Authenticity and Originality —

Antagonists in Music Interpretation?

A Reflection / Personal Thoughts

2018-10-02 — Original posting

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- A Purpose Beyond Casual Entertainment?

- How Does the Composer Do It?

- Authenticity?

- An Illusion Anyway?

- Authenticity, Originality in Music Re-Creation Today

- Re-Creation and Originality

- Originality—Indispensable!

- Perception of Authenticity

- The Listener’s Expectations

- Anything goes?

- Where are the Limits?

Introduction

If we exclude music that is fixed / defined purely electronically (like a computer program producing sounds, or playing a MIDI file), all classical music necessarily is interpretation. Artists read the score. From the composer’s notation, in the moment of the performance, they re-create the music, i.e., the composition, the composer’s invention.

One may try fixating, “freezing” the act of a performance into an audio or audiovisual recording. However, ultimately, each and every interpretation remains unique, a product of the circumstances at the moment of the performance. With every performance, consciously or subconsciously, artists, (active / critical) listeners, as well as critics are confronting the question “Is this (still) the composer’s intent?”. This leads into the related question about the purpose to performance / interpretation:

A Purpose Beyond Casual Entertainment?

Implicitly at least, this question affects, concerns artists, critics, as well as critical listeners.

Sure, music wants to entertain, to create joy and pleasure. However, at the same time, it enriches, exhilarates, delights, touches, motivates, it provokes thoughts, stirs up feelings / emotions, it offers solace, comfort, fun. And it may make us dance, cry, or laugh. Depending on the composer and the actual work, music does this by talking to our emotions and senses, but also to the intellect. Mechanistically, it achieves these effects through musical constructs such as texture and form (overt or hidden to the listener), but of course also through underlying text.

How Does the Composer Do It?

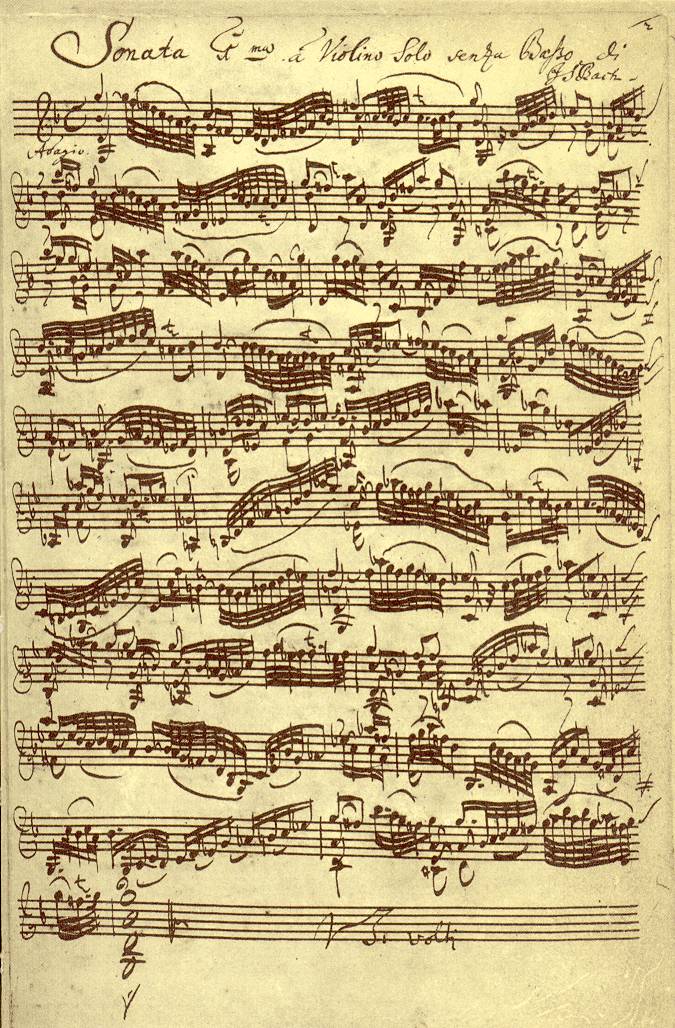

Music as the creation of a composer originates as a spontaneous invention / inspiration. But it is equally the result of an intellectual effort. The biggest proportion of this consists of trying to fix, to distill that invention into musical notation. With some prolific people such as Bach or Mozart, that second step occurs entirely in the composer’s mind. For other creative minds, Beethoven being a prime example, this was (or is) a lengthy, painful process. One can see this as attempt to catch as much as possible of the spontaneous, maybe foggy, inspiration, to concretize it into musical notation, to cast it into a score.

The text in the score acts as an abstract, imperfect means of transport for musical content. Even in the case of composers who did their utmost to fixate every tiny detail of their creations (e.g., Gustav Mahler, or composers of the Second Viennese School), the score remains an incomplete image or projection of what the composer had in mind.

Authenticity?

With this, “true, proper authenticity” can’t exist, unless composer and performing artist are one and the same. This could be a composer performing his or her own works. Another example would be an artist improvising, i.e., “composing on the spot”. This implies creating a new, unheard work in the very moment of the performance, out of the spirit of the moment, using a combination of imagination and mind.

One can take for granted that the composers are aware of the limitations of musical notation. But we also must assume that composers write their scores with sufficient accuracy and detail, such that the notation contains / includes what they regard as essential, as the essence of their creations.

For many composers, the knowledge about the inherent shortcomings and limitations of musical notation is a severe impediment in the creative process. One can see this from the countless revisions from the first draft to the final, published version. One example for this is Anton Bruckner. The awareness about the limitations in notation can be particularly painful for composers. With the publication of a new work, they ultimately lose control over their creation, exposing it to the uncertainties, the arbitrariness of interpretation by subsequent recreating by artists.

An Illusion Anyway?

Of course, composers have even less control over what recipients, i.e., concert audiences, listeners, feel when listening to their music. Worse than that: musical impression is subject to change over time. Simply put: to a composer, publishing a work always means that one must “let go” the creation, set it free, say farewell to it, expose it to the imponderabilities of music life with future generations. That said: this farewell may be painful. However, it can also produce the feeling of relief.

One might claim that with this, authenticity remains wishful thinking. One could see it as attempt to get hold of the composer’s suspected / assumed intent. Or maybe (also) as an attempt to reconstruct or reproduce alleged impact of a composition on audiences at the time of the composition. Musicology plays a key role in the attempt to define hypothetical authenticity:

- What were the musical / instrumental practices at the time of the composition?

- How about the musical and societal surroundings (in specific local circumstances)?

- What was the composer’s intent?

- How did a composition sound at the time of the creation? And how did it (possibly) sound in the composer’s mind / imagination?

- What was the effect of a composition on listeners at the time of creation? Under specific circumstances / surroundings?

It’s amazing how much in all this we still don’t know (and very likely will never know). And a lot of this is subject to heated debates among musicologists, artists, and interested listeners.

Authenticity, Originality in Music Re-Creation Today

As outlined above, in the strict sense, authenticity doesn’t even exist in musical performances. Yet: if the “label declaration” (a.k.a. concert program, CD booklet, etc.) states “Chopin”, then I expect exactly that, i.e., how I expect the music of that composer to sound, based on prior knowledge, sources such as scores, information about the composer and musical practice in his/her time, etc.

Such expectations also depend things such as current musical taste & preferences, local “fashion”, musical surroundings in general. There are no universal and lasting answers to questions of authenticity.

Expectations also greatly vary depending on whether a performance is using original (or historically reconstructed) instrumentation, or whether modern instruments are used (examples: fortepiano or harpsichord vs. modern concert grand). Obviously, the definition of authenticity is much narrower in the case of historically “correct” instrumentation.

Re-Creation and Originality

Musical Performance always involves re-creation (a partial re-composition), hence requires originality through the creativity of the performing artist. On top of that, an indispensable component in the effect of music is in the interaction between the reproducing artist(s) and the recipient. With this, the effect of music is a product of the momentary circumstances. Therefore, it must be elaborated, newly acquired with every performance.

At the same time, the effect of music depends on the actual surroundings, such as acoustics, the mood and temper of both artists and recipients, plus external influences such as weather, temperature and humidity, physical well-being, receptivity and distraction from daily life, fears, pains, even the political situation may play a role. To some degree, this is also valid for studio productions. Irrespective of whether an artist is playing for him/herself, for recording engineers, or for an imaginary audience.

Originality—Indispensable!

With this, originality truly is an indispensable aspect of any “living” musical performance, both in concert, as well as in the studio. Music as strict, “mechanical” reproduction of an imagined, “authentic original” would be dead, would miss its goal, cannot exert its intended effect.

This opens up the field of a multifaceted, living music culture and concert scene. It goes without saying that no artist can claim to offer the single, correct version of any composition. That said, performing classical music remains a question of sense of proportions. The artist must find a sensible balance between

- authenticity, i.e., being truthful to the composer the alleged / assumed intent of the composer, i.e., the effect the composer presumably meant to achieve with the listener—and

- trying to reproduce this intended effect on today’s audiences, today’s surroundings / music life, with the help of originality.

Perception of Authenticity

With all this, decisions on how to re-produce the composer’s intent are subject to considerable fuzziness. And so, there is a substantial bandwidth in most of all aspects of performing classical music today. Actually, that variability has always existed. It’s just that in a time of electronic media, the countless festivals, the intense traveling of artists and ensembles, orchestras, we are becoming much more aware of that bandwidth.

In all this, what is still “legitimate”, i.e., where are the boundaries of authenticity? Clearly, there is no general, universal answer to this. Everyone must decide for themselves.

Over time, musicians develop personal views / interpretations. Actually, with every performance, they decide anew, how and to what extent they want to convey the (assumed) intent of the composer. And how much freedom they allow themselves. At a time where freedom of speech and freedom of opinion is on everybody’s mind, one should assume many things, if not everything is possible and permitted. At least, as long as it does not offend others, and/or, as long as a performance does not transgress legally binding restrictions. The latter may exist with living / contemporary composers, or with works under specific copyright restrictions.

The Listener’s Expectations

In my opinion, one should not be too narrow-minded in one’s expectations about an artist’s performance. Especially in the first encounter with an artist. One should be open for the artist’s personal nuances and preferences. Over time, concert audiences go through a learning process. Over time they acquire some familiarity with the peculiarities of a specific artist.

As outlined above, in this interplay between expectation and the actual performance, there will always be a considerable bandwidth. At the same time performances and expectations will evolve along with the general “feel”, the taste, fashion trends. These affect almost all aspects of music performance and reception. There is even mutual influence between these. Among others, the affected performance aspects include

- tempo

- vibrato, portamento

- articulation: legato, portato, staccato

- instrumentation:

- modern vs. historically informed vs. historic, including

- strings (gut vs. polymer/steel),

- bows (modern/Tourte vs. baroque or classical),

- fortepiano vs. modern concert grand,

- harpsichord or piano,

- tube dimensions in wind instruments,

- natural vs. valve horns

- playing techniques (bowing, fingering / hand positioning, blowing, articulation, pedaling)

- orchestral arrangement: modern or romantic, sitting vs. standing

- acoustics, size of the orchestra, size of the venue

- use of electronic or acoustic aides

Anything goes?

All these variables above by no means imply that “anything goes”, i.e., that everything is permissible, let alone desirable. As a consumer of electronic media, I can usually preview a performance before buying, or in streaming sites I can opt out any time. This has no or little effect on the artist, but at least, it prevents disappointments.

As for concerts: one should keep in mind that people in the audience are paying fair amounts for their seats. And from this, prominent artists often receive substantial fees for their performances. So, as a concertgoer, I personally expect that at the very least, a performance is not in gross disagreement with the composer’s legacy and instructions (the notation in the score, the autograph, and/or knowledge about traditional/historic, specific playing instructions & techniques). Specifically: if a concert program announces an artist with the work of a particular composer, then I assume that the compositions announced are recognizable as such, e.g., in that tempo and other annotations in the score are observed at least approximately.

Where are the Limits?

It goes without saying that it is not forbidden to interpret a composition very freely, with personal variation, ornamentation, embellishments, as “fantasy over…”, or parody (the proper technical term for this in baroque times). Such personal interpretations, adaptations, parodies were very common already in medieval and baroque times. However, in this case, the program should preferably not read “work X by composer Y”. Rather, the announcement (ideally) should mention “personal fantasy / variation(s) of the artist about work X by composer Y”.

This way, as a concertgoer, I can prepare myself for what I’m going to hear. Hence, I can avoid feeling disappointed or even betrayed in my expectations. This is especially true if this is my first encounter with an artist, or with an artist playing music by a specific composer. Sure, next time with the same artist(s) I’ll be pre-warned by previous experience, but still…

As stated above, over the years, concertgoers, music listeners / recipients in general will develop personal preferences. And hopefully, that personal taste will grow, evolve over time. In this process, I suggest retaining some tolerance towards other and new opinions. There are no strict, globally valid, eternal rules about how classical music ought to be played and heard.

A Final Note

This article was suggested by Migros-Kulturprozent-Classics. Thanks for the suggestion: it’s a topic that I have had in mind for a while already!

The original, German version of this text is also available in this blog. This is not a strict translation, but slightly adapted.