Antonini, Tonhalle Orchestra, Zürcher Sing-Akademie

Schubert: Symphony No.4, Mass in A♭ major

Tonhalle Maag, Zurich, 2017-11-03

2017-11-07 — Original posting

Guiovanni Antonini mit der Vierten Sinfonie und der Fünften Messe von Schubert — Zusammenfassung

Das Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich unter Giovanni Antonini bot durchweg ausgezeichnete Interpretationen—historisch informiert in Gestaltung und Phrasierung, doch nicht so provokant radikal wie etwa Harnoncourt.

Nicht nur die Aufführung “Tragischen” Sinfonie, auch die der Messe war ausgezeichnet. Leider standen die Vokalsolisten unmittelbar vor dem Chor statt neben dem Dirigenten, wodurch sie sich von den Sängern der Zürcher Sing-Akademie zu wenig abhoben, sich zu wenig profilieren konnten. Nach etwas Anlaufschwierigkeiten im Kyrie (Gewöhnung an die Akustik?) erfüllten die 35 Sängerinnen und Sänger des Chores die in sie gesteckten, hohen Erwartungen voll und ganz.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Another concert in the newly built Tonhalle Maag in Zurich, with the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, which calls this venue its temporary home for the coming three years. But even though my first concert visit in this venue on 2017-10-18 was with the same orchestra, it’s not a repeat experience: for one, this was a private visit (not through / for Bachtrack), so I did not have one of the typical “reviewer seats” in the middle of the hall, but rather chose to sit in the middle of the last row (#23) of the parquet seating. Then, after the intermission, this was a concert with choir and vocal soloists, hence another (personal) test for the acoustics.

Setup, View

Before I turn to the actual event, let me insert one remark about the venue. It looks bright, it looks wide (some extra height would not hurt, I guess).Judging from past concerts, the acoustics are very good, even though lacking reverberation. One disadvantage my wife and I noted is that the podium, at a height of around 1 – 1.2 m in the front, is relatively flat, ascending only at the very rear end. With this, listeners in the parquet seats (i.e., the majority of the audience) have a rather limited view onto the orchestra, in particular onto the woodwinds, given that the parquet is entirely flat. This issue may have been worse in this concert, as the ascending part of the podium was largely occupied by the choir. Next time when I select a seat myself, I may actually select a seat on the rear balcony.

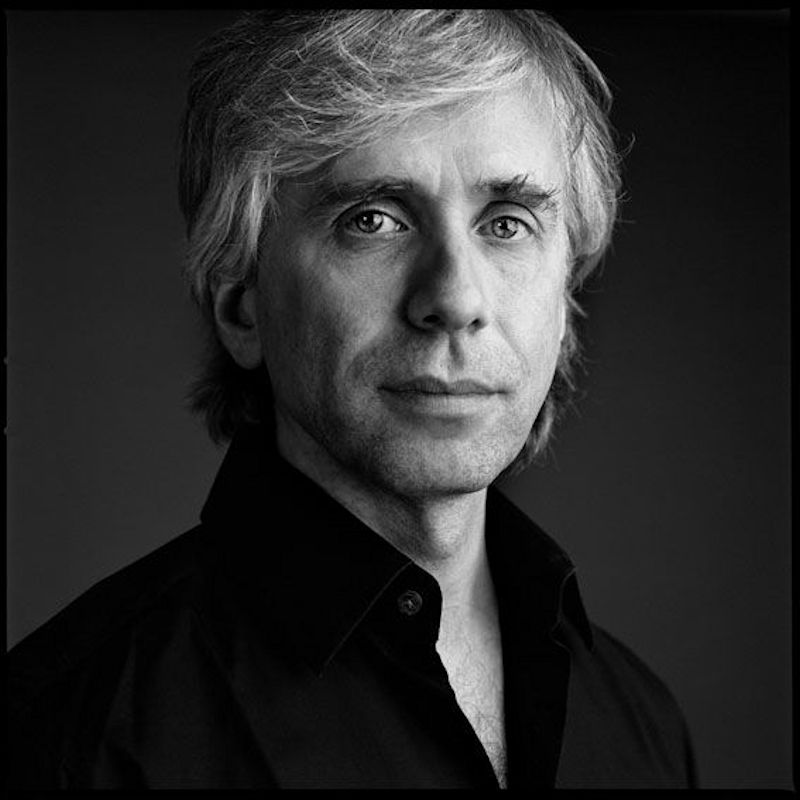

Giovanni Antonini, Tonhalle Orchestra

In this concert, Giovanni Antonini (*1965) conducted the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich. With the repertoire in this concert, the orchestra was present in a reduced size, I counted 10 + 8 violins, 6 violas, 4 cellos, 3 double basses. It’s not the first time that Giovanni Antonini is conducting in Zurich: after a first appearance with his own orchestra, the baroque formation Il Giardino Armonico, back in 1994, he has conducted the Tonhalle Orchestra already 10 years ago. His most recent cooperation with the orchestra was this summer, in a concert in the “old” Tonhalle on 2017-07-05. He is principal Guest Conductor with the Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg, as well as with the Kammerorchester Basel.

Schubert: Symphony No.4 in C minor, D.417, “Tragic”

Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) wrote his Symphony No.4 in C minor, D.417, in April 1816 (he was only 19 then!). Schubert added the by-name “Tragic” to the manuscript some time after the completion. It is one of only two symphonies in a minor key. However, its character is not really that tragic—at least, not throughout. The work features the following four movements:

- Adagio molto (3/4) – Allegro vivace (4/4)

- Andante (2/4)

- Menuetto: Allegro vivace (3/4) – Trio (3/4)

- Allegro (2/2)

The public premiere of the symphony took place in 1869 only—long after the composer’s death.

The Performance

Throughout the evening, Giovanni Antonini was conducting without baton, with large, expressive / emphatic, usually “upbeat” gestures, often symmetric, and with a lively body language. Visually, his gestures seemed to indicate portato articulation.

I. Adagio molto – Allegro vivace

In the slow introduction, mellow portato articulation dominated: at this tempo, the staccato dots almost appeared as broad non-legato. It was clear immediately that Antonini carefully followed Schubert’s notation in articulation and dynamics. He did not over-dramatize the music, though: the atmosphere was earnest, serious, but not rebelling or revolutionary in any way.

The Allegro vivace part confirmed this impression: a fluent, still natural tempo, not pushed / overly driven. Antonini was very careful in articulation and phrasing (clearly and consistently separating the phrases by relieving the last notes), direct in the expression, but not loaded with pathos, clear. Antonini was not trying to provoke or over-emphasize. In that respect, he differs from HIP pioneers such as Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1929 – 2016). Of course, Antonini repeated the exposition , and even though the second pass was pretty much identical to the first one, the music never felt boring, retained its tension from beginning to end.

Interesting: the switch to a much faster (Presto) tempo in bar 269. That’s something also Harnoncourt was propagating in his recordings (no indications to that effect in the score).

Within the orchestra sound I liked the clear presence of the wind instruments, thanks to the small string body and the excellent, clear and analytical acoustics. Overall, the movement clearly exhibited classic form and proportions, classic serenity, not Sturm und Drang, not the emotional turmoil of Schubert’s late works, nor early romantic expressiveness.

II. Andante

Here, Antonini was considerate, careful in the tempo, emphasizing the Lied character of the movement. Andante could also be taken for a substantially more fluent tempo. Here, it almost felt like an Adagio. In Antonini’s hands, this was serene music, resting (not boring, though) never driven, expressive, careful and eloquent in the articulation.

The “B” part appeared with clearly more earnest, tragic atmosphere, with an expressive exchange if sighing motifs between violins and wind instruments (flute & clarinets). The B part is episodic, as the music returns to the serene, slightly melancholic, longing mood (so typical for Schubert) of the “A” part.

III. Menuetto: Allegro vivace – Trio

Schubert notated this in 3/4 time, though the syncopes consequently avoid any “Menuetto dance swing”. At the same time, the “hemiolic feeling” through the slurs (crotchets in pairs) further obscures the 3/4 meter. In this interpretation, the title Menuetto certainly was misleading: Antonini (correctly) focused on the Allegro vivace annotation, took the music in entire bars: not a Menuetto, rather a Scherzo (a bit too grim to be joking, though). To me, the interpretation felt classic, not excessively tragic or rebelling.

In the mostly earnest context of the “Menuetto“, the Trio is serene, melodic episode. Now, here, there was the “3/4 Menuetto character”—once more classic, fluent, never overly expressive or melancholic.

IV. Allegro

In this interpretation, the final movement presented itself as one of Schubert’s true masterworks: enthralling, electrifying, virtuosic, keeping its tension throughout! With all the tremoli and the fast, repeated motifs, the music feels as busy as many of Mendelssohn’s compositions. And the performance! It showed the Tonhalle Orchestra at its best: virtuosic, clear, precise in coordination, light in articulation, lively in the dynamics, both playful and dramatic. Giovanni Antonini ensured that tension and drive never weakened!

The development section starts with low tremoli in the strings. Here, this created an atmosphere like at the end of the overture to an opera. Then, the music seems to ease up, turning more melodic. However, that is just the introduction to the short, but dramatic development part with which the music relentlessly pulls into the recapitulation section and into the Coda. Antonini lets the symphony end resolutely, with three affirmative, compact, full-bar chords. These were slightly slower than the coda, but without prior rallentando.

With almost 34 minutes, this was a short first half of the concert. Could this have been the reason for the fair number of empty seats? Or was this rather because the repertoire was “just” Schubert?

Schubert: Mass No.5 in A♭ major, D.678, “Missa solemnis”

Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) composed a first version of the Mass No.5 in A♭ major, D.678, “Missa solemnis”, between 1819 and 1822. It’s the only one of his mass compositions that was not written for a specific (known) event / occasion. The work premiered with Schubert’s brother Ferdinand Schubert (1794 – 1859) conducting. The composer apparently was not satisfied with the Mass. Therefore, in 1826, he created a revised version, which he held in high esteem. Sadly, after a performance in Vienna, the Emperor found it to be too long and too “difficult”, so the score was returned to the composer. It was up to Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897) to take this composition up again, performing it in 1874 in Vienna. Before that, individual movements had been performed in Leipzig, 1863.

Structure

The mass follows the ordinary liturgic structure:

- Kyrie: Andante con moto (2/2)

- Gloria: Allegro maestoso e vivace (3/4) —

Gratias agimus tibi: Andantino (2/4) — Domine Deus, Rex coelestis — Gratias agimus tibi —

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei: Allegro moderato (2/2) - Credo: Allegro maestoso e vivace (2/2) —

Et incarnatus est: Grave (3/2) —

Et resurrexit: Allegro maestoso e vivace (2/2) - Sanctus: Andante (12/8) —

Osanna in excelsis: Allegro (6/8) - Benedictus: Andante con moto (2/2) —

Osanna in excelsis: Allegro (6/8) - Agnus Dei: Adagio (3/4) —

Dona nobis pacem: Allegretto (2/2)

Missa solemnis?

Just a short clarification: “Missa solemnis” is not (necessarily) a reference to the famous Missa solemnis in D major, op.123, by Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827). It simply means “solemn Mass”. This is a festive Mass, typically rich in instrumentation, in which the composer does or may not just follow the Roman-Catholic Mass ordinary (ordinarium) straight through, but may repeat sections, as it suits the purpose of the composition. The antonym to Missa solemnis is “Missa brevis” (short Mass), which is a (more modest) musical setting of a straight reading of the Mass ordinary.

The Singers

After the intermission, the Zürcher Sing-Akademie (SATB, 10 + 9 + 8 + 8 singers) occupied the rear part of the stage, in three rows. In the front two rows, they left a gap in the center, for the soloists. I have heard this choir in several concerts. It clearly is at the forefront of all choirs in Switzerland—maybe the best of them. The choir was founded 2011 by Timothy Brown (*1946), who led the ensemble till 2015, then ad interim by Andreas Felber (*1983). Starting this season, the choir master is Florian Helgath (*1978). Since 2011, Helgath has been leading the ChorWerk Ruhr, one of the leading chamber choirs in Germany, located in Essen.

Soloists

The program listed four soloists, none of which so far have performed with the Tonhalle Orchestra. Among these, the soprano Katja Stuber unfortunately fell ill. In her place, the experienced soprano Sibylla Rubens stepped in. Next to her sang the mezzo-soprano Olivia Vermeulen. On the right side, we saw the tenor Martin Mitterrutzner, and the bass Tobias Berndt.

The Performance

Naturally, after the intermission, my focus was on the Zürcher Sing-Akademie and the vocal soloists—and on their “interaction” with the acoustics of the venue.

I. Kyrie

After 8 introductory orchestral bars, all p and pp, the female voices of the choir sing the first Kyrie eleison, then only the male voices set in.

It is a very exposed beginning for the choir. Maybe the choristers felt a little bit insecure initially? They are professional singers, though, and they had been singing Beethoven’s Ninth at the venue opening. However that is less critical for the choir. In any case, in this beginning, I was slightly disappointed by the choir, as it felt somewhat inhomogeneous, or at least not as homogeneous, especially in the female voices, as I had expected. But I was pleased to hear that in the pp ending of the first Kyrie, the choir had “found its shape”, producing a wonderfully sonorous, well-projecting decrescendo into an impressive pp.

Choir Acoustics?

Sure, the acoustics in this venue are very analytical and transparent. I suspect that the acoustics are also far more “open” than in the old Tonhalle, i.e., lacking direction / projection. It turned out that after the Kyrie, the choir was actually more than just OK—it performed up to my expectations. Hence, I would book this under “starting problems”. On the other hand, I could very well imagine that with its transparency and clarity, this venue is far more critical for lay choirs than venues in which these have performed in the past, such as the old Tonhalle.

Christe eleison / Soloists

In the Christe eleison, I wasn’t entirely happy with the vocal soloists either. For one, I found Sibylla Rubens‘ vibrato too heavy, too dramatic, too strong—stronger than with the other soloists. Bus as she was a short-term replacement, I can of course not blame the organizers for not having selected a voice that better fits the other soloists.

None of the soloists actually sounded quite as impressive as I had hoped. I think that it would have been much better (for this venue, at least) if the soloists had been sitting next to Giovanni Antonini, in front (or within the half-circle) of the orchestra. The issue may have been compounded through the combination with a professional choir, which reduces the difference in voice quality and volume between soloists and choir.

Over the entire Mass, though, I got used to Sibyilla Rubens’ soprano. I partially revised my objections about her vibrato. The voice I liked most was Olivia Vermeulen‘s alto, followed by Tobias Berndt‘s bass (even though he was sometimes hard to hear when the choir was singing as well). Martin Mitterrutzner‘s tenor voice seemed the smallest one in volume (in the Christe eleison). However, my relative rating may have been influenced by the placement of the soloists behind the orchestra. I had the feeling that the acoustics turned out more favorable for the female voices (choir and soloists).

Interestingly, this mass features two “Christe eleison” episodes.

II. Gloria

The beginning of the Gloria instantly changed the previous impression about the choir. Now, the singers performed up to my expectations: expressive, vivid, with impressive power and volume, excellent in diction and articulation. The solo quartet appeared embedded in the sound, though—as mentioned above—the tenor, and primarily the bass (often hard to hear at all) appeared to fight an acoustic adversity.

Gratias agimus tibi

This presents the four soloists: the soprano was OK, albeit somewhat dominating.

Domine Deus, Rex coelestis — Gratias agimus tibi — Domine Deus, Agnus Dei

Up to the Miserere nobis: here, mezzo-soprano, tenor and bass had a chance to present their voices. And each voice, taken by itself, was definitely good in volume, timbre. I can’t complain at all. So, my quibbles really refer to the quartet balance, and to the quartet as embedded in the sound of choir and orchestra, see above.

Quoniam tu solus sanctus

With the Quoniam, the focus returned to the choir, which started that second major part of the Gloria with a very impressive crescendo, fired up by Giovanni Antonini’s wide-spanning, imaginative gestures, his suggestive conducting. The singing of the choir was full of oratorio-like drama, power and force, expressive in dynamics. Maybe occasionally it was a bit on the strong side with the sforzati (fz). But in parts, this is inherent with Schubert’s score (I’m thinking of the altissimus segment).

Cum sancto Spitiru

With its impressive polyphony, the last part of the Gloria definitely takes us into the world of Haydn’s oratorios: an impressive choral composition, a polyphonic masterwork that Schubert must have been proud of! And of course, the choir totally lived up to the level, the quality and richness of Schubert’s composition: impressive, heart-warming, sending chills down through the spine!

III. Credo

After the two introductory chords in the wind instruments, the choir impressed with two a cappella segments with excellent sonority also at mf level, careful dynamics, very good diction and articulation: fantastic! The choir has plenty of volume that easily withstands the ff interjections by the orchestra. At the end of this segment, the choir retracts into a pp—without giving up any sonority and homogeneity, preparing for the mystery of the incarnation:

Et incarnatus est

Excellent sonority also in the trombones, with perfectly smooth tone. Schubert keeps this choir segment recitativic, not bound to a theme or a melody. Stark dynamic contrasts, dramatic musical gestures, a somber soundscape in minor tonality indicate the seriousness if the Crucifixus.

Et resurrexit

The return of the initial fanfares indicate the resurrection—but not with a splash, rather with a long crescendo, leading into dramatic, expressive exclamations, fired up by theatrical gestures by Giovanni Antonini. I also found the mystery atmosphere in the Confiteor very well done, with excellent sonority in the choir, all at pp level. Of course, the Credo has a jubilant ending, into which the solo quartet joined in—without “acoustic issues”, as the solo parts alternate with the choir.

IV. Sanctus

The Sanctus is dramatic not only in its initial build-ups, but also in Schubert’s amazing modulations. The initial segment contains some tricky beginnings for the brass section—mastered flawlessly by the orchestra, of course. Some of these reminded me of the Aequales for trombones by Anton Bruckner (1824 – 1897). And the movement is another opportunity for the Zürcher Sing-Akademie to demonstrate its big choir sound.

Pleni sunt coeli — Osanna

I found the otherworldly, iridescent atmosphere in the Pleni sunt coeli et terra fascinating. Schubert presumably wanted to express the mysteries of the world beyond. The Sanctus closes with the very short, jolly, almost joyfully jumping, dancing Osanna: a little too happily dancing, maybe?

V. Benedictus

The pizzicato accompaniment to the opening solo trio (SAT) let the soloists demonstrate excellent ensemble qualities, without the need to fight for acoustic presence. Quite adequately, Schubert switches to staccato accompaniment for the choir segments—and also this of course minimizes the effort for the choir singers in demonstrating their outstanding vocal qualities.

VI. Agnus Dei

Again, I felt that the soloists deserved singing from the front of the podium, which would have given them better presence, better contact with the audience. The exception to this may have been the soprano, which—through Schubert’s disposition and/or the characteristics / acoustics of the venue—seemed to have the least amount of challenge in maintaining vocal presence. Here, the choir impressed less with volume than with excellent sonority in the p – mf range and mezza voce singing.

Dona nobis pacem

After the prayer-like calmness of the Agnus Dei, the strings remove the mutes, the mood brightens up for the Allegretto of the closing Dona nobis pacem. The music switches between the solo quartet and exclamations by the choir , accompanied by festive ff fanfares by the orchestra, and with tonality changes so typical of Schubert. The end, however, is pp, unexpectedly short, with two brief crescendo-decrescendo swellings, switching to a reflective mood in the very last moment.

Conclusion

Overall, I found that this concert offered excellent performances almost throughout. I liked the symphony, and I liked almost all of the Mass. The “initial flaw” in the Kyrie may have been a mishap. It may also indicate the choir took that section too lightly? On the other hand, the Kyrie made me suspect that the acoustics might prove challenging for lay choirs. And: with the open acoustics in the hall, I think it is easier for vocal soloists to reach out to the audience if they are singing from the front of the podium.