous lifestyle. A woman who uses eroticism to achieve her ambitious goals. Here, however, Poppea (Hana Blažiková) visually appeared as the presentation of innocence, rather than of seductive decadence. Lacking erotic flair may not be detrimental here (at least, one could certainly see her as a woman who wants to pretend being the pure innocence!). However, Nerone is the sheer prototype of a selfish, irascible man, craving for power. Here, the performance had a countertenor, Kangmin Justin Kim, singing that role. This per se is correct (and certainly makes sense in the final duet with Poppea). However, why did the direction give this singer such an androgynous appearance?

Further: with the women, short haircuts dominated (exception: Poppea). This may be fashion, or the direction’s preference, or mere coincidence through the selection of singers. The women did not wear wigs. However, that inevitably gave these singers a more masculine (or at least more gender-neutral), more dominant appearance. Drusilla (Anna Dennis) is a woman that competes with Poppea in trying to win (or buy) over Ottone (Carlo Vistoli), by means of her female attraction. Here, however, she appeared as the stronger personality than the man she is in love with. In the libretto, Ottone (Carlo Vistoli), is a weak, inconstant character (in line with his role being for countertenor), driven by his love (first for Poppea, then for Drusilla)—he appeared too strong and masculine.

Other Characters

Isn’t Arnalta, Poppea’s nurse, the prototype of a hilarious transvestite role? With a woman (Lucile Richardot) singing, most of the comic effect is forfeited already. The role of Nutrice, Ottavia’s nurse, is written for tenor (or a very deep female voice). Having a tenor (Michał Czerniawski) in this role is certainly OK. But why was he depicted as reminding of a sleazy, sordid clochard? This is meant to be the nurse to the (still current!) Empress Ottavia (Marianna Pizzolato)!

Overall, I had the impression that Gardiner (successfully) selected the singers for their voice only, or mainly. That is legitimate for a pure concert performance—which this wasn’t. But yes, the voices were very good, excellent even, pretty much throughout!

Prologo

Action: The Goddesses Virtù, Fortuna, and Amore in a debate about importance / relevance. Amore predicts that love will win the story that follows.

Being the first singer(s) in such a big opera is always difficult. Here, it helped that the two Goddesses Virtù and Fortuna were not performed by “minor artists”: Anna Dennis, who later also acted as Drusilla and as Pallade, was Virtù (here in brown-red), and Hana Blažiková, who even sang the main role, Poppea, was Fortuna (in a green dress). In contrast to my expectations, I had a slight preference for Anna Dennis’ voice here. However, Hana Blažiková may have saved her voice for later, or just deliberately understated a bit in this role. Silvia Frigato as Amore, in black and red, could not quite compete with the other two voice. But one should keep in mind that this role is likely for a boy’s voice. Consequently, the singer used a flat voice with very little vibrato. The duet Virtù – Fortuna was excellent, coherent.

The tempo was measured, initially with tendency towards legato and soft articulation (in line with my observations in L’Orfeo). After the introduction, the articulation freshened up a bit, but never turned anywhere near aggressive—a lyrical, serene atmosphere dominated.

Act I

Action: Ottone, former lover to Poppea, is in despair over Nerone being with Poppea. Nerone is fed up with his wife, Ottavia, whom he wants to expel. The latter seeks the help of Seneca, the philosopher, who wants to help her restoring proper order. Nerone ignores Seneca’s advice, consequently orders the philosopher to die by suicide. Ottone’s attempt to re-gain Poppea fails, and so he turns back to his former love Drusilla. This is a very long act—13 scenes, and well over an hour in duration.

Here, the orchestra—according to the program notes—featured three “horns”. These really were zinks, or cornetti—”horn” is a mis-translation of the latter term.

Ottone

The first, longer solo in this act is by Ottone, Carlo Vistoli: a countertenor with excellent voice / timbre, and with very good vocal presence. I found the dynamic span in the continuo a bit narrow (something I also found in L’Orfeo): Vistoli could rarely sing true p, let alone sotto voce. Was this a mis-perception about the capabilities of the acoustics in the KKL? While voice and singing were excellent, I found the character he depicted somewhat on the strong side, compared to how I see this role.

In the following scene, I quite liked the comedian roles of the two soldiers (Furio Zanasi and Robert Burt)!

Nerone & Poppea

The two protagonists, Nerone (Kangmin Justin Kim, countertenor, in blue) and Poppea (Hana Blažiková, soprano, now in all white) had excellent voices, well-fitting / matching (a pre-requisite for the final duet!). As already mentioned, however, I found Nerone too female (isn’t it sufficient for him to sing at a female pitch?). However, he definitely had excellent stage presence throughout the evening, and he is an excellent actor as well, credible, convincing—especially later, when he turns angry and furious at times. Also, his coloraturas were outstanding.

Sadly, I found Poppea’s acting too innocent, somewhat harmless, lacking erotic “flavor”. And (again, as in L’Orfeo), I found the continuo (the bass line, in particular) too monotonous. I don’t see the need for a cello, viola da gamba, double bass or organ to keep sounding (largely) throughout.

Arnalta

To me, it was a disappointment to see a female voice (Lucile Richardot) in this role. This not only defeated the comic nature of this role (no laughing in the audience!), but the singer also lacked strength in the lowest register. I can’t complain about Arnalta’s voice, though.

Ottavia

The (still) Empress Ottavia (Marianna Pizzolato)—a stately figure, and a very impressive and expressive, dramatic voice (stronger than the two protagonists!). She was one of the highlights of the evening! As an acting personality, she appeared stronger than Nerone—maybe not the ideal combination from the point-of-view of direction.

Nutrice

See above for my principal remarks on the role of the Nutrice (Michał Czerniawski). Besides the decadent looks, I also found that role to lack ambiguity and depth. It is definitely more than just comical (a secondary aspect in this role, I think).

Seneca, Valletto, Pallade

The other, true highlight of the evening was the philosopher Seneca (Gianluca Buratto): a big, very impressive bass voice, which really reminded me of Matti Salminen (*1945) in Harnoncourt’s Zurich performances (also a very strong role there!). Also, Silvia Frigato showed very good acting talent in the comic role of Valletto (her second role, besides Amore). Excellent: the announcement of Seneca’s looming death by Pallade (Anna Dennis) from the second balcony, high up, next to the organ.

Seneca, Nerone

The verbal duel between Seneca and Nerone is one of the prime examples of the stile concitato. This is Claudio Monteverdi’s “invention” (the prime example is found in the eighth book of Madrigals, in the well-known “Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda“). Sadly, Gardiner did not seem to really live out the acceleration, the dramatic build-up so typical for this style. He seemed hesitant to really engage in a dramatic accelerando. There is much more in this duel than what we heard here. Yet, Nerone was excellent and convincing in his furor, though he could maybe have been more ambiguous, more malicious.

Ottone, Drusilla

See above for general remarks. From the point-of-view of direction, the scene appeared to lack logic / justification: it was barely obvious why and how Ottone “switched” back his love from Poppea to Drusilla (his original love).

Act II

Action: Seneca, the philosopher, teaching his disciples, receives the order to die by suicide. Nerone celebrates the philosopher’s death (duet with Lucano). The Empress Ottavia seeks revenge and orders Ottone to kill Poppea, suggesting to do this disguised as a woman. Drusilla is willing to help and lends her clothes. He enters the imperial palace, where Arnalta gently sings Poppea into sleep. As Ottone wants to kill Poppea, Amore intervenes. Arnalta and Poppea call the guards, to seize the suspected murderer, Drusilla. I’m not commenting every scene in the text below.

Act II followed without interruption, attacca. Seneca learns about his upcoming death in two ways: first, while he enjoys solitude, through an announcement by Mercurio (John Taylor Ward, messenger of the Gods), from heaven (the gallery above the podium). Given Gianluca Buratto’s strong, dominant voice, the godly voice from above—though an excellent baritone—can hardly sound as authoritative as one might wish. However, the scene still left very little to wish for!

The second announcement is by Liberto (the tenor Furio Zanasi), Nerone’s messenger—another very short role. Too bad Seneca’s last note here is just right at the lower end of his voice, and hence barely audible! But Gianluca Buratto remains impressive nevertheless.

Famigliari di Seneca

This is followed by Seneca’s farewell from his disciples (Famigliari di Seneca). That’s a chance for Gardiner to present a small, all-male fraction of the Monteverdi Choir. As I see it, the choir “Non morir, Seneca” expresses utter pain and grief. It achieves this through chromatically ascending melody line, forming an impressive build-up in dissonances. Sadly, as already in “L’Orfeo“, I noted Gardiner’s tendency to soften dissonances. Rather than pointing out the anguishing pain by constant crescendo, Gardiner had the choir perform a diminuendo on every ascending half-tone pair. The most extreme dissonance at the climax was even softened by “harmonic filling” from the continuo accompaniment.

The second instance of “non morir, Seneca” is entirely a cappella, hence “purer”, and without harmonic softening. Actually, it was rather too clean: I’m not sure “instrumental perfection in singing” is needed in this moment of grief and farewell.

From the point-of-view of stage direction, Seneca’s suicide (indicated by partial undressing) wasn’t quite convincing. That’s a drawback of a semi-stage production, not to blame on the singer. The scene—and with it the first half of the concert—ended with an atmospheric, little, instrumental ritornello.

Intermission

It may sound odd to cut an act into two parts, in order to accommodate the intermission. However, a pause after Seneca’s death makes sense. In addition, the score appears to lack a scene at this point.

Damigella, Valletto

The following scene is a playful and harmless little love duet between Damigella (Francesca Boncompagni) and Valletto (Silvia Frigato). In the overall action, this duet makes little sense here: a weakness of the libretto? A weakness in the direction? Or a consequence of scene #4 missing in the score? On the other hand, in its last part (fulfillment in love), this duet appears to allude to / anticipate the final love duet at the end of the opera. With this, the second part in this concert appears in “closed, circular” form, and this way, the placement of the intermission, as well as the second half of the opera as such makes sense, logically, and musically.

It may just be my imagination, or the memory from the Zurich performances: I found it non-ideal (to say the least) to have Valletto as a trouser role. Interestingly, the first part of this duet (in this performance!) featured the most poignant dissonances in the entire evening. And these didn’t even stand for real pain, but rather for intense longing in love!

Nerone, Lucano

From the point-of-view of vocal technique (coloratura, messa di voce), the ecstatic duet with Nerone and his friend & companion Lucano (the tenor Zachary Wilder) is clearly the most demanding in the entire opera. For the latter, this is the only appearance—and a very short one. Unfortunately, the coloraturas weren’t quite convincing, nor even satisfactory.

Ottavia, Ottone

Scene 7 is missing in the score, and Gardiner omitted Scene 8 (Ottone alone). Time constraints?

When Ottavia forces Ottone to murder Poppea, the two involve in some more stile concitato—though less pronounced (in the score) that the first instance between Nerone and Seneca. From the point-of-view of acting & singing, the duet between Ottavia and Ottone is really excellent, convincing. Excellent coloraturas by Drusilla.

Nutrice (Drusilla, Valletto)

The comic aspects in the role of Nutrice only played in the subtitles…

Ottone, Drusilla

Here, Drusilla is meant to draw the picture of a youthfully careless and carefree woman doing anything to (re-)gain her love. In this performance, I would have preferred the singer to depict a younger, less mature character.

Poppea, Arnalta

Nice singing by Arnalta—not too convincing as a lullaby, though, nor is Poppea convincing when (supposedly) falling asleep. Also, in this scene, I found the continuo to be too loud & prominent, and the role of Arnalta could be more comical.

Poppea, Arnalta, Ottone, Amore

Excellent singing by Amore when she (!) intervenes Ottone’s attempt to strangle (!) Poppea. Arnalta’s raging outburst in stile concitato is only moderately comical.

Act III

Action: Under arrest, Drusilla declares herself guilty of murder, in order to protect her lover. Ottone intervenes, and both claim to be guilty. Nerone bans both from the empire. He now has a proper reason to expel Ottavia. Poppea enters the imperial palace, and Nerone crowns her Empress. The opera ends with the famous love duet between Nerone and Poppea.

This act was again following attacca. The advantage of a semi-stage production is that there are no delays and interruptions for changes in mise-en-scène.

Drusilla, Nerone, others

Both in terns of voice, as well as acting / psychology, Drusilla gave a very good performance. I already mentioned that the Littore (John Taylor Ward) refers to a knife or sword (col ferro ignudo), as written in the libretto. Excellent singing by Nerone, excellent acting in the furor (more stile concitato!), credible as actor, though as a figure, he is not.

Nerone, Poppea

Poppea appears as the stronger character then Nerone. This defeats the credibility of this scene.

Arnalta

In her (his) final scene, Arnalta makes serious attempts at appearing comical, but ultimately fails. The one noticeable smile in the audience is when the singer leans onto Sir John Eliot Gardiner, seeking consolation.

Ottavia

The last appearance of the former Empress, her farewell, is again simply excellent.

Poppea, Nerone—Coronation

The roles of the Tribuni e Consoli offers the male voices of the Monteverdi Choir another appearance with their impressive, powerful voices, in the coronation scene (well, there was no crown, just a laurel wreath). The roles of the Tribuni e Consoli are meant to be heavily ironic, possibly also comical—I did not see any of this here. The voices may have been gradually wearing out at this point—but here, Poppea’s voice appeared more robust than Nerone’s.

After this scene, there is a “heavenly trio”, later growing to a quartet, singing from the gallery above the podium. From the point-of-view of dramaturgy, this didn’t really make much sense (Harnoncourt didn’t have that scene—a late amendment or discovery?). A weakness of the libretto?

Poppea, Nerone

The direction had the two protagonists start their final duet “pur toi miro” from a distance, only approaching each other gradually. Trying to avoid falling into clichés? Eros? Possibly in the very last moment, when the two finally met…

But I can’t deny that even just this last scenes with Poppea and Nerone are tough on the direction / acting—even in a real stage production!

Concluding Remarks

A semi-stage production must be more tricky that a fully staged version: the “weight” of the production is entirely on the singers, the characters, their scarce actions and gestures. The music retains its central function, of course—but there is also no distraction from scenery or from actions. Yes, there are actions here, too—but in a stage production, the visual aspect plays a bigger role in general. Hence, in a production like this one, there is inherently more focus (and more scrutiny!) on the music and the singing.

The lack of accessories led to some questionable decisions on the part of the direction. For one, there was a logic discrepancy, in that Ottone (in disguise as Drusilla) tries to murder Poppea with a shawl. However, when Arnalta reports the incident to Nerone, she talks (sings) about a sword or a knife (following the text in the libretto). Then, a minor quibble: apart from clothes, the one and only accessory was a golden laurel wreath. Is / was that the right kind of emblem or crest for the “coronation” of the emperor’s / caesar’s spouse?

To summarize: the singing was excellent (particularly Seneca and Ottavia, as well as Nerone). The accompaniment was fine, with some reservations for the continuo. The weakest aspects of the performance in my opinion were with the direction, and (possibly inherent) with the limitations of a semi-stage production.

Addendum

For the same concert, I have also written a (shorter) review in German for Bachtrack.com. This posting is not a translation of the Bachtrack review, the rights of which remain with Bachtrack.com. I created the German review using a subset of the notes taken during this concert. I wanted to enable my non-German speaking readers to read about my concert experience as well. Therefore, I have taken my original notes as a loose basis for this separate posting. I’m including additional material that is not present in the Bachtrack review.