Riccardo Chailly / Lucerne Festival Orchestra

Maurice Ravel

KKL, Lucerne Festival, 2018-08-24

2018-09-31 — Original posting

Verdiente Standing Ovation für Riccardo Chailly, das LFO und Ravel am Lucerne Festival — Zusammenfassung

In einem reinen Ravel-Programm demonstrierte das Lucerne Festival Orchestra Höchstleistungen: perfekte Balance und Dynamik, ein Farbenreichtum sondergleichen, kombiniert mit Riccardo Chaillys untrüglichem Sinn für Temporelationen und dramatische Entwicklungen.

Table of Contents

Introduction

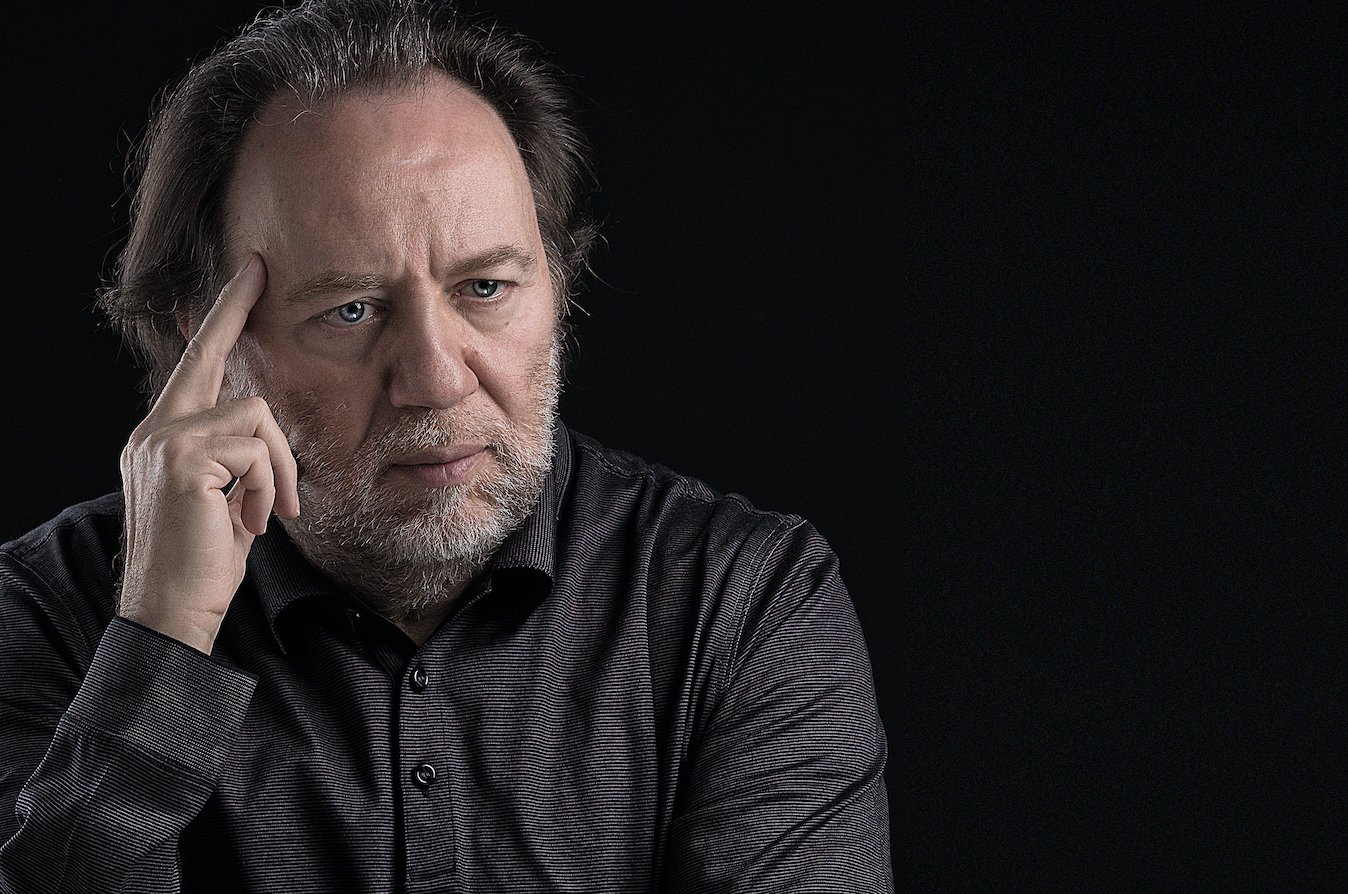

In this year’s Lucerne Festival, Riccardo Chailly (*1953) was conducting four symphonic concerts, all with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra.

Riccardo Chailly in Lucerne

Every year, the festivals turn concert life into a real circus, in which a seemingly endless sequence of top-class artists are parading in front of an exceedingly demanding audience (more demanding than otherwise already).

This concert featured the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, the “house orchestra” of the festival, under its chief conductor, Riccardo Chailly. It’s not one of the world’s most renowned “fixed” orchestras, such as the Berlin or the Vienna Philharmonics. Nevertheless, the podium is full of prominent artists. The string section includes numerous concertmasters, members of famous chamber music formations (such as the Hagen Quartett), and there appears to be the bulk of the Mahler Chamber Orchestra. The latter, as well as the Lucerne Festival Orchestra are prominent legacies created by the late Claudio Abbado (1933 – 2014). With Claudio Abbado’s passing, in 2014, Riccardo Chailly, a former pupil of Abbado, has accepted the position of Chief Conductor of the Lucerne Festival Orchestra.

Challenges for Abbado’s Successor

Sure, Riccardo Chailly knew about the (maybe exceedingly high) challenges of succeeding Claudio Abbado at the head of this orchestra, full of prominent musicians. Under Abbado, the orchestra has grown over years, and to some degree it functioned as a collection of the conductor’s personal friends. With this, I think it is far too early to make any firm assessment about Chailly’s work with the orchestra. Yet, some exponents of Zurich’s local press were recently uttering statements such as “Lucerne has a problem”, or (in essence) “Chailly is a failure for Lucerne”.

Sure, Riccardo Chailly is not Claudio. Actually, it would be a grave mistake to expect the former simply to continue on Abbado’s path. Claudio Abbado was a kind of spiritual magician who (in concerts) seemed to let the music freely evolve in concerts, without much control or direct intervention. Yet, under his hands, a special, unique atmosphere emerged from the spirit of the very moment of creation.

Riccardo Chailly is very different in his work, his actions. He acts (and thinks of himself) as a Maestro. Here, and in general, he was/is conducting accurately, with precision (without being rigid or stiff, of course), keeping the overall control at all times. In this concert, with the complexity of Ravel’s orchestral score, his role was particularly central—so much that the concertmaster merely seemed to fulfill a subordinate function.

However, that does not imply that Chailly sees himself as superhero. Quite to the contrary: he stayed out of the spotlight (literally: the lighting made him appear fairly inconspicuous). He worked with the musicians in the orchestra as colleagues, didn’t try attracting extra attention, and when accepting the applause, he modestly placed himself amongst the musicians at the first desks.

Program

This particular concert was special, in that it was devoted to music by Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937) exclusively. The first part, up to the intermission, combined the Valses nobles et sentimentales and La valse into one piece, giving the former additional weight and meaning, and at the same time, the combination formed a plausible, single, new entity.

After the intermission, the two Fragments symphoniques from Daphnis et Cloé allowed conductor and orchestra to present their abilities, their excellence in performances at the highest level. The final piece was the famous (if not notorious) Boléro, a piece that according to the composer himself “contains no music at all”. That statement may have helped its popularity, and it also promoted some of the clichés around this music. Chailly avoided preconceived ideas. He managed to turn this music into a demonstration of Ravel’s true mastership and subtlety in instrumentation. The program in an overview:

- Valses nobles et sentimentales, for orchestra, M.61

- La Valse, poème choréographique pour orchestre, M.72

— - Daphnis et Chloé, Orchestral Suites Nos.1 & 2, M.57a/b

- Boléro, M.81

Concert & Review

Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales, for orchestra, M.61

Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales, M.61, first appeared in a piano version, in 1911. One year later, 1912, Ravel published an orchestral version. The title originates in the 34 Valses sentimentales, D.779 (op.50, 1825) and the 12 Valses nobles, D.969 (op.77, 1827) by Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828). Ravel did not separate the “noble” and the “sentimental”. Rather, the title of his waltzes suggests pieces that are both noble and sentimental. Ravel’s collection consists of eight waltzes:

- Modéré – très franc

- Assez lent – avec une expression intense

- Modéré

- Assez animé

- Presque lent – dans un sentiment intime

- Vif

- Moins vif

- Épilogue: lent

The composer’s orchestral arrangement asks for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, cor anglais, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, tambourine, cymbals, snare drum, glockenspiel, triangle, bass drum, celesta, 2 harps, and strings.

The Performance

Right with the first of these waltzes, it became obvious that the real focus of the concert was not the conductor, but the composer, Maurice Ravel, and his absolute mastership in instrumentation. Whoever played the original piano version probably almost perished from envy about the subtlety, the richness in details, the abundance of colors in the orchestral version! Chailly combined this with La Valse, which followed almost attacca, see below.

I. Modéré – très franc

So subtle in dynamics and articulation—a performance fully in the service of the music / the composer, not mere show at all! Clarity, both because of Ravel’s transparent orchestral texture, and of course thanks to the discipline in this excellent orchestra.

II. Assez lent – avec une expression intense

Chailly took this a tad on the slow side, maybe. The piano score asks for ♩=104. The waltz was just still recognizable as such, its slow, swaying movement. Very, very careful in articulation and dynamics. Like a gentle sound painting in subtle coloring from the wind instruments—mastership in instrumentation!

III. Modéré

Light, playful, but never superficial, very careful in the agogics.

IV. Assez animé

Here, Ravel’s intent seems to be to defamiliarize the Viennese waltz, through subtle harmonic alienation (supported by Chailly’s intricate agogics!), like a premonition of La valse.

V. Presque lent – dans un sentiment intime

Just as over the entire evening, this was an opportunity to admire the excellent wind soloists in this orchestra! Most amazingly, in the beginning, the clarinetist was able to make his instrument sound so incredibly mellow and soft that I had to look twice whether it was him playing, or rather the flute!

VI. Vif

The Vif movement demonstrated Chailly’s excellent feel for rubato / agogics, but also for the tempo relations between the waltzes.

VII. Moins vif

This is the “core piece” among the eight movements. After a general rest, this waltz starts hesitant, pensive, as if it was holding a secret. Only after another, long general rest, the movement starts picking up momentum. Chailly made this sound like a natural transition, never losing the tension. The waltz rapidly builds up volume, up to a climax, then starts again for a second and third buildup and climax. These culminations very much seem to anticipate the spirit, the atmosphere of La valse. Here it became evident why Chailly was combining these valses with La valse!

VIII. Épilogue: lent

As if waltz No.7 didn’t already anticipate La valse, the performance of the Épilogue made it clear: this must be the transition to the poème choréographique! Chailly managed to keep the tension, the suspense at the highest level, throughout! This slow, reflecting “intermezzo-waltz” was so full of tension, building up expectation with its suspended, floating, restrained atmosphere. La valse absolutely, inevitably had to follow!

Rating: ★★★★½

Ravel: La Valse, poème choréographique pour orchestre, M.72

Ravel composed his “choreographic poem” La Valse in 1920. I have written about an earlier performance of this piece in Zurich, on 2018-06-07. For information on the composition see that earlier post. Before that, (in a private recital on 2016-01-16, and on 2016-04-01 in Baden / CH), I have attended concert performances of La Valse in the version for single piano.

The Performance

A short general rest of a few seconds preceded La valse—seconds in which audience and musicians seemed to hold their breath! Indeed, the combination of the two compositions seemed to be most logical, natural!

Here now, Riccardo Chailly and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra demonstrated their true mastership. No magic (as with Abbado), but conscious phrasing and dynamics, excellent orchestral balance. Yet, the performance never felt intellectual or scholastic, and at no time, the music felt idle or lacking meaning. Rather, Chailly managed to create a compelling dramatic development. The movement starts with seemingly harmless waltz allusions in the bassoons and the horns. However, signs of the impending / evolving cataclysm were present already in the beginning, in the restrained grumbling of the basses.

Only gradually, carefully controlled, Chailly let the music evolve into overexcited episodes, alternating with intermittent, superficially harmless moments. Though, the music was never without that urge in the underground. The latter of course turn more and more volatile, and ultimately, everything gives in to the relentless pull of the absurdity, the pull into the catastrophic ending, in which the music turns into a grimacing caricature. In all this, Chailly retained control, resisted the temptation of exaggerating, overdoing the drama. A masterful performance, both by conductor and orchestra, impressive, insistent, compelling—simply excellent.

Rating: ★★★★★

Ravel: Fragments symphoniques from Daphnis et Chloé, Suites Nos.1 & 2, M.57a/b

Daphnis et Cloé is a ballet in two acts (three parts, the second act is in two parts) that Ravel wrote 1909 – 1912. This is Ravel’s longest orchestral work, with a very rich instrumentation. It features piccolo, 2 flutes, alto flute, 2 oboes, cor anglais, clarinet in E♭, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 French horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, a rich set of percussion instruments, including celesta, 2 harps, strings, and choir. The choir is just singing vocalises (no text). Ravel suggests that it can be substituted for an organ, with support by wind instruments. This was done here. Hence the festive illumination of the instrument.

From the ballet music, Ravel collected three numbers from parts I and II into a Suite No.1 (M.57a), and part III became the Suite No.2 (M.57b). The two suites were performed here like two symphonic movements, the three segments in each of the suites were performed attacca:

- Suite No.1, M.57a

- Nocturne

- Interlude

- Danse guerrière

- Suite No.2, M.57b

- Lever du jour

- Pantomime

- Danse générale

The Performance — Suite No.1, M.57a

I. Nocturne —

Ravel’s dynamic & instrumental disposition is—once more—truly masterful, right from the first tone. As the initial tam-tam beat fades away, its sound is slowly replaced with that of the muted, ppp strings. Into this mysterious sound, the flute starts a free solo, followed by a muted horn, then a clarinet, which leads to a short eruption of sparkling sound magic, into which the wind machine blows a gust of fresh air. The piece lives from a careful dynamic balance, combined with equally diligent management of the rubato and agogics. In Chailly’s hands, this turned into a piece full of suspense and tension. And the atmosphere was truly enchanting!

II. Interlude —

The Interlude, originally for choir, appeared in the orchestral version here. It was all retained, static in a way, yet full of tension & growing expectation. The organ just formed a low-register canvas, on which the woodwinds, then equally excellent brass soloists were drawing in soft, then progressively stronger colors, more and more accentuated (approaching from behind the scene, according to the score). It’s fabulous how the excellent wind soloists evoked a scenery that gets gradually more illuminated, leading into the war dance:

III. Danse guerrière

This third was a fascinating, exemplary demonstration of orchestral excellence, with everybody acting like from one single spirit, one single mind, with a very strong, coherent contribution from the strings. Riccardo Chailly diligently managed the tempo, the musical flow, keeping the tension through a strong, coherent build-up, culminating in a first, vehement climax. That first climax was followed by several more waves, up to the vehement, final clash, all equally enthralling.

The Performance — Suite No.2, M.57b

I. Lever du jour

How excellent Ravel is in depicting nature! Intuitively, I wrote down “murmuring of the water in a brook”. And I found exactly that (in French, of course) as annotation in the score! It’s a truly enchanting scenery, especially, as nature slowly wakes up, with birds singing, sunrise, up to full brightness! This is a very long, slowly evolving build-up. It is particularly demanding, challenging in the orchestral version, without the action of the ballet. Chailly’s discipline and consequence in managing Ravel’s tempo fluctuations, the dynamics, and forming a tension arch was admirable!

II. Pantomime

In the Pantomime, Daphnis and Chloé present the love between Pan and Syrinx. For the most part, this is an extended, highly virtuosic and very expressive flute solo. Jacques Zoon leaves nothing to wish for in this role! I also noted how seamlessly the other flutes joined the soloist towards the end. The transitions from piccolo to the flute, and on to the alto flute were not noticeable at all.

III. Danse générale

The last part was a dramatic, enthralling build-up in waves, up to the fulminant, splashing climax at the end: very effective and impressive. However, in Chailly’s interpretation, this certainly was anything but mere show. It demonstrated the conductor’s feel for dynamic and dramatic development. And it gave testimony of Chailly’s ability to motivate his musicians to deliver a performance at the highest possible level, both technically and musically.

Rating: ★★★★★

Ravel: Boléro, M.81

The (in-)famous Boléro (M.81) requires no introduction. It is so well-known, with its 18 segments on two melodies (9 occurrences each), all in the same tonality, and all accompanied by an ostinato of the Boléro rhythm on snare drum. Ravel himself allegedly stated that “unfortunately, it’s a piece without any music”. This and plenty of anecdotal information is found on Wikipedia. Whether one takes Ravel’s statement for real or not: it’s a fascinating piece. It starts all pp (flute, drum ostinato, pizzicato in the strings), then gradually builds up in colors, volume and complexity of the instrumentation, up to a 5-bar finale, modulating through dissonances to the final C major chord.

The Performance

In pre-concert announcements, Chailly stated that he intended to stick to Ravel’s exact tempo (♩=72)—and he did! Initially, there appeared to be a slight unrest in the pace. However, this was merely a question of adaptation on the listener’s side. Not unlikely, it could be the memory of performances that start the piece a tad slow(er), lyrically broadened, then unnoticeably accelerating towards the end. This of course would have been against the composer’s intent. Chailly resisted such temptations. He indeed kept the tempo consequently and throughout the piece.

In lieu of evolutions in the tempo, in Chailly’s hands, we could observe the miracle of gradually developing orchestral coloring. It was marvelous to observe how the wind instruments mutually adopted their colors, letting the soundscape change and evolve seamlessly. In this, perfect dynamic control was absolutely instrumental. For quite a while, the ostinato of the Boléro rhythm on the snare drum remained almost absent. It seemed merely a component in the underground. Only over time, it gained stronger presence, as if it was dragged along by the relentless, dynamic & dramatic pull towards the final climax. That pull was a build-up that seemed to take hold of every single musician in the orchestra. Fascinating!

Rating: ★★★★★

Deservedly, orchestra and conductor received a spontaneous, standing ovation. Congratulations for an overwhelming demonstration of orchestral excellence!

Addendum

For this concert I have also written a (shorter) review in German for Bachtrack.com. This posting is not a translation of the Bachtrack review, the rights of which remain with Bachtrack.com. I created the German review using a subset of the notes taken during this concert. I wanted to enable my non-German speaking readers to read about my concert experience as well. Therefore, I have taken my original notes as a loose basis for this separate posting. I’m including additional material that is not present in the Bachtrack review.