Julia Becker, Giovanni Antonini / Tonhalle Orchestra

Haydn / Mozart

Tonhalle Zurich, 2017-07-05

2017-07-13 — Original posting

Abschied von der Alten Tonhalle mit Mozart und Haydn — Zusammenfassung

Giovanni Antonini weiß, wie man auch auf heutigen Instrumenten die relevanten Komponenten der originalen Klangwelt wiederaufleben lassen kann. Das Tonhalle-Orchester ist das ideale Werkzeug dafür! Da wurde leicht und jederzeit klar artikuliert, plastisch phrasiert, Noten (sofern nicht legato) konsequent entlastet, Vibrato schien “verboten”.

Zur Eröffnung Haydns bekannte Sinfonie Nr.101, “Die Uhr”. Der Klang war unheimlich transparent, im Presto-Teil des ersten Satzes dominierte die Spielfreude, kräftige dynamische Kontraste erzeugten einen belebenden al fresco-Effekt, legato-Melodien kamen in diesem Setting besonders gut zur Geltung.

Im “Strassburger” Violinkonzert von Mozart spielte Julia Becker mit Intonationssicherheit; schade, dass sie es nicht wagte, mit wenig(er) Vibrato und mit leichter Artikulation zu spielen, so wie ihre Kolleginnen und Kollegen im Orchester.

Bei Haydns Sinfonie Nr.103 ließ Antonini den eröffnenden, abklingenden Paukenwirbel ins Geschwätz des Publikums fallen. Die nachfolgende Ruhe mit der kriechenden Bassmelodie wirkte beinahe gespenstisch. Dafür erschien dann das nachfolgende, kontrastreiche Allegro con spirito umso geistreicher. Das Andante più tosto Allegretto—schon im Titel ein Zwitter—hat in seiner Vielfalt schon fast Scherzo-Charakter. Eingebettet in diesen Satz ist ein kleines Violinkonzert, das der Konzertmeister, Klaidi Sahatçi, wunderbar feinfühlig und ganz im Stile der Begleitung, sehr leicht artikuliert und sparsam im Vibrato vortrug. Das Finale nahm Antonini in einem anspruchsvollen Zeitmaß. Ein hinreißender, spannender Satz, im Orchester enthusiastisch gespielt, blitzsauber artikuliert. Eine absolute Spitzenleistung zum Abschluss!

Table of Contents

Introduction

So, this was it—the last concert with the Tonhalle Orchestra in the “old” grand hall of the Tonhalle Zurich (with a repeat concert on the following day). The venue is now undergoing thorough renovation / reconstruction. The renovation addresses the entire congress site (Kongresshaus Zürich), whereby some of the more recent add-on parts are removed, in order to make the site more attractive again. Just as important for the Tonhalle (primarily the musicians) are the planned, major improvements to the artist’s facilities. The Grand Hall itself will have its paintings and walls cleaned up and restored to the state in which Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897) still encountered it when it was opened in 1895. Everybody is looking forward to the more vivid and brighter colors.

The will also be a new organ that will presumably be better suited for concerts with orchestra. The current organ (Kleuker-Steinmeyer, 1988) will be sold off. In 2020, when it will celebrate the 125th anniversary, the hall with its 1455 seats will re-open. For the coming three years, the Tonhalle Orchestra will perform its local concerts in a replacement site with 1224 seats (Tonhalle Maag, Zahnradstrasse 22, CH-8005 Zürich) in Zurich-West.

The Last Concert in the Old Venue

This last concert with the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich in the old venue ran under the label “Orchestral Magic” (Orchestermagie). One might expect that this title stood for a program full of highly virtuosic, late romantic or 20th century orchestral showpieces. Naïvely, I also would have expected the still-chief conductor, Lionel Bringuier (*1986), to take this opportunity to perform in this venue for a last time. None of this was the case.

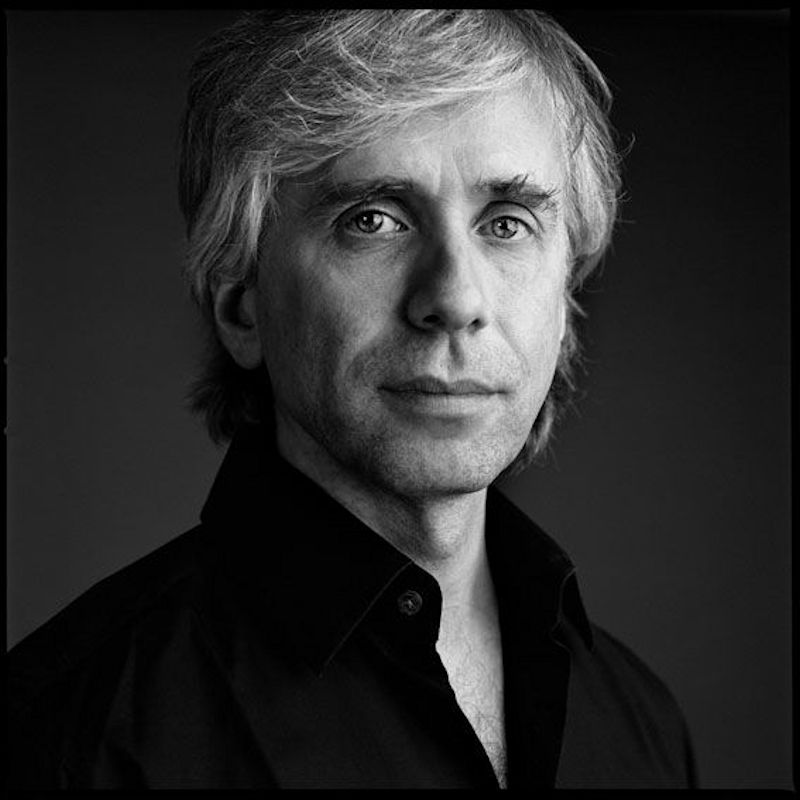

For this (subscription) concert, the orchestra invited a specialist in historically informed performances, Giovanni Antonini (*1965). And the program was a joyful—jaunty, untroubled mix of two symphonies by Joseph Haydn, and a violin concerto by Mozart. This led to a smaller orchestral configuration. The musicians mostly performed on modern instruments; exceptions were the natural, valveless horns and trumpets, and of course timpani with slim drum sticks with wooden heads. And of course, the orchestra used the historically correct placement of the two violin voices facing each other at the front of the podium.

Haydn: Symphony No.101 in D major, “The Clock”

This popular symphony is #9 out of twelve that Franz Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809) wrote in and for London (Symphony No.101 dates from 1793/1794). The nickname is from the second movement, which reminds of the ticking of a clock. The four movements in this symphony are

- Adagio (3/4) – Presto (6/8)

- Andante (2/4)

- Menuetto & Trio: Allegretto (3/4)

- Finale: Vivace (2/2)

The Performance

I. Adagio – Presto

Clearly, Giovanni Antonini knows how to create the essential components of historically correct orchestral sound, even when using modern instruments. And the Tonhalle Orchestra proved to be the ideal tool for this. The musicians used light articulation, the sound was very clear and transparent at all times, the phrasing showed vivid plasticity. Consequently (unless legato was required by the score) notes were discharged, vibrato appeared to be “forbidden”.

The Presto part of the opening movement seemed to express joie de vivre (joy of playing, rather). Strong dynamic contrasts created a vivid al fresco sound, and this setting nicely exposed legato melodies.

Giovanni Antonini conducted without baton, using large gestures with both hands, vivid body language, which pulled along the orchestra.

II. Andante

Antonini kept the tempo in the “clock”-Andante calm, resting in itself. He was very good at keeping it throughout the movement, with an excellent feel for the “right” pace. Yet, at no point there were signs that the orchestra’s attention or the tension would weaken in any way. It was also obvious how much care Giovanni Antonini devoted to detailed dynamics. Also, he kept staccati very short, which made slurs stand out even more.

With the calm first part of the movement, the sudden, dramatic, and often dissonant eruption in the middle part turned out particularly scary. This was ff rather than just f, and reinforced by vehement drum beats. Clearly, the composer was having fun with “waking up” his audiences! The movement returns to the innocence of the beginning—but then there is this surprising general rest that makes listener believe that the movement ended. However, this is followed by a new start with a surprising, new tonality. A synthesis of the dramatic part and the serenity of the “clock” theme follows, with the strong accents that make this sound like a caricature. The joking Haydn at his best!

III. Menuetto & Trio: Allegretto

A placid, comfortable Menuet would not have been the right continuation! Here, this definitely sounded more like a Scherzo, with its jaunty pace. The light articulation contrasted to the fairly strong, mocking syncopes.

The Trio was strikingly faster, just as vivid and Scherzo-like as the Menuetto. Even the Trio featured short, dramatic interjections, but innocently died away in pp, before the Menuetto returned.

IV. Finale: Vivace

The final movement takes a gentle, innocent start, almost appears to be in danger of losing tension over the two repeated segments—but then a sudden, strong f erupts, with vehement ff accents and intermittent sections with the innocent theme from the beginning. After modulations and fermata, a demanding fugato follows, which reveals the real qualities of the orchestra, with excellent coordination and perfectly clear articulation. Orchestral magic, really!

Mozart: Violin Concerto No.3 in G major, K.216, “Strassburg”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 – 1791) wrote this third violin concerto 1775, when he was just 19 (and an excellent violin player!). The surname “Strassburg” refers to a remark in which Mozart told his father that he had played a concerto in G “from Strassburg” (where he just had been). It is not entirely clear, though, whether he was really talking about the composition that we now know as K.216. This has three movements:

- Allegro (4/4)

- Adagio (4/4)

- Rondeau: Allegro (3/8) — Andante (2/2) — Allegretto — Allegro (3/8)

The Soloist

The soloist in the violin concerto was Julia Becker (*1968), who was the first female concertmaster in the Tonhalle Orchestra, and holding that position for the past 22 years. It was not the first time that she appeared as soloist with “her” orchestra, but still a rare opportunity to present her abilities as solo violinist.

The Performance

I. Allegro

Naturally, the focus in this work was on the soloist rather than on the accompaniment. The orchestra played in a slightly smaller configuration (6 + 6 + 4 + 3 + 2 string players), which made the articulation sound even lighter and more springy.

I liked Julia Becker’s firmness in intonation. And I enjoyed the excellent projection, the beautiful sonority of her instrument, particularly the warm, characterful lower registers. Sadly, the soloist didn’t seem to dare to play with little / less vibrato, and with the orchestra’s light articulation. I should state, though, that historically informed playing still today is a rare exception with the solo part in classic violin concertos. So, HIP playing still requires a fair amount of “guts”, courage. Maybe Julia Becker didn’t want to expose herself more than necessary?

The soloist’s articulation tended towards legato, the vibrato was pretty much omnipresent. At least, it was dosed tastefully, and neither nervous nor exceedingly heavy. And the cadenzas were well-fitting and imaginative, within the scope of the interpretation. Overall, this felt like a conventional interpretation with a somewhat diverging HIP accompaniment.

II. Adagio

Despite the vibrato, the Adagio felt relatively uncluttered. Also here, the articulation was conventional, tending towards legato and a broad portato. The one thing that occasionally irritated was a slight tendency towards “belly notes” and Nachdrücken (swelling towards the end of long notes, prior to changing bow). This can be seen as a natural danger with, if not a consequence of modern Tourte violin bows. A very nice cadenza—not longer than needed in this movement!

III. Rondeau: Allegro — Andante — Allegretto — Allegro

Here, the Allegro parts again exposed the discrepancy between the light, fresh articulation in the accompaniment and the more conventional solo part. Of course, also Mozart could not resist a few jokes! Besides the sassy accents in the Allegro, here it is the sudden transition to a moody, almost melancholic Andante with pizzicato accompaniment, which feels like a page or two from a different concerto. This is not followed by a return to the Allegro, but by yet another, “extraneous” section full of momentum, with hurdy-gurdy tunes. And was it just me who thought of hearing some Turkish “accent” in this part? A general rest follows (here as well!), and then, the Allegro part returns, as if nothing had happened in-between. But even the sudden “suspended” ending must have been one of Mozart’s jokes!

I should point out that the above critical remarks about the soloist’s playing are my personal view. And at no point did this stop me from enjoying the music! People in general really liked this performance: the audience, as well as her colleagues in the orchestra, offered the soloist a long, warm applause.

Haydn: Symphony No.103 in E♭ major, “Drumroll”

The last piece in this concert was #11 among Franz Joseph Haydn‘s twelve “London” symphonies. Haydn composed this 1794/1795. For more information please refer to my separate post on this symphony (comparing two recordings). I also have written about this composition in an earlier concert review from a Philharmonic Concert at Zurich Opera, on 2014-12-14. So, here, I just list the movements with their time signatures:

- Adagio (3/4) – Allegro con spirito (6/8)

- Andante più tosto allegretto (2/4)

- Menuetto & Trio (3/4)

- Finale: Allegro con spirito (2/2)

The Performance

I. Adagio – Allegro con spirito

Giovanni Antonini jumped onto the podium, didn’t even greet the audience, but immediately started with the drum roll, right into the chatting and clapping of the audience. That must be absolutely in line with the composer’s humorous intent to shut off the noise in the audience prior to starting the actual music!

After this surprise start, the silence with the slow bass melody felt almost creepy. This formed a strong counterpoint to the subsequent, witty Allegro con spirito, rich in contrasts. Rather than showing off strength and extra volume, Antonini had the orchestra perform the soft parts particularly subtly, down to pp, which automatically and effortlessly made the joyful, if not boisterous f segments stand out. He seemed to wait extra long in general rests, as if he wanted to add further tension, increase the expectation on what was to follow.

Haydn obviously could not resist adding another joke, by starting the Coda with another—now unnecessary—drumroll, followed by a short version of the opening Adagio.

II. Andante più tosto allegretto

A fairly ambiguous annotation! It’s a movement with diverse faces, overall more of a Scherzo than a “slow” movement—at least at the Allegretto pace in this performance: I think Antonini chose an excellent tempo! The beginning is moody, then, the music brightens up, turns more playful, sometimes feeling like a measured peasant dance.

In the center of this movement, there is a little violin concerto. Here, the soloist was the concertmaster, Klaidi Sahatçi (*1972). He played this with marvelous subtlety, with very light articulation and almost no vibrato, entirely in the style of the orchestral performance—simply excellent! In the aftermath, I felt sorry for Julia Becker: that’s what I would have liked to hear in the performance of the Mozart concerto!

The last part of the movement alternates between harmless play and blustering, stomping moments—and more humor, in surprising modulations and jokingly unexpected general rests. Excellent entertainment, for sure!

III. Menuetto & Trio

Musically, the Menuetto felt far more well-behaved than the preceding movement, even though it has stomping periods, where it reminds of a peasant dance. Overall, Antonini chose a rather fluent tempo, avoiding making the music sound too heavy. I particularly enjoyed the mellow, very pure and gentle sound of the clarinets in the Trio.

IV. Finale: Allegro con spirito

Finally, the last movement saw a rather challenging tempo. However, the orchestra performed with flawless, clean articulation. The music was enthralling, full of tension, momentum and drive. And the orchestra played with obvious joy and enthusiasm: an absolute highlight, a top-level performance to end this evening and the Tonhalle Orchestra’s concert season: congratulations!

Addendum

For the same concert, I have also written a (shorter) review in German for Bachtrack.com. This posting is not a translation of the Bachtrack review, the rights of which remain with Bachtrack.com. I created the German review using a subset of the notes taken during this concert. I wanted to enable my non-German speaking readers to read about my concert experience as well. Therefore, I have taken my original notes as a loose basis for this separate posting. I’m including additional material that is not present in the Bachtrack review.