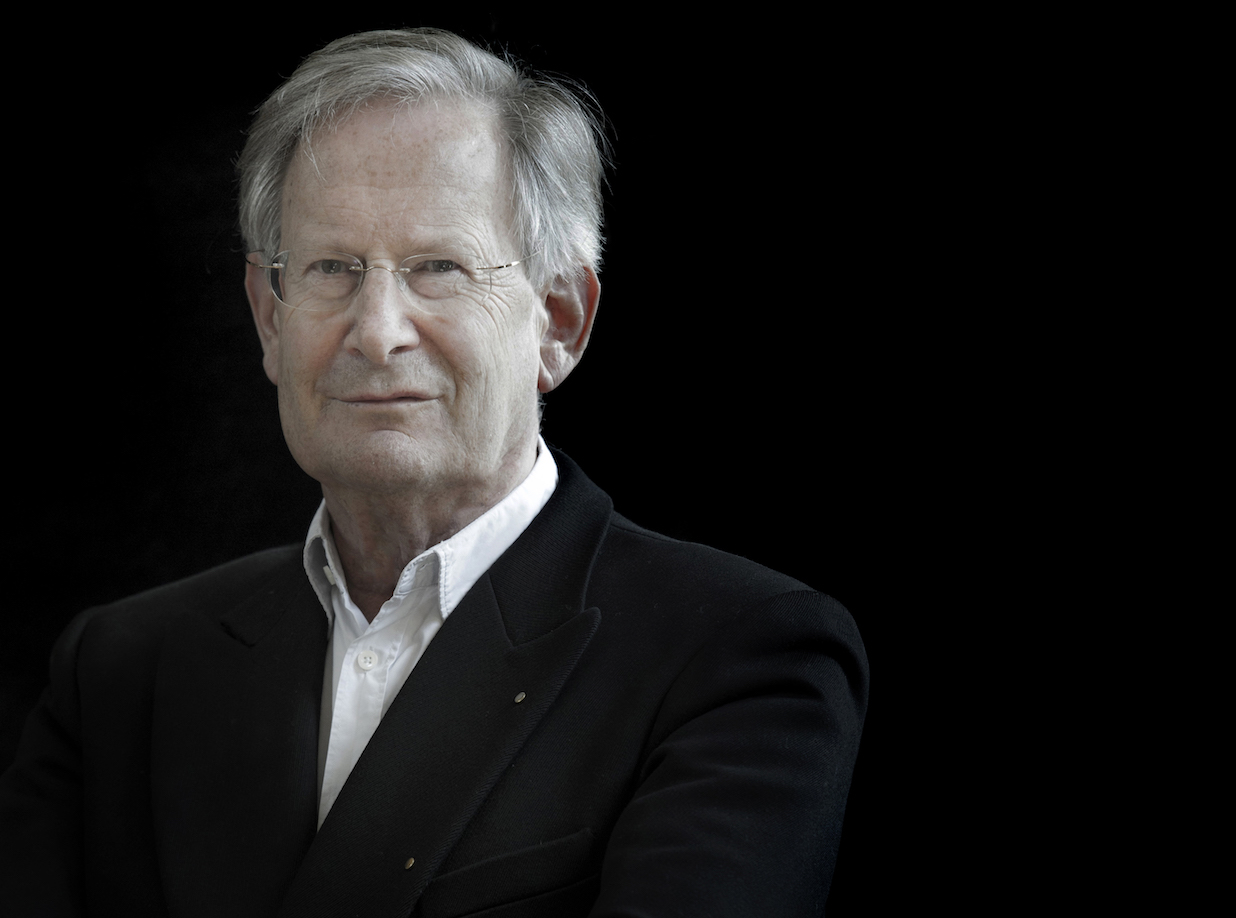

Sir John Eliot Gardiner / ORR, Monteverdi Choir

Verdi: Messa da Requiem

Lucerne, KKL, 2018-10-30

2018-11-16 — Original posting

Verdi’s Messa da Requiem, ein solider Wert in der Konzertliteratur — Zusammenfassung

Durch die Vorwegnahme des pppp Beginns in den Celli, gefolgt von einer langen Pause erreichte Sir John Eliot Gardiner absolute Stille im Konzertsaal.

Im “richtigen” Beginn setzte dann der Chor ein, mit erstaunlicher Sonorität selbst im vierfachen Piano. Während des ganzen Werkes überzeugte der Chor mit Klarheit in Diktion, Aussprache und differenzierter Dynamik, gelegentlich—Gardiner zeigte seine Handschrift—mit überdeutlicher Artikulation. Erst ganz zum Schluss hin waren im Chor minimale Ermüdungserscheinungen, ein leichtes Nachlassen der Spannung, der Aufmerksamkeit zu orten.

Das Orchester intonierte meistens makellos (die “unsichtbaren” Trompeten im “Tuba mirum”, waren leider deutlich zu hoch gestimmt). Die Musiker agierten aktiv, koordiniert, aufmerksam, sehr klar in Dynamik und Artikulation. Auch mit dem historischen Instrumentarium erreichten sie eine eindrückliche Klangfülle.

Die Vokalsolisten fügten sich im Quartett zu einem stimmlich gut ausgewogenen Ensemble zusammen. Die Stimme der Sopranistin, Corinne Winters, zeigte ausserordentliches Volumen, mit dramatischem Vibrato. Im Quartett hatte sie letzteres eher unter Kontrolle. Ann Hallenbergs Mezzosopran war im Timbre, in der Diktion wie Artikulation exzellent. Edgaras Montvidas’ Tenorstimme fehlte es etwas an Glanz und Projektion. Diktion und Ausdruck von Gianluca Burattos Bass waren ausgezeichnet, die Klangfülle seiner Stimme gab dem Soloquartett einen soliden Boden.

Table of Contents

Introduction

This is the second concert of the season that the Foundation Migros-Kulturprozent-Classics has organized. After the first concert in Zurich, on 2018-10-25, this one took place in the concert hall of Lucerne’s KKL (Culture and Convention Center Lucerne). The concert was sold out, which indicates the excellent reputation of the artists (see below). But at the same time (probably even more) it proves the popularity of the single work that was performed, Giuseppe Verdi’s Messa da Requiem.

In several ways, this was a re-encounter with a work that I like and know fairly well:

- I have given a detailed review of a DVD from a ballet performance at the Zurich Opera; in addition,

- I have participated in a performance as a member of a choir, and

- from that same time, I also have LP recordings of the Messa da Requiem — though I haven’t listened to these recordings in decades.

My wife and I had seats on the right-hand side, in row 2 of the fourth (top) balcony—an opportunity to check the acoustics from the “upper rear corner”.

Artists

One work that Sir John Eliot Gardiner (*1943, see also Wikipedia) is/was touring with Verdi’s Messa da Requiem, one of the most popular vocal / choral works of the late 19th century. At the center of the performance—naturally—Gardiner directed his own orchestra for the romantic repertoire, the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique. And, of course, Gardiner came with his own choir, the Monteverdi Choir. From the name, the latter doesn’t seem to fit the romantic repertoire. However, as one of today’s leading choirs, it has a wide-spanning repertoire, covering essentially the entire choral literature, from (pre-)baroque up to romantic music, and beyond.

Gardiner had the orchestra perform in a semi-circular arrangement, with the 12 + 10 violins on the left, followed by 8 violas, to the 7 cellos and 5 double basses on the right. Further back, on slightly rising semi-circular rows, the wind instruments sat between the two percussionists (bass drum / gran cassa, timpani). The choir (19 + 19 + 15 + 15 singers, the female voices in the center) filled three rows at the rear of the podium.

Soloists

While the choir is at the center of Verdi’s Requiem, the four vocal soloists play an almost equally pivotal role:

- Corinne Winters, soprano

- Ann Hallenberg (*1967, see also Wikipedia), mezzosoprano

- Edgaras Montvidas (*1975, see also Wikipedia)

- Gianluca Buratto, bass

All four of these soloists performed by heart, and next to the conductor. In my view, this alone was a tremendous benefit for the performance. It made the singers communicate with the audience directly (supported by gestures), rather than singing into a score in their hands.

Giuseppe Verdi (1813 – 1901): Messa da Requiem

Giuseppe Verdi (1813 – 1901) composed his Messa da Requiem in memory of the famous Italian novelist Alessandro Manzoni (1785 – 1873). The first performance took place in 1874, one year after Manzoni’s death. It’s one of the biggest settings of the catholic funeral mass ever, requiring a large orchestra (3 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 8 trumpets, 3 trombones, Ophicleide, timpani, bass drum, strings), four soloists and double choir. The composition is well-known, so I don’t spend more text on describing it. I’m just giving an outline of the structure:

- Requiem (chorus, soloists)

- Requiem aeternam

- Kyrie eleison — Christe eleison

- Dies Irae

- Dies irae (chorus)

- Tuba mirum (chorus)

- Liber scriptus (bass)

- Dies irae (mezzo-soprano, chorus)

- Quid sum miser (soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor)

- Rex tremendae (soloists, chorus)

- Recordare (soprano, mezzo-soprano)

- Ingemisco (tenor)

- Confutatis — Dies irae (bass, chorus)

- Lacrimosa (soloists, chorus)

- Offertorio

- Domine Jesu Christe (soloists)

- Hostias — Quam olim Abrahae (soloists)

- Sanctus (double chorus)

- Sanctus

- Benedictus

- Hosanna

- Agnus Dei (soprano, mezzo-soprano, chorus)

- Lux aeterna (mezzo-soprano, tenor, bass)

- Libera me (soprano, chorus)

- Libera me

- Dies irae

- Requiem aeternam

- Libera me

The Performance

I. Requiem

Gardiner wanted to have absolute silence for the beginning—so, he had the cellos perform the initial, descending pp (rather pppp) chord—then stopped and waited for half a minute… maybe a little gross as a measure, but effective!

Requiem aeternam

The “proper” beginning was really pppp, and it stayed at that level up to the murmured Requiem in tenors and basses, in which the last syllable almost disappeared. The choir sonority in that extremely soft beginning was excellent. Even at that volume, the “Gardiner handwriting” was obvious: the punctuations in the choir were at the limit of being too clear, too obvious. For example, in Et lux perpetua, the (over)punctuation on lux made the “per” in perpetua sound like an accent, especially in the last instance.

Needless to say that pronunciation and diction were clear and careful. The question of course was: how’s the Latin? How (appropriately) Italian is the pronunciation (for a historically informed performance, I would certainly expect an “Italian tone” in this work). It may be a bit pretentious to make remarks about the pronunciation at this point, but still: I noted that the “e” and “i” vowels in the female voices were a tad (too) open. That continued (even more noticeable) with the three “e” in Te decet hymnus—it seems hard to eliminate non-Italian coloring!

In line with the previous remark above, dynamics and articulation seemed over-clear, almost “technical”. At the same time (of course), the intonation was flawless, the choir sonority simply excellent, stunning in the intended “wake-up moment” in the crescendo transition to the Kyrie.

Kyrie eleison — Christe eleison

I’ll comment on the soloists primarily with their prominent solo and duet performances. Here, I found the quartet to have excellent balance and projection. It paid to have them perform at the front of the podium: sound and diction were clear. Maybe the soprano was somewhat on the “dramatic side”—but Verdi is an opera composer, first and foremost.

★★★★

II. Dies Irae

Dies irae —

Gardiner made the Day of Wrath break in with brutal force and acuity, the semiquaver cascades were shooting down like a tumbling meteor (or a ride to hell?). The brutality in the subsequent beats was even more intense through the addition of the dull, dark beats of the gran cassa, almost aiming directly at the listener’s stomach! Not just the orchestra was dramatic, but the choir, too—while maintaining excellent diction and pronunciation.

★★★★½

Tuba mirum —

“Trumpets from everywhere”—Wondrous sound the trumpet flingeth (the call before the throne)—four trumpets in the orchestra are complemented by four at a distance, from behind the scene (in lontananza ed invisibili). The 3D-effect of the soundscape was impressive—sadly, however, the instruments at a distance (from the rear of the audience) were all tuned very noticeably too high. That could not have been the intent, can it? I found this badly irritating. It almost made me wish for the situation some 40+ years back, in Zurich, when to everybody’s dismay, the four distant trumpets remained absent for the entire passage. Unfortunately, it is impossible to correct the tuning prior to the ff Tutta forza, unless one wanted to interrupt and start over.

★★★

In its own way, the Mors stupebit in the bass solo was just as scary as the eruption of the Dies irae: frightening, with Gianluca Buratto’s dark voice talking into a trembling silence.

★★★★

Liber scriptus — Dies irae —

Excellent, extraordinary, Ann Hallenberg’s mezzosoprano voice! Her volume and range, her timbre, as well as diction and articulation are outstanding: excellent projection also at the low end, very (but not overly) dramatic in the heights.

★★★★½

Equally excellent: how Gardiner made the choir almost whisper the Dies irae—annotated sempre cupo e pianissimo—up to another, violent eruption. The latter, this time, not with drum beats, but trembling from strings and percussion.

★★★★

Quid sum miser —

Here now, the tenor and the soprano joined Ann Hallenberg. Compared to the other two, Edgaras Montvidas’ tenor voice seemed to lack projection and radiance. I actually asked myself whether he was indisposed or otherwise not in top shape for this concert. (★★★)

Corinne Winters had excellent range, projection and volume—her vibrato was dramatic, but at least here, it suited her part. She seemed to have a certain tendency towards soft transitions, and to approach high notes from below. The part is very challenging and often highly exposed, though.

★★★★

Rex tremendae —

Excellent, this rolling “r” in the basses, as well as sonority and diction in the 3-part split tenors. The choir in general was excellent here (★★★★½)—as was Ann Hallenberg (★★★★★), while the tenor appeared to lack some “ping” in his voice.

Recordare —

This offered an opportunity to hear the two female soloists side by side. While in their volume and projection, they seemed to match well, the mezzo voice was clearer, better defined, while the intonation in the soprano never reached the clarity and definition of her colleague’s voice, even though she clearly has the required tonal range.

Ingemisco —

Hmmm, why, why “Inguemisco“??? Why in such an exposed moment? It sounds so un-Italian!!! Apart from that initial flaw, though, Montvidas’ performance was not bad at all in this section, which is very challenging with the messa di voce, and the required subtle diminuendo. Sure, a little more “ping” would be even better, and it would also help making the dolce even softer…

★★★★

Confutatis — Dies irae —

Truly excellent bass performance: expressive, full voice, projection and volume—effortlessly, Buratto caught and kept the attention, also in the lyrical dolce segments, and even in the sotto voce of the Oro supplex et acclinis (★★★★½)! The orchestral interjections, and even more so the subsequent, third Dies irae, were maybe even more incisive, sharper than the initial instance.

★★★★★

Lacrimosa

In the Lacrimosa, mezzosoprano and bass voice were perfectly matched in volume and expression. When the other voices joined them for a quartet, the soloists formed a well-balanced ensemble, and also the soprano showed better voice control than earlier on. The quartet was particularly impressive in the intense prayer of the Pie Jesu.

★★★★½

III. Offertorio

Domine Jesu Christe —

Excellent duet with tenor and mezzosoprano—though the cantabile of Gianluca Buratto’s Libera animas seemed to overshadow the two.

★★★★½

The entry of the soprano is excruciatingly difficult, starting pp, then a long messa di voce, instantly back to ppp—and it wasn’t a full success, and in the subsequent signifer sanctus Michael, her vibrato affected the intonation.

The first Quam olim Abrahae (and the transition to it) felt a tad technical, maybe lacking some Italianità in rhythm and expression?

Hostias — Quam olim Abrahae

In the tenor solo Hostias, Verdi asks for dolcissimamemte and pp. Edgaras Montvidas started with a covered sotto voce, which to me is not the same as the annotation. Sure, towards the laudis, he added “ping”. My personal ideal for this has “ping” also in the pp, and it could be even more expansive in the climax. The bass showed a more balanced approach, with better voice definition across the volume span. The tenor temporarily returned to sotto voce, and the intonation then was not quite ideal. I was sometimes also longing for some more “Italian” agogics (more ritenuto at peak notes, etc.).

In this music, choir and vocal soloists easily capture all of the listener’s attention. I should definitely mention that the orchestra was not just excellent in the eruptions of the Dies irae, but actually throughout the entire performance (if we ignore the “trumpet mishap”): the attention, the active participation, coordination, intonation (!), dynamics and sound were all more than remarkable. How could the sound be any better, with all the period instruments? In the Offertorio, the diminuendo, and the sound quality in the final ppp morendo were simply breathtaking!

★★★★★

IV. Sanctus

Here now, Gardiner did not wait for silence, but interrupted the coughing in the audience with the trumpet signal. These initial fanfares felt like a wake-up call. What follows is a complicated, virtuosic, 8-part fugue for double choir. Needless to say that the performance was flawless in both the choir(s) and the orchestra.

I have no reservation whatsoever about the technical aspects of the performance. However, I think that the real challenge in this movement is not the technical aspect per se, but rather in how to make this appear effortless while at the same time retaining the “atmosphere of holiness”, of the mystery of faith. It’s definitely more than a virtuosic showpiece, even where it breaks out in trumpet fanfares, maybe even in the brilliant, accented / syncopated ending?

★★★★

V. Agnus Dei

Here, the two female soloists moved back, to a position between the conductor and the choir. I found their beginning somewhat technical: e.g., the two acciaccaturas were slightly too obvious, almost fabricated, rather than a subtle ornament / illustration. Lacking depth? The choir was more expressive, solemn, begging than the soloists.

★★★★½ (choir) / ★★★½ (soprano) / ★★★★ (mezzosoprano)

VI. Lux aeterna

The initial terzetto of the soloists (MS, T, B) was excellent, even though I could have imagined a slightly slower, more solemn pace. I think that this has (or should have) some of the atmosphere of the preparation to the finale in an opera (in the expectation of redemption?). Maybe I just missed some of this operatic aspect? To me, the expressive bass cantilena after the brief ff interjection by the strings confirm this opera aspect.

★★★★

VII. Libera me

Libera me

Here, Corinne Winters’ performance was excellent, expressive, dramatic. I only have very minor reservations towards the end of the solo, where Verdi (almost inhumanly) forces her down to very bottom end of her tonal range.

★★★★

Dies irae

And there it comes again, the Day of Wrath! Here, Gardiner and his team produced at least as much power, force, brutality as in the first instances. Was it slightly faster, or was this mere impression from all the music in-between? The strings could hardly articulate the falling cascades at this pace: Verdi mercilessly writes two notes under a slur and two staccato notes in each group of four semiquavers—this was impossible to hear.

★★★★

Requiem aeternam

The Andante segment, is excruciatingly challenging! Not only is it all a cappella (choir + soprano), but the singers must be exhausted from the performance of around 75 minutes so far, and so the danger of the pitch wandering off is very real. On top of that, most of it is ppp, even ancora più piano, and ending in pppp, and in that final pppp, the soloist much reach up to a B♭. Corinne Winters’ intonation was mostly OK. I again noted a slight tendency towards premature tonal transitions. And in that last B♭, she partly lost control over her voice.

★★★½

Libera me

After a dramatic solo recitative for the soprano, Verdi inserts a dramatic fugue for the choir. Was the Italian pronunciation degrading because the choristers felt the exhaustion, or is it the text Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna that was maybe particularly susceptible to exposing “Englitalian” pronunciation? It wasn’t all that bad, just some of the vowels (“i”, “e”).

It also seemed that Gardiner was pushing forward, denying any broadening at the climax in phrases. Conversely, the sudden broadening in the ppp bars prior to the fermata (bar 311) felt fabricated. I wasn’t entirely happy with the tempo management in most of this final segment. However, the final ppp bars with the senza misura solo offered relief: as if in the end, Verdi’s music took over, a final “let go!”, redemption, at last? — ★★★½