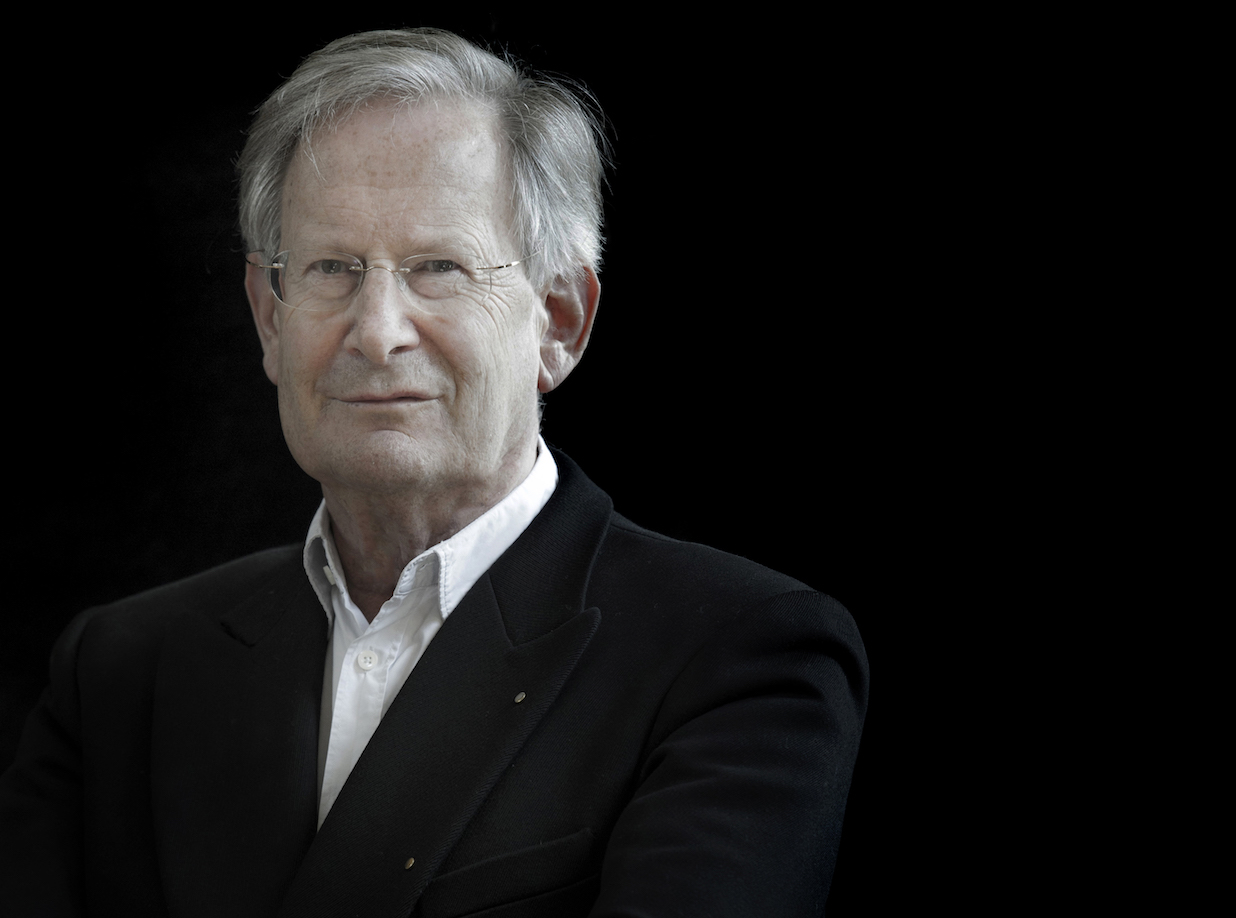

Sir John Eliot Gardiner / The English Baroque Soloists, Monteverdi Choir

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo — favola in musica, SV 318

KKL Lucerne, 2017-08-22

2017-08-31 — Original posting

Mehr Gardiner als Monteverdi? L’Orfeo am Lucerne Festival im KKL — Zusammenfassung

Sir John Eliot Gardiner brachte in Zusammenarbeit mit Elsa Rooke die drei Monteverdi-Opern in halbszenischen Aufführungen ins KKL in Luzern. Im Zentrum: das Orchester, The English Baroque Soloists. In diesem ersten Konzert also L’Orfeo.

In den wenigen Chornummern des Werkes gestaltete der Monteverdi Choir sich zu musikalischen Höhepunkten des Abends. Die Sänger bewiesen Agilität, Präzision, ausgezeichnete Diktion, produzierten vor allem einen bewundernswerten Chorklang, der den Saal problemlos füllte. Wie von diesem Dirigenten erwartet, folgte die Aufführung dem aktuellen Kenntnisstand bezüglich Spieltechniken, Ornamentation, etc., war gar exemplarisch in dieser Hinsicht. Die Solisten waren durchweg exzellent, Gianluca Buratto (Caronte / Plutone) gar spektakulär in Volumen und Stimmcharakter, Krystian Adam (Orfeo) eher im Ausdruck, im Sottovoce und in der Differenzierung.

Allerdings schien mir, dass für diesen großen Saal die Artikulation (eventuell auch die Größe des Ensembles) für mehr Klarheit und Transparent hätte angepasst werden müssen. Im Konzert erzeugte lediglich der Chor (bei Bedarf) ein echtes Forte. Ganz generell (mit Ausnahme der Chornummern) schien Gardiner eher auf Subtilität und Differenzierung in Bereich pp bis mf abzuzielen. Und auf “interne” Tragödie mehr denn auf das “große Drama”. Aus meiner Sicht war die Aufführung zu sehr auf Harmonie und Klangschönheit fokussiert (um dem Publikum zu gefallen??). Es war jedenfalls keineswegs eine radikale Interpretation.

Table of Contents

Introduction

I’m not making this a secret: I am biased—and biased I went into this concert! The point is that I’m still carrying with me the (to me) both legendary and revelatory (if not revolutionary) Zurich performances of the three operas that Claudio Monteverdi (1567 – 1643) wrote between 1607 and 1643. Monteverdi’s three operas (as well as hblais eighth book of Madrigals) were featured at Zurich Opera in the late ’70s. All under the direction of the late Jean-Pierre Ponnelle (1932 – 1988), a true genius in theater direction, and with by the late Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1929 – 2016) conducting the Zurich Monteverdi Ensemble (which later became the Orchestra La Scintilla Zurich).

I have written about the opera “L’Orfeo” in that Zurich cycle in an earlier post discussing a DVD set with a video recording of these performances. In that post, I listed the singers and many of the instrumentalists involved. I also mentioned that I visited all of these performances more than once. That experience made a strong and lasting impression on me. It’s an impression so strong that I resisted attending further performances of these operas. There was one exception to this, in 1979, when I attended a performance of Ulisse in London—and I was not impressed at all.

So, I wanted to avoid further disappointments. I even resisted attending Harnoncourt’s second (“post-Ponnelle”) Monteverdi cycle in Zurich. I felt that this could not possibly beat the earlier performances, even though Harnoncourt was correcting some of the musicological “errors” that he made in the first Zurich cycle.

Stepping Across Harnoncourt’s Shadow?

Now, I saw the opportunity to attend and review (parts of) the Monteverdi cycle that Sir John Eliot Gardiner (*1943) was performing as part of this year’s Lucerne Festival in the White Hall of the Lucerne Culture and Congress Centre (KKL). Why did I revert my decision? For one, this was going to be a semi-stage performance, hence restricted theater performance only (and Ponnelle’s direction had been one of the strongest points in the original Zurich cycle). So, I expected to be able to focus on the music. And I trusted Gardiner’s experience and knowledge in performing early baroque music.

Gardiner did not just perform the Monteverdi operas in Lucerne alone. He is currently touring Europe’s festivals and the U.S. (Aix-en-Provence, Bristol, Venice, Edinburgh, Lucerne, Berlin, Poland, Paris, Chicago, New York) with these operas.

The Cast

The staff was essentially the same in all three operas (and all performances). At the core of the performances, there’s Gardiner’s orchestra, The English Baroque Soloists, which Gardiner founded in 1978, and which is now one of two orchestras in the “Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras” (along with the “Orchestra Révolutionnaire et Romantique” which specializes in the performance of music from the classical and early romantic periods). Of course, the choral parts are performed by the Monteverdi Choir founded by Gardiner back in 1964.

The Vocal Soloists

For “L’Orfeo“, there were numerous solo singers, some with multiple roles:

- Krystian Adam, tenor (PL) — Orfeo

- Hana Blažiková, soprano (CZ, see also Wikipedia) — La Musica (Prologue), Euridice

- Lucile Richardot, alto / mezzo (FR) — Messaggiera

- Francesca Boncompagni, soprano (*1984, IT) — Proserpina

- Gianluca Buratto, bass (IT) — Caronte, Plutone

- Kangmin Justin Kim, countertenor (KR) — Speranza

- Furio Zanasi, baritone (IT) — Apollo

- Francisco Fernández-Rueda, tenor (ES) — Pastore I

- Gareth Treseder, tenor (UK) — Pastore II / Spirito I / Eco

- John Taylor Ward, bass-bartitone (US) — Pastore IV / Spirito III

- Michał Czerniawski, countertenor (PL) — Pastore III

- Zachary Wilder, tenor (US) — Spirito II

- Anna Dennis, soprano (UK) — Ninfa

The combination of Caronte and Plutone on one singer would not be possible in a real stage production. the biggest role by far is that of Orfeo.

Stage Direction

The stage direction was in the hands of John Eliot Gardiner and of Elsa Rooke (born in Paris, to a father with Libyan roots). The costumes were designed by Gardiner’s wife Isabella Gardiner and by Patricia Hofstede (Atelier Paradis). The lighting was designed by Rick Fisher.

The Setting

Clearly, the White Hall in the KKL was not designed for opera—hence the semi-stage production. John Eliot Gardiner arranged the orchestra in two separate parts, see the photo below. The segment on the left side of the stage included the violins (3 + 3), the violas (4), harp, two theorbos, baroque guitar, viola da gamba, a small chest organ (for the regal), and a harpsichord. The right-hand side featured the bass and wind segment, with two more theorbos, harpsichord, and a positiv organ.

At least from the rear of the parquet seating, there was no obvious association between the two orchestral segments, or the two continuo groups, and specific figures in the opera. Except that for most parts, the organ was used in the continuo, while the regal (left) was used specifically as accompaniment for Caronte and Plutone, i.e., the Underworld.

The choir usually stood at the rear edge of the podium, on a little, stair-like tribune. Choristers and solo singers moved from the rear to the front of the podium and back, either using the gap between the two orchestral groups, or on the outer sides. Occasionally, they would interact with the orchestra. Sir John Eliot Gardiner was conducting from a chair on the right-hand side segment of the orchestra.

Lighting, Costumes

The text of the opera was projected in German and English onto a screen in front of the (closed) organ table. There was no audience on the podium gallery. That space was occasionally used for the performance as well.

There was no coulisse, and with minor exceptions, no equipment was used (other than clothing), and lighting served to illuminate the location where the action happened, to “set the scene”. The white walls around the podium appeared in red, yellow, blue, etc. color lighting, again to set the stage for the action.

The costumes were kept simple and timeless, from white through beige tones to black (with one exception, see below).

The Composition

A lot has been written already about Monteverdi’s opera “L’Orfeo — favola in musica”, SV 318—I don’t need to present the piece here. Monteverdi wrote it in 1607 for a performance at the court of Mantua, based on a libretto by Alessandro Striggio the Younger (c.1573 – 1630). More information is also available in my earlier post about a video recording of Monteverdi’s operas. Here, I’ll just briefly mention the action, as I walk through the performance.

The Performance

There was no intermission in this concert. Gardiner performed the prologue and the five acts of the opera without interruption, quasi attacca, with the exception of a short tuning break after Act II.

Toccata

The music started even prior to the concert, when the Gonzaga fanfare (Toccata) sounded in the foyer, in order to lure the audience into the hall. That fanfare then sounded again, this time from the gallery above the podium: five trombones and three zinks. The program notes unluckily translated these with Horn—probably because in the Anglo-Saxon world, the instrument is also known as cornett or cornetto. The Zink uses a horn-type cup mouthpiece, but otherwise doesn’t resemble the brass instrument “horn” at all: it is actually made from wood, typically covered in leather, and it features finger holes. Later in the opera, the gallery served as a platform for the “heavenly sphere” in the action.

Prologue

The actual prologue features a single figure, La Musica (Hana Blažiková, who later also sings the role of Euridice). She introduces the audience to the tale of the opera, in five verses, surrounded and separated by a ritornello. The prologue was the only time when an accessory was used—a harp, so small that it looked almost ridiculous next to the “real” harp in the orchestra. On top of that, the singer—who sparingly played that instrument, had to go down to her knees. For one, this looked rather odd, and then, that small instrument could barely be heard in the audience (as also the ears needed to adjust to the acoustics of the venue): it would have been far better for the soprano to just sing (standing), and to leave the harp playing to the big (baroque) harp.

Blažiková’s singing was very good: a clear, lucid voice, well-projecting without unnecessary drama. Excellent also her soft singing, her decrescendo from p to ppp. This made the audience focus onto the podium!

The first notes of the Ritornello immediately indicated Gardiner’s preference for “careful”, if not slow tempo: strangely retained. This only possibly made sense to me because of Euridice’s contrasting singing in-between. After all, the prologue isn’t tragic (just yet): it doesn’t need to be happy and joyful. It’s OK for it to be reflective—but why so slow, almost sad?

Act I

Action: Nymphs, herdsmen and shepherdesses celebrate Orfeo’s marriage with Euridice.

The Monteverdi Choir (17 singers total, 6 + 5 + 2 + 4) entered the hall as double procession along the sides of the hall (from the rear), preceded by theorbos. As mentioned, the choir then was mostly (or often) standing behind the orchestra, either singing, or (mostly) illustrating the action, e.g., with dances. The singing in the choir was excellent: to me, the choir offered most of the true highlights of the evening. It was agile, precise, with excellent diction, and an amazing sound, with a volume that easily filled the venue.

Here, the coir was impersonating the nymphs, shepherds and shepherdesses, friends of the central couple. The choir’s initial verse “Vieni Imeneo” was (again) very (too) solemn, slow. Isn’t that supposed to be a happy, joyful wedding? However, that soon changed into joy and happiness with the subsequent verses. Actually, throughout the opera, fast tempi (almost) seemed to be reserved for the choir.

What I didn’t like that much, though, wasn’t so much the dancing, but that the singing was associated with rhythmic, syncopated clapping and stomping. To my taste, this sounded too “popular”, too “jazzy”: it felt as if it intended to animate the audience to start clapping along. A cheap approach to arousing the audience?

Act II

Action: Orfeo is happily resting in nature, enjoying thoughts about how life changed with the advent of his spouse. But a messenger (messaggiera) brings the news of Euridice’s death through the bite of a snake. Orfeo decides to descend into the Underworld.

Messaggiera

The solo singers in general were excellent, pretty much throughout. I liked the voice of the messenger (messaggiera, Lucile Richardot), with plenty of strength and volume, a nice timbre—and dramatic, where needed.

I found it to be an interesting idea to let her start her announcement very softly, ppp, from a distance (outside the rear entry of the hall), like a mere premonition. She then gradually increased her volume and presence (and the certainty of her announcement) while she was walking onto stage. Under Ponnelle’s direction in Zurich, this announcement came as a sudden splash, as a shock. Both approaches can work, though the “gradual solution” is more difficult to realize, is possibly less efficient as a stage event, especially in a semi-stage production.

I mentioned that the costumes were all more or less neutral in color (white — beige — black); the messaggiera was the only exception to this, with her dark red dress. I didn’t quite understand that choice: yes, that message is a very central element in the opera—but, after all, Euridice did not pass away in bloodshed?

Orfeo, Continuo

In general, I found the continuo to be too “fleshy”, in that it tended towards legato (organ, cello and/or double bass), such as to create a constant and permanent bass foundation. With this, some of the transparency was lost, and in addition, it created a certain monotony in sound, almost throughout the evening. Also, with this foundation, one could barely hear the cembali.

Orfeo (Krystian Adam) had an excellent, voice with a wide range of expressions and colors. But he did not dominate the opera, rather often chose a subtle volume, occasionally almost sotto voce. In general, that choice (also a p, even pp, can be intense!) is certainly legitimate. The problem (in my view) was, that in connection with the strong continuo foundation, this caused his voice to lose weight, relative the other voices.

Pain — Dissonances?

One of the—somewhat unfortunate—tendencies in Gardiner’s interpretation is that he avoided pointing out dissonances. Monteverdi often uses these as expression of extreme pain. This wasn’t merely a question of volume, but the permanent continuo, the “rich harmonic filling” also tended to attenuate the effect of such dissonances. For sotto voce singing, a single lute or harp (a rare occurrence here!) would have sufficed as accompaniment & continuo. I don’t think one should take the “continuo” (continuous) aspect too literal!

What certainly stood out in this act was the “Ahi, caso acerbo!” verses, sung by the choir. This was excellent, even though certainly not too dramatic or too fast: some of the mourning music (certainly the last ritornello) was very elegiac, slow (too slow?).

Act III

Action: Orfeo manages to make Caronte (Charon) fall asleep and enters the Underworld.

Orfeo

From the point-of-view of singing, this is Orfeo’s central act. Initially, as he entered the gate to the Underworld, he was singing rather softly—maybe to indicate fear, uncertainty? At times, I almost had the feeling that the voice was too small for the venue. However, later, as he singing Caronte into sleep, he definitely reinforced his vocal presence: a strong scene, with excellent singing, especially in the melismas, the rich ornamentation. That also holds true in soft segments: sometimes, Adam took back his voice to the must subtle ppp. With this, Monteverdi was indicating the most artful singing possible! This aria was accompanied with an excellent, expressive and equally richly ornamented solo on a violino piccolo (Kati Debretzeni, concertmaster), as well as cornettos.

In the aftermath, I had the impression that perhaps Krystian Adam was initially trying to save his voice, to ensure the presence of sufficient reserves for upcoming key segments? After all, that act and his role in it are very long and demanding! As an aside: here, the harpist in the orchestra was playing, rather than the singer. Why did Gardiner not select this option in the prologue?

Other Roles

Speranza (hope, Kangmin Justin Kim) sang from the stage gallery: an excellent countertenor voice, appropriately authoritative, outstanding in firmness, and also in the (proper, early baroque) ornamentation! The most impressive voice of the entire evening, however, was that of Caronte: Gianluca Buratto instantly captured the podium and everybody’s attention with his dominating bass voice.

In the closing choir, the chorus of spirits, the continuo occasionally played staccato—where it had the least effect. The Monteverdi choir shone with excellent, homogeneous voices

Act IV

Action: Touched by Orfeo’s singing, Proserpina convinces her husband Plutone to release Euridice. Plutone agrees under the condition that Orfeo does not look at his spouse while in the Underworld. While guiding Euridice back into life, Orfeo can’t resist: he does indeed look back, losing Euridice forever.

Proserpina

Among the soloists, the role of Proserpina (Francesca Boncompagni) was maybe one of the smaller voices (certainly not bad, though!). But then, she only has the initial and a shorter, second solo. I think that in a concert or semi-scenic performance, voices tend to get more focus. They are more exposed, as there is no distraction from acting & scenery.

Plutone

Plutone is Gianluca Buratto’s second role—just as impressive as Caronte in Act III!

Orfeo & Euridice

This act features another, intense role for Orfeo. It’s the very central scene in the underlying story, when Orfeo can’t resist looking back to see whether Euridice is following. Prior to the mishap, Orfeo has one of the few happy and joyful solos, at last with light articulation and accompaniment. The subsequent hesitations, the temptation, the uncertainty, the scare, all were really well-done. The a frightening moment of the look backwards, the central tragedy, was underlined with exclamations of the choir, and by a sudden light spot onto the scene. That lighting was a tad late, though. Yet, in general, I found the lighting concept good, well-suited for the venue, where the white walls are ideal for color projections.

The moment of separation, Euridice (Hana Blažiková, who also sang La Musica in the prologue), has her only, very short solo—the shortest role in the entire opera: all other singers, including most of the spiriti (and earlier, the pastori) have longer roles.

The choir sang the concluding chorus of the spirits very firmly, at a measured pace: in a way, it felt like a lesson, somewhat ex cathedra. However, that actually (and ideally) fits the text (“Virtue is a ray of heavenly beauty, prize of the soul, … “).

Act V

Action: Apollone finds his son Orfeo mourning his loss; he guides him into Heaven, where he supposedly will find his Euridice again.

The final act is another one where Orfeo does most of the singing. There was again the slow Ritornello that already opened the prologue. Here, the slow pace might be appropriate. Does that imply that the initial instance should be played at the same, slow pace?

In Orfeo’s long, sad, expressive solo (brilliantly performed by Krystian Adam, with excellent sotto voce singing!), there is an occasional, distant echo (eco, sung by Gareth Treseder, tenor). ( With Ponnelle / Harnoncourt in Zurich, the echo was sung by the voice of Euridice: possibly an alteration of the score—but an obvious one, one which makes sense, dramatically. )

In my view, a minor “flaw” was that the voice of Apollone (Furio Zanasi) was very close in volume and character / timbre to that of Orfeo: I see Apollone more a s a fatherly / senior figure (though one might argue that they are father and son, hence should have similar voices).

The concluding Coro dei Pastori (chorus of the shepherds) was again associated by dancing, clapping and stomping (see above). For one, I didn’t like the clapping and stomping by principle. Then, while there are aspects of happiness in the ending, in a way it is more of an apotheosis than a simple happy ending (as in a comedy). Under that perspective, the clapping and stomping (to me) is too earthly, too banal / trivial.

Conclusion

In contrast to Monteverdi’s other two, surviving operas (“Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria“, “L’incoronazione di Poppea“), the score is quite complete, the instrumentation essentially known—with the usual freedom in setting up the basso continuo. For as much I could see, the instruments were either historic or replicas of historic instruments. The playing practice / technique, the ornamentation (such as the execution of tremoli / trills) follows today’s insight in historic performance, was exemplary even. The voices were excellent throughout, Buratto’s (Caronte / Plutone) was spectacular in volume and character, Adam’s in expression, sotto voce and differentiation.

One question I asked myself was, whether for this venue the size of the ensemble should have been adjusted? For sure, Monteverdi could not dream of such a large hall! Also adjusting the articulation would have helped achieving more clarity / transparency in this venue. The White Hall in the KKL features excellent (adjustable) acoustics and sufficient transparency. However, it was mainly the choir who produced a real forte. As a general observation, Gardiner’s interpretation (with the exception of the choir) seemed to aim for subtlety and differentiation in the pp to mf scale. And to the “internal” tragedy, rather than “big scale drama”.

Summary

To summarize: the performance was well-received by the audience. To me, it was too much focused on harmony, beauty of sound. Was it even excessively focused on pleasing the audience? From my perspective, it was certainly anything but radical!

Addendum

For the same concert, I have also written a (shorter) review in German for Bachtrack.com. This posting is not a translation of the Bachtrack review, the rights of which remain with Bachtrack.com. I created the German review using a subset of the notes taken during this concert. I wanted to enable my non-German speaking readers to read about my concert experience as well. Therefore, I have taken my original notes as a loose basis for this separate posting. I’m including additional material that is not present in the Bachtrack review.